• Crime Lab Misdeeds Have Cost Taxpayers More Than $2.4M

• County Still At Least Year And Half From Opening New Lab And Ending Fiscal Bleeding

• D.A. Caught By Surprise, Seeks Review after Being Informed by the Press

• Outraged Lawmakers Demand Hearings Upon Learning Latest Revelations

An analyst falls through the floor while testing evidence to be used in a criminal case, his legs literally dangling through the ceiling of the work stations below. An inspector notes that a steel escape ladder, ordered to be installed three years earlier as an emergency exit since the laboratory only has one entrance, sits unopened in a box on the floor, for just as long—the noncompliance simply copied and added to his new report. Analysts testing MDMA, aka ecstasy, fuddle through tests determining the criminal sentences of defendants.

These were but a few of the daily, costly antics that took place at the Nassau County Police Department (NCPD) Crime Lab—where drugs were tested, fingerprints analyzed and blood and ballistics work conducted, with the results used by prosecutors of the Nassau District Attorney’s Office in criminal cases. Shuttered since February 2011, much of this all-important testing, along with the re-testing of thousands of cases, were outsourced, with Nassau County Executive Ed Mangano and District Attorney Kathleen Rice pledging to already cash-strapped taxpayers that they wouldn’t be charged “one single penny” for the misdeeds—of which two police commissioners, two county executives and prosecutors claim they were absolutely clueless about its persistent problems until inspectors stripped the lab of its accreditation three years ago.

The Long Island Press has now learned that despite assurances from county officials to the contrary, Nassau taxpayers have unknowingly been paying millions of dollars as a consequence of the years of lax oversight, mismanagement, neglect and/or willful ignorance at the county-run police crime laboratory and will continue to shell out hundreds of thousands of dollars more because of these improprieties far into the foreseeable future.

These are just some of the newest revelations in this infamously eye-opening, disgraceful and continuing saga.

Upon being informed by the Press of the hefty switcheroo onto taxpayers’ backs, a taken-by-surprise District Attorney Rice is calling for a review by Mangano.

“After the Nassau County Police Department crime lab was shuttered at my insistence due to inexcusable errors, the Department committed to using funds forfeited by criminals—not taxpayer dollars—to pay for retesting costs,” says Rice in a statement. “If the Police Department has done otherwise, I encourage the County Executive to review this matter and ensure that taxpayers are not affected.”

Team Mangano refused to comment for this story, instead, the county executive’s senior policy advisor Brian Nevin referred all inquiries to First Deputy Nassau Police Commissioner Thomas Krumpter.

“The county wanted to ensure that all necessary testing was conducted,” explains Krumpter. “The testing was significantly more extensive then was originally anticipated.”

DISGRACED

The closing of the troubled, yet oh-so-critical crime lab by Mangano in February 2011 at the behest of Nassau District Attorney Rice followed a scathing November 2010 report by the American Society of Crime Laboratory Directors/Laboratory Accreditation Board (ASCLD/LAB). The Missouri-based nonprofit, responsible for ensuring public and private forensic science labs around the world comply with universally accepted accrediting standards, had discovered 26 areas of noncompliance—including 15 deemed “essential” and 10 “important”—and placed the lab on probation.

It was the second time in four years the laboratory was put on probation, the first being in 2006; the crime lab has been cited by the group for myriad improprieties each year since it began inspections there in 2003, and Nassau remains the first and only such municipality in the nation to hold such dubious distinctions.

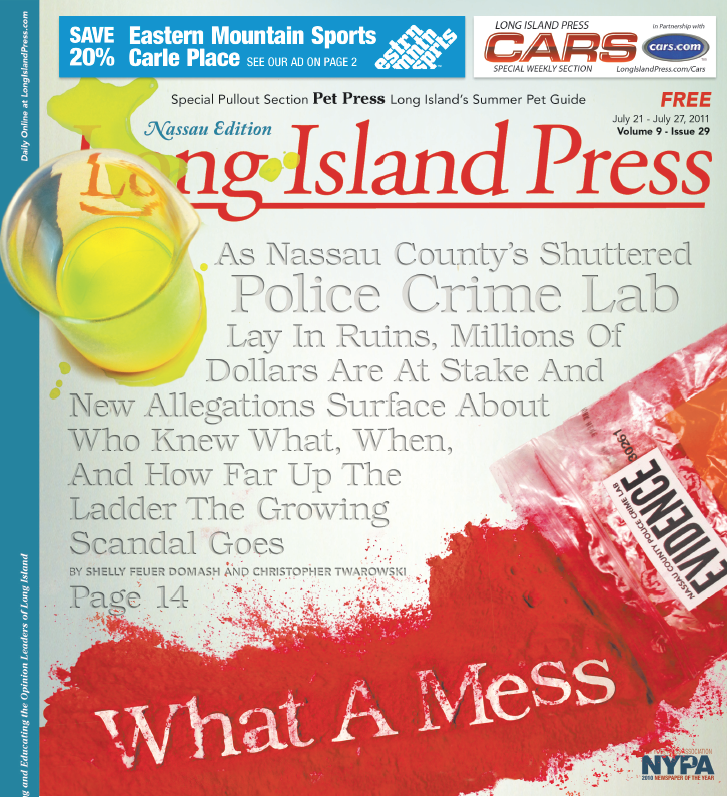

As reported by the Press in a July 2011 expose titled “What A Mess,” the ASCLD/LAB report painted a hellish portrait of the critically-important facility, among its findings: that evidence sat unmarked and lacking the proper seals designed to protect its integrity; evidence was mishandled, improperly stored and safeguarded; internal audits ensuring the lab’s compliance with accreditation standards were never conducted; control and standard samples mandated for use and documentation to ensure the validity of examination results were not utilized; equipment and instrumentation were not calibrated and documentation lacked the necessary oversight used to identify exactly who conducted the tests, among a long laundry list of other damning problems.

The consequences of the lab’s closure have been unprecedented. Rice ordered sample evidence in about 3,000 felony drug cases dating back to 2007 to be retested by Willow Grove, Penn.-based laboratory The National Medical Services (NMS). Rice’s spokesman at the time, John Byrne, told the Press that because each felony case involved multiple samples, the total number required to be retested could “go into the hundreds of thousands.”

The county Medical Examiner’s Office (MEO) took over some of the NCPD crime lab’s functions and is currently accredited in biology (body fluid identification and DNA testing) and latent print comparisons (performing analysis and comparison of fingerprints), according to assistant director and quality manager of the MEO Karen Dooling. This lab will be applying to extend its accreditation scope to include drug chemistry (controlled substance and quantitative analysis), fire debris and latent print processing “mid-year 2014 dependent upon some facility issues that need to be resolved,” she says, adding that if they “make application mid-year, I anticipate we would be accredited in those areas by fall/winter 2014.”

“The remainder of the anticipated disciplines Firearms/Toolmarks and Digital Evidence,” she continues, “will not move forward until we are in the new crime lab facility unless additional space becomes available.”

That “new crime lab facility”—something in the works in one stage or another for at least a decade, according to Krumpter—is still yet-to-be constructed and will be located in New Cassel.

Krumpter puts the timetable for construction of this new facility at about August 2015, explaining: “The Nassau County Legislature has approved bonding and the construction budget. The contract is completing the routing process. The construction is slated to commence in February and be completed 18 months from the start date. Bonds for the new facility are issued as the money is needed.”

In the wake of its closure, New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo ordered an investigation into the lab by Inspector General Eileen Biben, whose probe included the review of tens of thousands of emails and documents and more than 100 interviews. Ultimately, its 184-page November 2011 report discovered “systemic problems” yet failed to hold a single person accountable.

Former County Executive Tom Suozzi, Rice, Mangano and former Nassau County Police Commissioner Lawrence Mulvey all told investigators they were absolutely clueless about the facility’s myriad problems—despite many of its ailments’ stark visibility and, in the case of Mulvey, a deputy chief of detectives telling investigators he’d hand-delivered the commissioner a report about the lab’s many issues.

In fact, much of the mess was pretty much impossible to miss.

“’There has been a problem with water seeping through the floor in the Firearms Sections Lab which is in the basement of police headquarters,’” reads Biben’s report, citing a previous inspection’s findings. “’This has caused the relocation of two comparison microscopes to laboratory space on the second floor. Examiners must frequently go back and forth between the firearms lab in the basement and the location of the scopes in order to complete their analytical assignments.’

“Sgt. Robert Nemeth, the longtime Firearms Section Supervisor, testified that the water problem had persisted unattended for years,” it continues. “At one point, the floor had rotted to the extent that one analyst fell through the floor. When Nemeth brought the dire situation to the attention of the chiefs, he was told ‘to do more with less.’”

Biben also ordered an expanded review of the lab’s results, since “an extensive retesting plan of the lab’s drug chemistry results revealed preliminary results that found inconsistencies in at least 10 percent of the cases.” The police department tells the Press that every felony case and every misdemeanor case from 2007 through 2010 were submitted for retesting.

A Mangano spokeswoman had put the tab for the retests as high as $500,000, to be paid for by asset forfeiture funds—monies obtained through the confiscation of proceeds or substituted proceeds of a crime, designed to take the profit out of illegal activities and strip criminals of their ability to continue such activities. These funds supplement, not supplant, a police department’s budget. Asset forfeiture funds cannot be used for things that are already budgeted. Such monies could, say, fund additional hazmat suits, bulletproof vests, the county’s much-touted Gun Buyback Program or even marine patrol boats.

In March 2011 Mangano and Rice touted this in a joint announcement, promising cash-strapped taxpayers who’d been financing the supposed maintenance and operations of the all-important lab that residents wouldn’t be spending a cent for its remediation.

“Nassau County District Attorney Kathleen Rice and County Executive Edward P. Mangano announced today that the retesting of samples for approximately 3,000 felony drug cases will be paid for entirely with Nassau County Police Department asset forfeiture funds, not with taxpayer money,” pledges their statement [Read full statement below]. “It is imperative that we restore confidence in our evidence testing procedures and we will do that without asking the taxpayers of Nassau to pay for even one single penny.”

Not everyone was impressed—after all, those funds were intended to supplement the police force, and would have gone to other much-needed supplies and initiatives instead of having to be re-routed to clean up a mess which never should have taken place in the first place.

As David Shapiro, an assistant professor of economics at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, explained, just because the crime lab’s screw-ups were being footed by forfeiture funds doesn’t mean Nassau taxpayers weren’t still ultimately paying for it.

“It is not simply found money that they can say doesn’t come out of taxpayer funds,” he said. “It should be used to defray other unexpected expenditures, instead of being used to pay for something they should have done right the first time.”

“That’s robbing Peter to pay Paul,” blasted Joseph Lo Piccolo, past president of the Nassau County Criminal Courts Bar Association. “It doesn’t come from a tree. It doesn’t come out of the air. It comes from the taxpayers.”

The Press has learned that not only has the police force and Nassau taxpayers lost out on the benefits of nearly $1 million of asset forfeiture funds, but the county has also been paying for the re-testing and review of evidence with more than $1.1 million in police operating funds—in other words, a far cry from the originally anticipated $500,000 and exactly what county officials pledged they wouldn’t be using to pay for the preventable disaster, “taxpayer money.”

Additionally, taxpayers have also been footing the bill for “first-time forensic analysis of crime-related evidence,” as the NCPD explains it, to the tune of more than $1.3 million—$1,330,788.60, to be precise.

In all, the re-testing, review and new testing has cost Nassau taxpayers more than $3.2 million: $766,557 of asset forfeiture monies and $1,127,385.30 of operating funds have been spent, to date, “in support of this re-test and review program,” says the police department; and $1,330,788.60 in operating funds has been spent for “first time forensic analysis of crime related evidence,” states updated figures from the department, also compliments of county taxpayers.

And that’s not sitting well with some county lawmakers, who were also left in the dark about the public monies being used until informed by the Press.

“This directly contradicts what was presented to the legislature,” blasts a fired-up Legis. Dave Denenberg (D-Merrick), demanding a legislative hearing be held into the matter. “It’s like police overtime: It’s always well over budget and it always is in direct contradiction to promises made by the county executive’s office…in committee hearings.”

He bemoans the fact that the cost overruns will likely mean other county services will suffer, that the new lab was originally supposed to open this year, and doesn’t expect the legislature’s Republican majority to act on his calls for such a hearing into the issue, same as last time he called for a crime lab hearing, he laments.

“This is costing Nassau County taxpayers because the administration can’t run a crime lab and can’t stay within budget as to what it outsources,” he continues. “I could add this to a list of 10 issues that cry out for hearings that the Republican majority refuses to hold.”

“It’s definitely a revelation!” slams an equally surprised and outraged Democratic Minority Leader Legis. Kevan Abrahams (D-Freeport), who is also demanding hearings. “I wasn’t aware of this at all. I was aware of the $760,000, but the $2.4 million on top of that, I was not aware of that at all.”

“I know we finally got our act together to put together a [$40M] bond package to pay for a new lab, but this is taxpayer money that’s going to go out the window from this point until the new lab is built,” he continues.

Nassau Legislature Presiding Officer Norma Gonsalves (R-East Meadow) declined to comment for this story.

Krumpter tells the Press the police department cleared the use of the additional asset forfeiture monies to be spent on retesting with “officials in Washington” and that under asset guidelines, the department could not go back and obtain more funds, since at this point the money would be “supplanting nor supplementing” the police budget.

That left the county taxpayers having to pay the bill.

“It ran a lot higher because when it first started the scope was set at a certain level, and then as we got further into it we expanded the scope and then expanded the scope again of the retesting,” he explains. “So when we said it was going to be a half million dollars, that was based on a certain number of cases being retested. And then what we did was we went from a certain percentage of the cases to all felony cases, and then we went even a step further and we actually did a test of the percentage of the misdemeanor cases.”

“The asset funding request was based on an estimated number of tests (since then, the testing has tripled),” reiterates Krumpter in an emailed statement. “The testing was more extensive then originally anticipated. The spending was originally permitted because it was unanticipated and was not budgeted. Once the amount was approved, the department could not seek additional funding for the expansion of the testing. The use of additional funds would have created a supplanting issue. Asset funds must be used to supplement and cannot be used to supplant.”

Yet even after spending more than $3 million in tests and retests, a permanent, fully accredited crime lab facility is still months, or more likely, years away.

FAR WAY OFF

With the lab’s many issues so well-known throughout the police department for so long, as Biben’s report so clearly documents, formal architectural plans for a new facility date back a decade. Yet according to NCPD Assistant Commissioner Robert Hart, the job was only just put out to bid earlier this year.

The county Medical Examiner’s Office will be responsible for running the new lab once it’s operational—though some critics take issue with this, too.

In September 2013, Rice’s office discovered that two blood alcohol samples in two DWI cases had been “switched.” They notified the lab and the lab confirmed its mistake. According to office spokesman Shams Tarek, “The lab caught the mistake right away after we reported it to them and none of those samples were used in any trial so there was no problem in that regard.”

He added that letters went out to a total of 31 attorneys notifying them of the problem and offering to retest the blood samples from their clients. Regulating agencies were also notified.

For Brian Griffin, a defense attorney and former chairman of the Nassau County Criminal Bar Association, that’s just not good enough.

“That is exactly the kind of stuff that was happening before,” he slams. “Here we have been spending this money and we have been assured that any new testing is going to be state-of-the-art, and is going to be the best that there is to offer and we are repeating the same mistakes again.”

“One wrong test is one too many,” continues Griffin, adding that the authorities explained the switcheroo as an isolated incident and insignificant. “This is not a high school science lab we are talking about. It is a crime lab, which cannot make these types of mistakes when the outcome is so very serious.”

Tarek says they are still waiting for the results of the retesting of some of the blood samples processed by the technician who made the error.

With no central lab in operation, samples are still being sent to private vendors and the MEO, leaving many to question what has caused the delay to fix a problem that the police department has known about for years.

Those decade-old plans for a new lab didn’t originally just call for its relocation, but for the relocation of all of police headquarters, explains Krumpter, who insists he’d seen such schematics with his own eyes seven years ago.

Between 2003 and 2004, the Suozzi administration sponsored a second plan that included only the crime lab and the communications bureau being moved, according to Krumpter. At that time, a new lab would have cost approximately $20 million.

So despite years of planning, Assistant Commissioner Hart agrees it will still be awhile before the county can rely on its own lab.

“So as far as new evidence that comes in, it’s going to be an extended process and the reason for that is everything that we are doing in the world of forensic examinations has to be done by an accredited laboratory,” he explains. “The examiner’s office, while they are accredited in the world of toxicology, DNA and latent, still has to go through an accreditation process for drug chemistry, trace evidence and things like that. That is something they have to do both with the state of New York, with the forensic commission and with ASCLD American Society of Crime Lab Directors.”

This accreditation, warns Hart, is not an overnight occurrence, but, in fact, timely and complicated.

“It is not something that you call and ask and say, ‘Come out and accredit us,’” he explains. “First, you have to establish your protocols, your standard operating procedures. You have to go through a lot of casework onsite inspections, and, as you’re going through all this, ASCLD is asking questions, examining what you submitted—your protocols, your mock casework results—and when they come and do an onsite inspection, they’ll go through everything and they will issue a written report. The best-case scenario is they find everything up to their standards. Sometimes they say, ‘You need to tweak this, you need to enhance this,’ and when that happens, you have to respond to them.”

And from there the tedious requisites continue, according to Hart. The next step is to correct what ASCLD found wrong. The lab has to then send a letter to ASCLD, carefully detailing the steps they took to correct any problems. Then, more waiting.

“ASCLD can take that written response and say, ‘That’s great, terrific, we don’t need to come back and do another onsite inspection,’” explains Hart. “Or they might say, ‘That’s great, we’d like to schedule another onsite inspection,’ and they will want to come back out and look at you again. It’s a very long, drawn-out, lengthy process, very thorough.”

This procedure has to be done separately for each accreditation.

Hart puts the target date for drug chemistry accreditation, optimistically, at sometime in early 2014. He declined to speculate on when the ballistics accreditation would be complete.

ASCLD’s executive director Ralph Keaton is not as optimistic. He estimates the average time for accreditation, once the paperwork is received, at nine months to a year.

Assistant Commissioner Hart insists the accreditation process will not be negatively impacted by the move to the new facility in New Cassel.

“That accreditation process takes into account many factors, including the site presently occupied by the lab in question,” he asserts. “The fact that the lab may relocate at a future date to another site need not to adversely impact or delay that lab’s pursuit of forensic discipline accreditations based upon its current physical locale.”

Not so quick, nor so easy, says Keaton—stressing that accreditation is “not automatic.”

“We have standards that relate to the security and control of access of the facility and flow of evidence and things that are impacted by the facility per se,” he says. “So, it is not uncommon that we accredit a laboratory and that laboratory then moves to another facility and maintains their accreditation. However, there are certain things that we have to verity that are in place before that accreditation is continued for that laboratory, and of course, security and controlling access to the facility are important elements, but also associated with that is the movement of critical equipment and ensuring that the equipment that is moved from one location to another is properly calibrated and verified before it is put back online. So it is not an automatic thing.”

Keaton says his agency does not want to shut down a laboratory because it lacks accreditation, but “that doesn’t mean that the laboratory won’t be down for a period of time while they are in the process of moving and setting up the equipment and ensuring that it is working properly, and that any new equipment that is purchased is properly calibrated and that they verify that it is working properly.”

“It is very surprising to hear that Nassau County appears no closer to opening up a new crime lab,” says Griffin. “When the old crime lab was shuttered, assurances were made to the public and those in the criminal justice system that the county would be opening a ‘state of the art’ crime lab in the near future. The fact we’re millions of dollars into this and no closer to getting a competent crime lab is a terrible injustice.”

—With Additional reporting by Timothy Bolger and Spencer Rumsey

Rice and Mangano statement titled: “Taxpayers Will Not Foot the Bill For Retesting of Felony Drug Cases”