The masked men had gone through endless weeks of planning and false starts before arriving at John F. Kennedy International Airport in the middle of the night on Dec. 11, 1978.

Despite the frigid air they were determined to execute a plan that would net them nearly $6 million—$21 million in today’s dollars—the largest theft of untraceable money in the country. Tonight they would score.

A Ford Econoline van pulled into the cargo area of Lufthansa Airlines at 3:12 a.m. Inside were six hooded men, four of whom jumped out and entered the building.

As expected, the guard was on his scheduled break. They ran up a flight of stairs, unfettered by security.

Meanwhile, the van positioned itself inside a gated area while a late model car, its headlights off, pulled into the terminal parking lot.

Tension filled the van, and despite temperatures in the 20s, the two men inside were sweating. They removed their masks to cool down. That was their first mistake.

They did not expect to be confronted by two employees, who could now identify them. One witness was beaten and pistol whipped. Bloodied and bruised, the victim would be held up as the example to show other workers what would happen if they did not cooperate.

Inside the cargo area, other Lufthansa employees were being threatened with their lives and ordered to lie on the floor. One employee was forced to open the vault and the gang took out cartons of money and jewelry.

Just over an hour later, at 4:21 a.m., the robbers ordered their captives not to move for 10 minutes.

Outside, the van pulled up and the loot was loaded in. Four men got into the Buick and both vehicles drove off. No one tried to stop them.

What happened that night, 35 years ago this month, is a story that spawned books and movies.

Despite the media attention and teams of law enforcement agents investigating the case, a dark mystery still surrounds that night. So do the unsolved murders left in its wake.

All those involved with the robbery who knew where the stolen money went are believed to have taken that knowledge to the grave, because they’ve either been found brutally murdered or been reported missing.

Parnell “Stacks” Edwards, who was supposed to get rid of the van but instead went to his girlfriend’s house, was the first to turn up dead. Edward Eaton, who was depicted in the movie Goodfellas as dying in a refrigerator truck, was actually discovered in Brooklyn.

His body had been lying in the truck for several days. Because it was so cold, it took days to defrost.

Frank Vincent, aka Billy Batts, was murdered twice. He was shot in a bar and put in the trunk of a car. When his killers got upstate, they saw he was still alive, so they killed him again.

Tommy DeSimone was cut in half with a chainsaw and dumped into the Atlantic Ocean. After buying an expensive car with proceeds from the heist, Louis Cafora and his wife, Joanna, were never seen again. Teresa Ferrara, the alleged mistress of Tommy Desimone, was last seen hurrying from her beauty shop in Bellmore. Later she was found murdered, her body dismembered.

In total, at least 16 members of the original crew who both planned and executed the theft were reported missing or turned up dead.

Louis Werner, who died in 2007, was the only one ever convicted for the Lufthansa heist.

James Burke, the late gangster who planned the heist, was the only one convicted of a related homicide.

Despite the story being told again and again, few people knew the key role a Nassau County police sergeant played in helping to identify the perpetrators—until now. Through thorough police work and natural instincts, he turned a wannabe gangster into a witness whose testimony helped convict Werner.

RAGS TO RICHES

Bill Buckley’s story begins a week after the heist, when investigators were desperately trying to find evidence against the people who committed the crime.

On the job for more than 10 years, Buckley, at the time a Nassau County Police Department sergeant, was by all accounts a good cop. Among his other duties, he was assigned to check on ‘licensed premises’ for violations of the Alcoholic Beverage Control Law. He focused on the ones that openly catered to the mob.

The mafia had found a loophole in the law that enabled them to incorporate as a not-for-profit fraternal organization, which then enabled them to serve alcohol without a license.

Many members brought their own bottles at the clubs that were known for drugs and prostitution.

“Most people going into a place like this signed their name in the membership book using a creative alias like Mickey Mouse or Donald Duck,” says Buckley, now 66, retired and living in Texas,.

While investigating one of these clubs, Buckley noticed the name of Billy Fischetti, a man Buckley knew was part owner of the Bellmore Taxi Company at the time. Buckley describes Fischetti as “a half-assed wanna-be gangster” who was always getting involved in illegal scams.

But, it appeared, he wasn’t all that smart a wise guy. Fischetti had used his real name.

Buckley knew Fischetti from Buckley’s days working for Bellmore Taxi before he became a Nassau cop and once he was on the force he used Fischetti as an informant.

Fischetti was a known gambler with an eye for women. At about 6-feet, 5-inches tall, he towered over most of his associates and he was also overweight. Buckley described him as “a baby Huey type.” His affinity toward women would later pit him against the members of a very dangerous crime family.

Fischetti’s majority interest in the taxi company was proving profitable. He owned two houses at the time, one a two-family in Merrick, and another a newly built large home in Bellmore.

Covering all the angles, Fischetti was also a member of the Bellmore Republican Club.

Buckley tried to get information on a club he wanted to bust from Fischetti. What the investigator didn’t know then was that Fischetti was in trouble and he was looking for Buckley—to ask for help.

In plain clothes and driving an unmarked police car, Buckley approached Fischetti at the cab company. They left the office together and walked to his car. Fischetti told Buckley he would help him but in exchange he needed cash and protection from the mob.

Buckley said that once Fischetti had given him the information he sought, Fischetti wanted him to go to the FBI and let agents know that Fischetti would become a witness for the feds if they paid Fischetti $40,000. Fischetti also said that if the FBI refused payment and still tried to talk with him, he would tell them Buckley had made it all up.

Buckley was intrigued. So he let Fischetti talk.

Fischetti then told Buckley that he was involved in the Lufthansa heist, and in fact had stolen money from Lufthansa—before the big heist in December. Months before, he had entered the warehouse, put on a company rain slicker and walked to the money room. He had picked up a canvas bag with $23,000 in it and walked out.

Amazed at how easy it was, Fischetti said his experience became the blueprint for the infamous Lufthansa heist by the organized crime guys.

“You really stepped in shit this time,” Buckley recalls thinking as he heard the story.

“When I asked Fischetti why he wanted to become a federal witness, he admitted it was because of him needing the $40,000 for protection. When I asked why he needed protection, he said [it was] because after the job went down and he read about how much money they had gotten, he tried to shake them down.

“Of course, the response from the bad guys was that if he opened his mouth, they would kill him,” Buckley says. “It was typical of Billy to think he could muscle, or extort, guys who had done a robbery of that magnitude. I also thought it was logical and realistic that they would kill him if he opened his mouth like he had threatened to do.”

Immediately following their meeting, Buckley wrote down all the details of his conversation and went back to see his boss.

Buckley knew the information was good. He knew Fischetti and the guys he hung out with.

The investigation was being led by the FBI and involved myriad other law enforcement agencies.

Now, because of Buckley’s snitch, Nassau County police had reluctantly become a part of it.

WALKING IN THE SAND

Some of the planning for the Lufthansa heist took place at the Sunrise Bowling Alley, now a parking lot in Bellmore, where there used to be a little bowling and a lot of gambling.

The bar inside was a gathering place for the guys to drink, play cards, make and settle bets. Time had stopped there in the ’50s as red plastic topped turntable bar stools surrounded the horseshoe-shaped bar. Small tables blended into the dim, smoke-filled light.

The bar was often crowded, the noise level high and the stakes even higher. The bartender doubled as a bookie. Buckley had locked him up once while working undercover.

Card games waited until the bowling alley was closed and locked up. This was a meeting place for some of the most dangerous men in the country, men who viewed murder and death as a way of life.

Ironically, about a block away was Bellmore Bowl, a meeting place for off-duty cops which is now The Pool House Billiards & Sports Café.

Back then organized crime was rampant on the Island.

Joe Coffey, an expert on La Cosa Nostra, was commander of the Organized Crime Task for the New York City Police Department.

After the Lufthansa heist, the NYPD commissioner asked Coffey, who had experience with both the mafia and homicides, to help investigate. Coffey knew immediately that it was James Burke, an associate of the Lucchese family, because the crime was too sophisticated for John Gotti, part of the Gambino family, to pull off, Coffey says.

Those were the two crime families who controlled Kennedy Airport. They both regularly robbed cargo trucks in the area and routinely bribed law enforcement to look the other way.

“They had their tentacles everywhere,” Coffey says. “Their corruption went right to the White House.”

But knowing and convicting are two very different things. At that time, “going after criminals was like pissing in the ocean,” Coffey says. Even in jail they got special privileges.

BEYOND THE SEA

When Buckley went to see his Nassau police commanding officer about how to handle Fischetti, he landed in a political quagmire.

After the briefing, Buckley was asked to leave. A lieutenant was called in to discuss what to do next.

Cops are usually not good with waiting. They are trained to take charge and react. Buckley was no different.

About to get his first lesson in departmental politics, Buckley was “going crazy with frustration,” he says. Buckley knew his boss did not get along with his superior.

Eventually, Buckley was ordered to report to the local FBI field office, but he was surprised the police department’s Robbery Squad did not take over.

“My thoughts were that I would give our guys the information and they could feed it to New York City Robbery Squad so that they would be owed a favor back from [them] in the future,” Buckley says. “That would have been the logical thing to do, but many of the upper staff on Nassau County Police Department enjoyed attending the FBI National Academy for three months at Quantico, Virginia, and I think that because the local office of the FBI could say, ‘Yea’ or ‘Nay’ on who attended, the big bosses wanted to keep the FBI happy.”

Buckley was nervous. He felt out of his element. He already had had one negative experience with the FBI. But while Buckley was following orders to meet with the federal agents, members of Coffey’s group were already following up on their leads.

Neither were fans of the FBI, which is not unusual for local law enforcement. Coffey’s group had their own name for the FBI: “Famous But Incompetent.”

“Nobody likes working with the FBI,” Coffey says.

Buckley went to the FBI office and gave his information to the local agents. As he read from his notes, he saw a notable change in their demeanor. By their reaction he knew that he was giving them information that had never been made public.

He knew about Werner, who played a major role in the robbery. Werner was the employee at Lufthansa who had set up everything so Fischetti could walk in and walk out with a bag of foreign currency as a dry run. Werner was also part of the group that gambled at Sunrise bowl in Bellmore.

Both Nassau police and the feds asked Buckley why he believed Fischetti, considering his past.

“That was just dumb reasoning,” Buckley says, “because who would know about crime and street life if he wasn’t part of it?”

Buckley was subsequently ordered to work with the FBI. Unfortunately, he says, he was not paired with one of their best agents—instead, his new partner was a rookie.

“He had no background in working the streets and was not a native New Yorker,” Buckley says.

Buckley wasn’t happy, but he had to follow orders. The pair’s first move was to call the Bellmore cab company where Buckley was told that Fischetti had taken the day off.

Buckley didn’t want to call his home, believing Fischetti’s wife was not involved in the heist herself and probably knew nothing about her husband’s involvement, either.

“I foresaw a lot of heartache coming to this lady as it was and I didn’t want to add to it,” Buckley recalls.

They drove passed Fischetti’s house and all the places where Buckley knew Fischetti hung out. There was no sign of him.

“The next day I remembered that Billy [also] owned a two-family house in North Merrick, and I thought there was a possibility he might be crashing there,” Buckley says. “Sure enough, when we drove past the house, I saw his taxi parked in the back of the driveway.

The agent wanted to leave and find a phone to call in and get direction as to how to proceed next. I was strongly against doing that. Unfortunately, the agent was driving, so after looking high and low for this guy for two days, we left the scene so he could call his boss.

“I was furious,” Buckley says. “His boss told him what I had said to do: ‘Sit on the house until Fischetti left, then stop him and pick him up.’ Even if he didn’t want to come with us, there was enough cause to bring him in anyway.”

Eventually, Fischetti appeared. On their way to the local FBI office, Buckley asked Fischetti why he was avoiding him. Fischetti told him that he had received a threatening phone call warning him about talking to the cops.

“He said that he was being watched and he had been seen sitting in my unmarked car talking to me,” Buckley says. “He told the bad guys that he didn’t tell me anything and that they should check with people from Bellmore who knew me as a cop when I often came around. The bad guys told him that if he talked to me or any other cops he would be dead. So that was why he was avoiding me.”

Fischetti was surprised when Buckley found him, the sergeant recalled.

“All this was occurring before the bodies started to pile up from fallout from the robbery,” Buckley says. “We drove back to the office, where they escorted Billy into the back and told me, ‘Thank you very much but we don’t need anything else from you from here on.’”

“I had to agree that the jurisdiction of the robbery had been within New York City, and that the type of robbery made it a federal crime,” he says. “Since we had nothing that had happened in Nassau, I just had to bow out of the case.”

Few people were even aware of what he had done. Meanwhile, the number of bodies related to the heist continued to climb.

“In about approximately 65 percent of murders, the people know each other,” Coffey says. “But, the Italian mob killed for a reason; economic, vengeance or someone was disrespected. In addition, all gangland hits had to be approved by the commission,” or heads of the five mob families.

With all the murders being committed, Buckley was happy to be back at his own job.

“After the bodies began to mount up of the guys who had been involved in the robbery, I realized that the big crime bosses were eliminating anyone who could connect them to the crime,” Buckley says. “I never believed there was a code where organized crime guys didn’t hit cops, so I began to carry my gun off-duty, even around my house.

“As far as I was concerned, if they had asked Billy who the cop was he had been talking to, he would have given me up in a heartbeat,” Buckley says. “If they thought he knew too much, they would kill him and maybe think about killing me.”

MANNISH BOY

Fischetti eventually went on to testify against Werner in open court, retelling the jury the same things that he had said to Buckley during their first meeting at the cab stand in Bellmore.

“Werner called and said that I was stupid…that I had financial problems while he was set for life,” Fischetti testified, according to a report from The Associate Press at the time. “In late 1977, Lou had an idea on how to make a big hit…he said he’d grab a big package, and my job would be—a truck driver—to get it out of the airport.”

Werner’s lawyer, Stephen Laifer, was quoted at the time saying that Fischetti’s testimony would cast “a doubt big enough to drive a Brink’s [armored] truck through.” The jury didn’t buy it.

Werner was convicted for the robbery in May 1979. Buckley recalls that despite his fears Fischetti later returned to Bellmore and lived there until he died more than a decade ago.

“I can’t understand why he wasn’t murdered like so many of the other people with knowledge of this crime,” Buckley says with amazement.

The money was never found. Coffey says his guess is that “Burke’s daughter got it.”

That mystery may never be solved. The string of violent killings will probably go unpunished. Coffey says that even though Werner was the only person ever convicted for the robbery—Burke was convicted of a related murder—he has no regrets.

“I’m a believer in the criminal justice system, but the justice that they got was far greater than what we could have done to them so I was pretty happy,” Coffey says. “Burke died in prison and the other vermin died in the street. Who cares?”

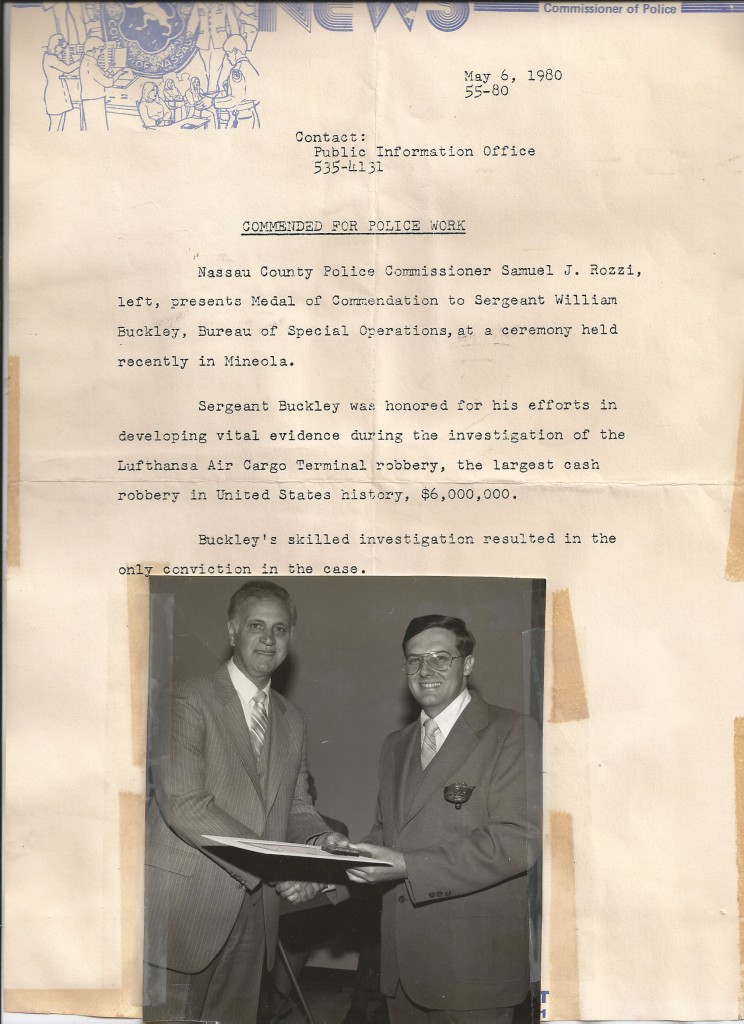

In 1980 Buckley received the Medal of Commendation, the second-highest award in the Nassau County Police Department, for his work on the case. During his career he also won the respect of those he worked with.

“Good cops are always a step or two ahead of their peers,” said retired inspector John Sharp, “Bill Buckley was way out ahead of even the best cops. He was tenacious and a leader in every sense of the word.”

Buckley had been ordered by the FBI not to tell anyone in the NCPD that he was working on the Lufthansa heist. He retired after 24 years on the job.

Now, 35 years later, Buckley’s story is finally being told.