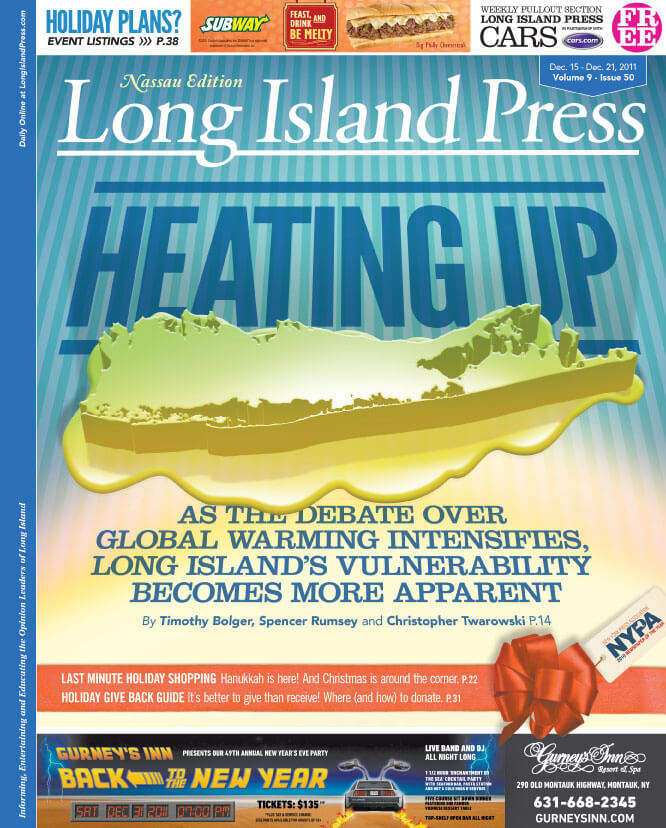

HEATING UP

Global warming’s impact on Long Island and the surrounding region is well documented. Climatologists have reported an increase in average temperatures of more than 1.5 degrees in the Northeast since 1970. Of course, climate change isn’t only about the mercury rising.

A recent federal study found a 67-percent increase in heavy downpours in the Northeast through the past four decades as well. While the increasing number of resulting beach closures due to post-storm bacteria-level spikes is troubling to the local economy, it is the combination of the warming, increasing storms and rising sea levels that adds up to widespread trouble—ramifications, say local environmentalists, that are already evident across Long Island.

“Low-lying areas are more frequently flooded, such as areas including Lindenhurst, Mastic and Shirley, Baldwin, a number of areas on the South Shore,” explains Esposito. “We’ve also experienced loss of wetlands because of increase in tides and increase in water levels. When there’s less wetlands, we diminish the Island’s ability to prevent the flooding of the mainland.”

In addition, Esposito says Long Island has also been victim to more frequent “flash-flood rain events,” which overwhelm sewer systems and push Nassau’s troubled sewage treatment plants even further to the brink. The double knockout punch of Hurricane Irene in August and a torrential storm the weekend prior “caused five of our sewer systems throughout Long Island to overflow and release partially or untreated sewage,” she says: Nassau County’s Bay Park and Glen Cove sewage plants, along with those in Long Beach, Lawrence and Baldwin.

“Raw sewage floated down the streets in Baldwin,” she continues. “[It] actually cracked the pavement as it came up through the storm sewers, which were bolted down, went into people’s homes and into their basements. This wasn’t even reported on… They never notified the public.

“It overwhelms sewage treatment plants, it overwhelms recharge basins, storm filtration devices,” she adds. “We are not built for this type of torrential rainfall, which is causing infrastructure problems for roads and sewage treatment plants.

Esposito echoes the concerns of a 2010 New York State Sea Level Rise Task Force report, which, among other findings, discussed that rising ocean levels will not only be a problem for those who can afford oceanfront property—but anyone who drinks from Long Island’s underground aquifers. The disastrous possibility of saltwater intrusion of Long Island’s underground drinking water aquifers—something she says Port Washington and the North and South Forks are especially susceptible for due to rising sea levels—is something Kramer has been involved with raising awareness about since the 1960s.

“There is a large saltwater wedge in both the Magothy—the main drinking water supply of Nassau County [which also lies beneath Suffolk]—and the Lloyd Aquifer, the main drinking water supply of Long Beach island, and it will further infiltrate that,” he explains. “As sea level rises—and it’s believed that it’s accelerating—it’s going to further cause problems.”

“We’re not one of the fortunate recipients of a giant pipe of water coming down from the Adirondacks,” Ellen Mecray, the Bohemia-based regional climate services director for NOAA, says of the impending threat of saltwater intrusion in LI aquifers.

She confirms extreme weather in the past year is evidence of climate-change and describes coastal erosion as a result of seal-level rise as the top concern.

Lisa Schary—who along with her husband Rich steward the 423-acre Massapequa Preserve—emphasizes global warming’s effects on wildlife and marine animals, pointing to more and more dolphins and seals washing up along Long Island’s shores.

Then there are the hurricanes, warns Kramer, the Scharys and Scott Mandia, a professor of physical sciences at Suffolk County Community College who points to preparations the business world has made to compensate for the trend.

“Insurance companies see the writing on the wall, they know we’re overdue for a major hurricane,” he explains. “Your deductable does not apply [to hurricane damage]. Climate change was definitely a factor in that.”

Fresh off Hurricane Irene, which was considered a major hurricane when it reached Category 3 status with 120 mph winds in the Bahamas, some may question that LI is still overdue. But that storm slowed to a Category 1 when it first hit North Carolina and was a tropical storm by the time it made landfall in Brooklyn on Aug. 28. For us, the so-called “storm of the century” remains the 1938 Long Island Express, which was a Category 3 when it rolled ashore here.

Mandia says evidence shows hurricanes will increase in intensity due to global warming, becoming more volatile and intense as the world’s oceans heat up. When—not if—The Big One finally arrives, LI will not “dodge a bullet,” he adds, as so many suggested the region did after Irene. But he describes stronger hurricanes are just an “extra log on the fire” of the combined consequences bearing down on the region.

As the air and sea water heat up, more violent and powerful hurricanes become greater possibilities, says Mandia, and to Long Island, which has been built up considerably—especially the waterfront communities—since 1938, the damage and loss of life could be catastrophic.

“As you’re seeing all across the country, and various parts of the world, as the climate either warms or cools, the nature of storms becomes more frequent and more severe,” says Kramer. “So we’re going to be getting that.

“It would be incredible damage,” says Kramer, adding that “the city of Long Beach committed physical and economic suicide in 2006 when they rejected an [U.S.] Army Corps of Engineers storm-reduction plan that would have built a large dune the length of Long Beach and connected with the dunes at Lido, which would have given tremendous protection against most hurricanes.”

Rich Schary notes that our location at a 90-degree angle doesn’t help.

“We’re right in the bull’s eye,” he says. “Global warming increases this chance.”

Researchers who worked on the sea-level report suggested ocean levels could rise from nearly two feet to more than four feet in the next 70 years, with the second figure based on a scenario in which there is rapid ice-melt in the arctic regions.

Another even more alarming and more recent report, titled Global Sea Level Linked to Global Temperature and published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in June, finds the rate of sea level rise along the U.S. Atlantic coast is greater now than at any time in the past 2,000 years—and has shown a consistent link between changes in global mean surface temperature and sea level.

Regardless of the rate of sea rise, much of the four barrier beaches south of LI would likely be under water and homeowners in low-lying coastal areas on the South Shore and East End might come to inherit the pricey oceanfront views, if they don’t get washed away too.

This scenario is detailed within the public-benefit corporation New York State Energy Research and Development Authority’s Responding to Climate Change in New York State: The ClimAID Integrated Assessment for Effective Climate Change Adaptation published last month. The 60-page report, authored by more than two dozen academics from Columbia University, Cornell and The City University of New York, paints a frightening portrait of the Earth throughout the next century.