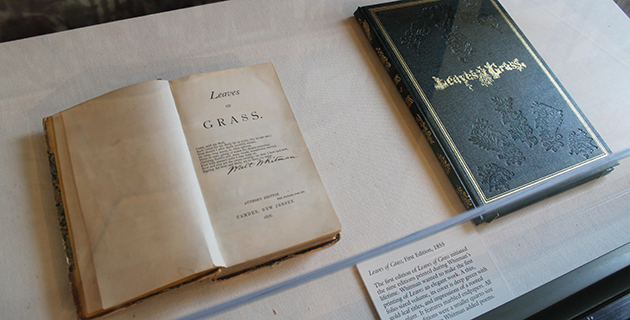

America’s pioneering poet, Walt Whitman, was born in 1819 on his family’s Suffolk County farm in a house built by his father that still stands in West Hills. Of course, the once fertile fields and thick forests that made such an indelible impression on his creativity as he wandered and wondered about have much diminished—but their influence comes through just as strong today as when he first published his seminal work, Leaves of Grass, in 1855.

When he was 4, he and his family moved to Brooklyn, but he came back many times over the years: as a teacher, a newspaper publisher and an accomplished wordsmith. The last time Whitman visited his homestead, The Good Grey Poet, as he’d later become known, was 62. Now the quaint two-storied shingled house is run by the Walt Whitman Birthplace Association, a nonprofit group, which arose in 1947 when the site was in the way of the newly planned Route 110. Instead, the highway was moved and Whitman’s homestead was preserved for future generations.

These days the association is engaged in the long process of applying for National Historic Landmark Status, which would give it greater recognition. This status has already been granted to Whitman’s home in Camden, N.J., the only place he ever owned, where he spent the last years of his life, dying in squalor crippled and broke in 1892 after publishing O Captain! My Captain! and Drum-Taps, among his iconic poems and collections on the Civil War.

Cynthia Shor, the executive director of the Walt Whitman Birthplace Association, is hopeful about their prospects for the West Hills home.

“We are making the case—which we certainly believe—that the environment really imprinted him, and really created the young spirit and soul that was Whitman,” she tells the Press. “He revered nature. He wrote three poems that specifically talked about his birth and early childhood. One of them was ‘When a Child Went Forth.’ It’s a list poem: He becomes the birds, he becomes the land, and he becomes the daffodils, so to speak. We infer that he’s telling us that the home of his birth imprinted him mentally, spiritually and characteristically.”

That influence is clear to Karen Karbiener, a Whitman scholar at New York University who is working on a book titled Walt Whitman and New York, and is an honorary board member of the birthplace association.

That influence is clear to Karen Karbiener, a Whitman scholar at New York University who is working on a book titled Walt Whitman and New York, and is an honorary board member of the birthplace association.

“Long Island was Whitman’s America in his youth and, to a great extent, through the creation of the first three editions of Leaves of Grass,” she says. “He knew this region like no other.”

It was here, she observes, that he founded Huntington’s newspaper, The Long-Islander, which was bought last month by Huntington businessman James Kelly. He also became interested in politics as an electioneer for Martin Van Buren’s campaign and published his first poem, “Young Grimes,” in the Long Island Democrat on Jan. 1, 1840. From Whitman’s autobiographical work, Specimen Days, he wrote that “the successive growth stages of my infancy, childhood, youth and manhood were all pass’d on Long Island, which I sometimes feel as if I had incorporated.”

According to Pulitzer Prize-winning biographer Justin Kaplan, no bylined articles have been found from Whitman’s tenure at his own paper, which he sold after a year because, as he put it, “only my own restlessness prevented me gradually establishing a permanent property there.” But two articles he wrote for the Democrat, which was based in Jamaica, Queens, do survive. One was about “an unfortunate and somewhat singular accident” in July 1838 when a Northport farmer carrying a pitchfork on his way home from his fields was struck by lightning that “killed him on the instant.”

Today, Whitman is remembered not for his journalism or his time in the classroom, which he by his own words detested. As was common back then, a teacher in LI’s rural communities would board with the parents of his students and handle a schoolhouse of up to 80 kids ranging in age from 5 to 15 for nine hours a day.

In a letter written in 1840 to his friend Abraham Leech, Whitman denounced Woodbury, one of the places he taught, as a “Devil’s den” and “Purgatory Fields,” adding that “when the Lord created the world, he used up all the good stuff, and was forced to form Woodbury and its denizens out of the fag ends, the scrapts and refuse… [I]gnorance, vulgarity, rudeness, conceit, and dullness are the reigning gods of this deuced sink of despair…[h]ere in this nest of bears, this forsaken of all God’s creation; among clowns and country bumpkins, flat-heads, and coarse brown-faced girls, dirty, ill-favoured young brats, with squalling throats and crude manners…”

Those words would hardly describe the generation of kids who’ve taken class trips to the birthplace since its opening. Curators have done their best to recreate what his home looked like in the 19th century when he lived there and convey his importance to American culture. But it was never an easy task in the group’s beginning, given the birthplace’s close confines.

“School children would come into the house and they would sit on the floor and I would teach them poetry,” recalls Shor. “That was always a delight. And when it was over, I’d hop behind the counter and sell them candy bars to make money for the birthplace.”

A visitors’ center was built in 1997 to accommodate class trips, lectures, poetry workshops and showcase Whitman memorabilia, such as a recording the poet made for Thomas Edison, as well as provide offices for the association’s staff. The house itself underwent a much-needed restoration in 2001. In recent years, a larger-than-life-sized bronze statue of the poet holding a butterfly was donated to the site and now stands within its courtyard. People from across the country and the globe visit the humble bedroom at the back of Whitman’s brown-shingled home where the famous poet entered into this world.

The Walt Whitman Mall, owned by Simon Properties, is less than a football field away from the birthplace. Perhaps the only mall in America named after a poet, the façade facing the parking lot once had excerpts from Leaves of Grass emblazoned on its walls. Built in 1962, the mall has undergone many revisions and expansions, as well as a name change to Walt Whitman Shops in Huntington Station, and it’s currently undergoing yet another renovation. Shor says the lines of poetry may not be on the outside walls when the work is done, but “he will be a presence at the mall and it’s going to be very special in the new revision.”

Shor believes Whitman would approve “because he was a self-promoter… One of his great lines is: ‘I celebrate myself, and sing myself, and you shall do likewise.’”

“If Walt Whitman were alive today, he would get a kick out of the Walt Whitman Mall,” insists Thomas Fink, a Port Jefferson resident who is a professor of English at City University of New York-LaGuardia College and whose eighth collection of poetry, Joyride, will be published in October. “He wrote catalog poetry, ‘Song of Myself’ being perhaps the major example, and the mall is one big catalog of diverse stores that themselves are catalogs of diverse elements. And he would love the boisterous, brazen advertising because Whitman was very intent on self-promotion as a poet.”

For example, Fink cites how Whitman handled a letter that Ralph Waldo Emerson, then the country’s most illustrious writer, had written him, praising his Leaves of Grass as “the most extraordinary piece of wit and wisdom that America has yet contributed.”

“When he took Emerson’s praise in a private correspondence and made it an egregious blurb, the Transcendentalist chieftain was taken aback,” Fink says.

As Kaplan points out, Whitman’s face “appeared on cigar boxes although he never smoked.”

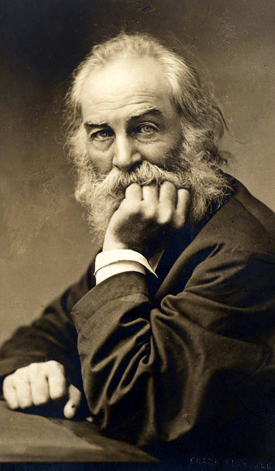

Whitman himself said, “I’ve been photographed, photographed and photographed until the cameras themselves are tired of me.” One of the most famous images was taken by the acclaimed Matthew Brady.

But it’s his free-verse poetry eschewing the constraints of set rhythm and rhyme that, Kaplan and other scholars say, established him forever as “the bold voice of joy and sexual liberation, the chronicler of the century of democracy, science, progress and steam.”

But it’s his free-verse poetry eschewing the constraints of set rhythm and rhyme that, Kaplan and other scholars say, established him forever as “the bold voice of joy and sexual liberation, the chronicler of the century of democracy, science, progress and steam.”

And his influence still inspires.

“Poets writing in English owe a great debt to Walt Whitman,” says Sandy McIntosh, author of eight poetry collections and a former literature and creative writing professor at Hofstra University and Long Island University as well as the publisher of Marsh Hawk Press, based in East Rockaway. “He wrote and encouraged others to write in plain, straightforward English, the typically American form of speech. Rather than poetry being found in complex rhyme and rhythm schemes of classical English poetry, Whitman showed that from our commonplace speech real poetry would spring.”

The Walt Whitman Birthplace State Historic Site and Interpretive Center is located at 246 Old Walt Whitman Road in Huntington Station. Learn about its many treasures and how you can help safeguard Whitman’s legacy for future generations by calling 631-427-5240 or visiting www.WaltWhitman.org.