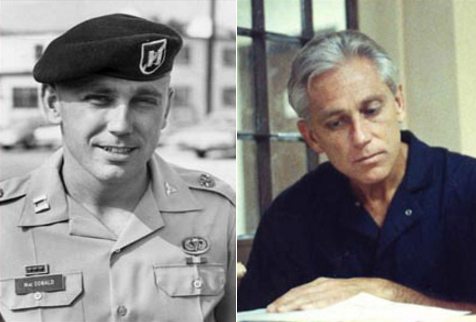

Jeffrey MacDonald, who grew up in Patchogue, was on the cover of People magazine’s Jan. 30, 2017, print edition, but MacDonald might have preferred a more affirmative headline atop his photo rather than the one which appeared. It reads, “I Didn’t Kill My Family.”

Readers from 2017 could be forgiven for wondering what this was about. Indeed, you have to be a certain age to recall MacDonald was convicted in 1979 of murdering his pregnant wife, Colette, who also had Patchogue roots, and their two daughters, 2-year-old Kristen, and 5-year-old Kimberley in February 1970. The MacDonald family was living 47 years ago this month in Fort Bragg, NC, where MacDonald was an Army surgeon and a Green Beret.

People magazine’s reporting also provided the basis for Investigation Discovery’s (ID) documentary on the MacDonald case, which premiered on the cable channel on Jan. 24. The publicity came prior to the Jan. 26 oral arguments in the case of the U.S. v. Jeffrey MacDonald in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit in Virginia.

MacDonald, a Princeton graduate who earned his medical degree at Northwestern, was convicted years after the Army had cleared MacDonald of having any involvement in his family’s deaths. MacDonald has been in prison for the crime since 1982. In the intervening 35 years, MacDonald has maintained his innocence and says his family was murdered, and he was injured, by four intruders, three men and one woman. At the trial, a mountain of credible physical evidence put MacDonald, and no one else, at the crime scene.

The 50-plus minute audio of Virginia’s Court of Appeals hearing from Jan. 26 is archived at the Fourth Circuit’s website. Having followed the case closely over the years, I did not hear anything new. MacDonald’s defense team is generally saying the same thing in 2017 as it did in 1979. There’s physical evidence at the Fort Bragg, NC, home where the murders occurred which would point to suspects other than MacDonald, the defense argued, and the crime scene was compromised by a shoddy investigation.

Moreover, the defense contends, Helena Stoeckley, who died in 1983, told numerous people she was among the four intruders who killed the MacDonald family in 1970, and they can testify to that effect.

The prosecution cast doubt on whether revisiting the crime scene would show anything which overrode the other physical evidence the jury reviewed at the trial in 1979. In addition, the prosecution pointed to the longstanding questions about Stoeckley’s credibility, something even the pro-MacDonald People magazine article acknowledged.

“At MacDonald’s trial she [Stoeckley] said she could not recall her whereabouts at the time of the murders,” the People article states, while quickly adding, “But others still steadfastly believe she was involved in the murders.” Yet nothing changes one stubborn fact. When Stoeckley was on the stand at MacDonald’s trial, and had a chance to back up MacDonald’s story, Stoeckley did not do so.

The latest turn in the MacDonald case illustrates, to my mind, the effectiveness of having defense lawyers recruit high-profile media advocates inclined to believe in a defendant’s innocence. It also helps the defendant’s cause, at least in the court of public opinion, if these investigative journalists are unwilling either to read or summarize books in their coverage which challenge MacDonald’s version of events, such as the late Joe McGinniss’ Fatal Vision.

The latest turn in the MacDonald case illustrates, to my mind, the effectiveness of having defense lawyers recruit high-profile media advocates inclined to believe in a defendant’s innocence. It also helps the defendant’s cause, at least in the court of public opinion, if these investigative journalists are unwilling either to read or summarize books in their coverage which challenge MacDonald’s version of events, such as the late Joe McGinniss’ Fatal Vision.

McGinniss’ seminal, albeit controversial, 1983 account of the MacDonald case went unmentioned in either the People magazine story or the ID production. Fatal Vision was only cited briefly in a timeline accompanying the People article.

Mike Barry can be reached at mfbarry@optonline.net. The views expressed in this column are not necessarily those of the publisher or Anton Media Group.