Two previous articles highlighted Fitzmaurice Flying Field in Massapequa Park, including three streets close to the Field named for the three aviato rs who flew east to west over the Atlantic in 1928: James Fitzmaurice, Hermann Kohl and Gunther Von Huenfeld. Lindbergh Street is north of them, named for the famous aviator who flew from New York to Paris in 1927. There is a fifth street, bordering Fitzmaurice’s site on the south, named for an aviator who is perhaps the most interesting. This is Smith Street and the aviator is native Long Islander Elinor Smith.

rs who flew east to west over the Atlantic in 1928: James Fitzmaurice, Hermann Kohl and Gunther Von Huenfeld. Lindbergh Street is north of them, named for the famous aviator who flew from New York to Paris in 1927. There is a fifth street, bordering Fitzmaurice’s site on the south, named for an aviator who is perhaps the most interesting. This is Smith Street and the aviator is native Long Islander Elinor Smith.

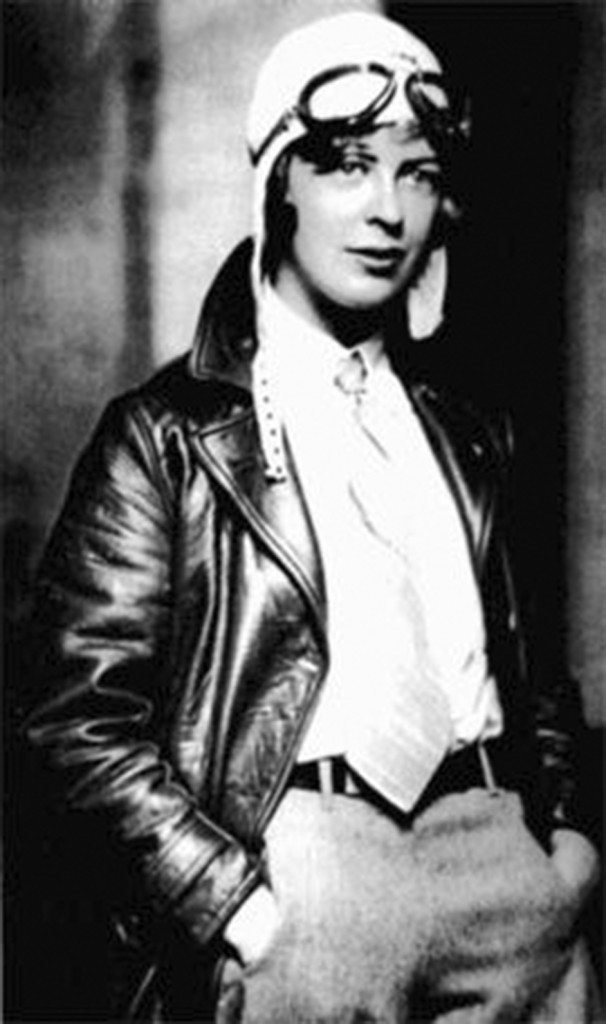

Elinor Smith was one of several women who became aviators in the early years of aviation, namely 1910 to 1930. Born in Freeport in 1911, she trained at the Moisant Flying School at Roosevelt Field and earned her license at the age of 15 in 1926. Precocious and unafraid, she set a goal to fly 250 hours solo by the time she was 16 and achieved it. She went on to establish speed, altitude and endurance records in the small planes that were available at the time, and earned her greatest fame, or notoriety, by flying under New York City’s four East River bridges. She did this on a dare in 1928, flying north to south under the Queensboro, Williamsburg, Manhattan and Brooklyn Bridges, a feat most veteran pilots did not want to try because of difficult wind currents, low ceilings and unexpected obstacles (chords with wooden weights hanging from the Queensboro Bridge, a Navy Destroyer sailing upriver under the Brooklyn Bridge).

Not to be minimized was that the practice was declared illegal by the City of New York and the U.S. Commerce Department. Smith did it anyway, in part to show the male pilots who congregated around Roosevelt Field that she was a capable pilot. For her troubles, she was summoned to meet Mayor Jimmy Walker. Instead of punishing her, he congratulated her (privately) on her stunt, while having a friendly conversation with her father Tom, who was a well-known Broadway actor. Walker later intervened with the Department of Commerce and convinced its representatives to give her an unofficial reprimand.

Elinor Smith subsequently made money from her flying skills, providing flights over the Jamaica Airport, a sandbar in Jamaica Bay, charging $5 for a local ride and $10 or $15 to fly over New York City and the Statue of Liberty. After she became the first woman to be awarded a commercial license by the Department of Commerce, as well as an International Pilots license (signed by Orville Wright), she was hired by Fairchild Aviation and by Bellanca Aviation as a test pilot. She endorsed products such as goggles and motor oil and was hired by NBC Radio as a weekly commentator on aviation issues. For her accomplishments, Elinor Smith was voted Best Wo man Pilot of 1930 by her peers, both male and female. She was especially pleased with the honor because her hero, World War I ace Jimmy Doolittle, was voted best male flyer.

man Pilot of 1930 by her peers, both male and female. She was especially pleased with the honor because her hero, World War I ace Jimmy Doolittle, was voted best male flyer.

In the early 1930s she kept busy as a stunt pilot in movies and appeared at air shows and fundraisers, especially as the depression affected more Americans. In 1933 she married New York State legislator Patrick Sullivan and decided to put her flying career on hold. She wrote in her book, Aviatrix, that it was more important for her children to have their mother on the ground than flying all over the place. After her husband died in 1956, she resumed her interest in aviation, flying jet trainers and cargo planes as a test pilot for the Air Force Association. Remarkably, she flew a shuttle simulator successfully in March 2000, at the age of 89, and the following year flew an experimental Raytheon Beech Bonanza at Langley Air Force base in Virginia. She continued to consult with aviation companies and to encourage young woman to become pilots up to the end of her long and fruitful life. She died March 2010 at the age of 98.

There are two direct connections between Elinor Smith and the Massapequas. In 1976, she appeared as one of the honored guests at Massapequa Park’s parade in honor of the United States 200th anniversary. And, in the early 2000s, she corresponded with this writer about Fitzmaurice Flying Field, indicating that the Brady Cryan and Colleran real estate firm had asked her father Tom and her to select a field around which to build homes. The Smiths selected Fitzmaurice’s location because it was level, dry and equally distant between the Southern State Parkway and Sunrise Highway. Thus, it was entirely appropriate that Smith Street be named as the southern border of Fitzmaurice Field.

George Kirchmann is a trustee with the Historical Society of the Massapequas. His email address is gvkirch@optonline.net.