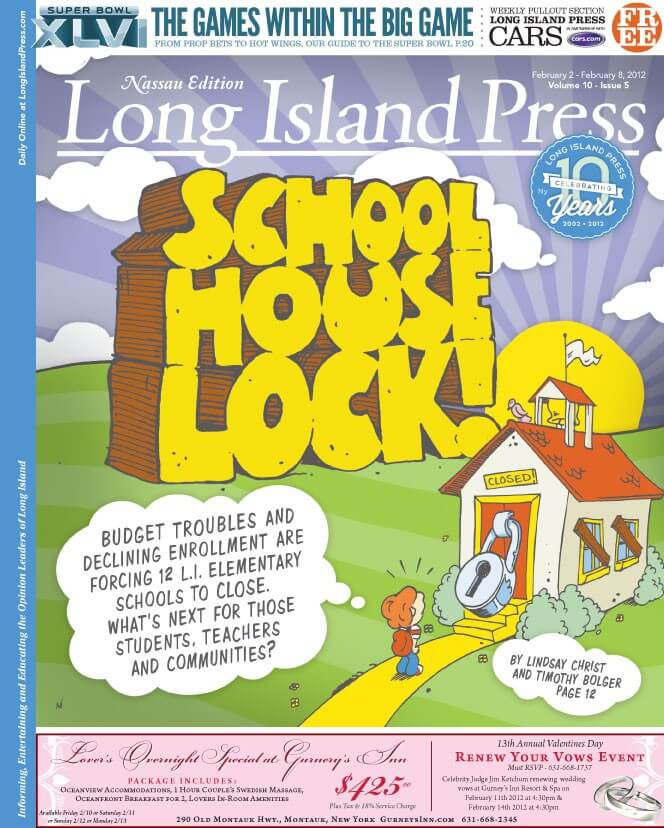

No Recess

When Gov. Andrew Cuomo made his second budget address last month, his proposal to tie $250 million of $805 million in new school aid to competitive performance-based grants set off the annual tradition of school leaders and constituents flooding lawmakers with pleas to increase proposed funding. To this crowd, his vow to be a “lobbyist for the students” fell on deaf ears.

Schools were already reeling from years of aid cuts when the governor won his freshman effort last year to pass the 2-percent cap, which limits how school districts and other local governments raise property taxes. Just like the many districts that are planning to compensate by trimming staff and programs, the public schools facing closure blame the state’s budgetary one-two punch.

“There’s a fine line between being efficient and tightening your belt in a time of diminishing resources, and taking action that harms children and harms student programs,” says Carl Korn, spokesman for the New York State United Teachers union, among those leading the school funding fight in Albany.

“It’s particularly acute on Long Island, which is known for the high quality of its public schools,” he adds. “That excellence that Long Island schools are known for are being jeopardized by three consecutive years of cuts and a tax cap.”

Those tasked with compensating for the funding cuts say they’re doing their best to ensure that the quality of education isn’t sacrificed by the impending school closures. Students will just have to endure a longer bus ride, learn a new building and meet new classmates and teachers.

“State aid has been flat. We’re losing federal aid, [and] we had been getting up to $1 million a couple of years ago. Last year I had $400,000, this year nothing,” says Arnold Goldstein, superintendent of North Bellmore Public Schools, who adds that rising expenses—especially in pension payments—add fuel to the fire. Regardless, he realizes closing schools is not a popular decision.

“Most people aren’t happy about it—I’m certainly not happy about it—the board is not happy about it. But these are the circumstances that we face, and we have to deal with them without hurting kids,” he continues. “The money’s just not there.”

The move is expected to save North Bellmore nearly $1 million. Some teachers will be transferred to the other schools along with the 238 students, Goldstein says.

These numbers are on par with other districts: West Islip (transferring nearly 700 students and up to $3.2 million in expected savings between their two schools), Smithtown (342 students for nearly $1 million), and Baldwin (up to 299 students for up to $1.3 million). Like North Bellmore, each one tasked a committee made up of PTA leaders and other concerned parties to study the school closure proposal and give their suggestions to their boards of education for final approval.

“There are really very few people in the general public who are familiar with how difficult this is,” said Edward Ehmann, superintendent of the Smithtown Central School District, to the Citizens’ Advisory Committee on Instruction and Housing on Jan. 26 as they finalized their report on the proposal to close Nesconset. “You’ve taken the criticism of the process out of the equation.”

That may be wishful thinking, however, if the rising waves of parents’ and teachers’ recent protests are any indication. Gunther parent Bove contends that North Bellmore school officials rigged his district’s citizens’ panel by providing faulty numbers.

“They wanted them to reach this conclusion,” he says, speculating that new housing developments nearby and Catholic schools’ closing could mean a rebound in student population. “All the data was manipulated.”

But school district officials say they study the population trends closely. Experts say Long Island is in the midst of a five-year trend of a 6.2-percent decrease in school-age population—a drop of more than 31,000 students, equivalent to the student population of about 18 high schools—according to 2010 data compiled by St. John’s University Oakdale-based Center for Educational Leadership and Accountability.

With fewer younger families moving in to chase the white-picket fence dream of raising children in the suburbs, the budget problems are made worse because there are now fewer kids to send to school. Eroding the tax base by the increasing number of vacant homes and businesses doesn’t help, either.

“Homes are not selling or turning over, so you don’t have young families coming in and older families leaving at the rate that they used to,” explains Richard Simon, superintendent of West Islip Public Schools. “We needed to look at the fact that many of the buildings are not being used to their full capacity or even close to their full capacity, so we have a responsibility to say, ‘We are going to operate our schools in the most cost-efficient way.’”

At least the public schools have taxpayer support. Their private school colleagues face the same population trends, with fewer families able to afford tuition and only private fund-raising to help fill the growing gap.