The vehicle that took a dozen U.S. astronauts to the moon starting a half-century ago would not meet anyone’s definition of beauty: It looked like a giant grasshopper with bugged-out eyes and spindly legs.

But the Apollo Lunar Module, also known as the Apollo Lunar Lander, was arguably the most remarkable vehicle ever built, one that brought glory not only to its manufacturer, Grumman Aerospace Corporation of Bethpage, but to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration and to the United States. The nearly 10-year project to build the LM was among Grumman’s proudest efforts, and the centerpiece of the company’s contribution to America’s space effort.

For the country, the Moon program — NASA called it Project Apollo — began on May 25, 1961, when President John F. Kennedy proposed before Congress that the U.S. “should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to Earth.”

Those LM days are now taking focus again in the minds of Grummies, as they called themselves, as the anniversary of the first Moon landing in 1969 approaches. Throughout July, celebrations are scheduled across the country to commemorate one of the most memorable days in world history. Several events are to be held at the Cradle of Aviation Museum in Garden City, which on July 20 will hold an “Apollo at 50 Countdown Celebration,” including a screening of Neil Armstrong’s first steps on the Moon.

Grummies are delighted to recall those days.

“Everybody was enthusiastic,” says Mike Lisa, now 76, of Hicksville, who was an LM environmental test engineer. “Our job was to put guys on the Moon, and that’s what we did.”

The work became all consuming at a company accustomed to work and pressure. Grumman signed a $2 billion contract — enormous at the time — with NASA in 1962.

“We didn’t know anything about a clock,” says Sam Koepel, now 90, of Floral Park, who wrote and edited LM specifications. “We did everything exactly when the company needed it done.”

Dick Dunne of West Islip, now in his late 70s, had spent most of his professional career with Grumman, beginning in the early 1960s. He worked on some technical issues with the LM before being assigned to the public relations department, in Bethpage and at Cape Canaveral.

Dunne and others were confident Grumman could do the job, but could it succeed in sending a man to the Moon by the end of the decade?

Grumman was the last of the big aerospace companies to officially sign on to the project, concentrating on engineering studies to make sure the LM could work.

“We were going through project managers like you wouldn’t believe,” Dunne recalls. “At the beginning, the project was so big you couldn’t get your hands around it.”

One of the biggest problems was weight: The LM had to be both as light as possible and yet strong to withstand the rigors of space. The issue was so crucial that NASA paid Grumman $10,000 for every pound the company managed to take off the LM, says author and space historian Andrew Chaikin. The LM wound up weighing about 37,000 pounds.

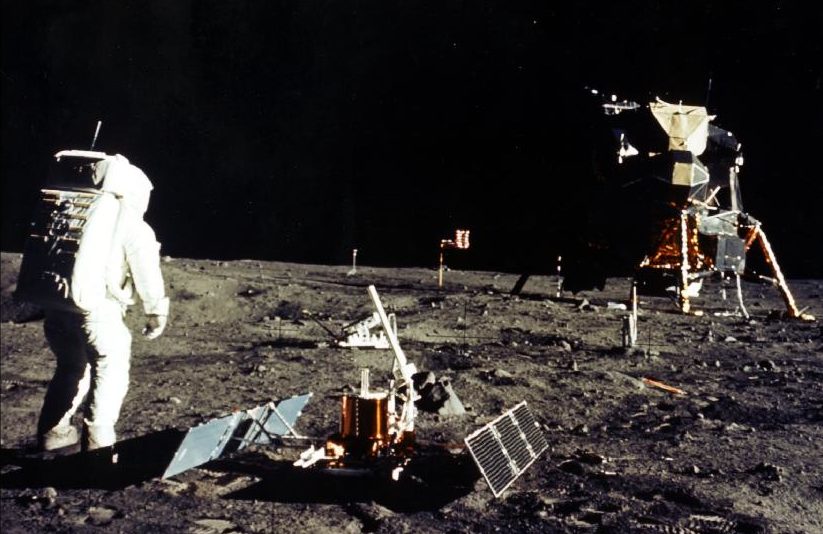

“The result was that the LM didn’t look like a spaceship. but a mechanical insect,” Chaikin says.

Six of the modules took 12 astronauts to the Moon between 1969 and 1972.

During the manufacturing years, Grumman’s workforce swelled to about 30,000 employees, the most since World War II. Then, the company employed about 40,000, building Navy Hellcat and Wildcat combat planes, on three shifts.

In the Apollo days, astronauts were a common sight in Bethpage, checking out LM systems and working with engineers. One of the most frequent visitors was Fred Haise, who was one of three astronauts aboard the ill-fated Apollo 13, in 1970. An explosion in an oxygen tank in the service module caused a dramatic loss of oxygen. Apollo 13 was forced to end its attempt to reach the Moon. The astronauts crawled into the LM, which served as a lifeboat to take them headed back to Earth safely. Haise later became an executive in Grumman’s space program.

The LM was the most challenging vehicle Grumman ever built. It was designed solely for space flight and could not be tested before it was put into service 250,000 miles from Earth. It could not operate on this planet and could never return to Earth. And, it may be the only manmade vehicle with a perfect performance record.

The most famous of the LM flights was Apollo 11, which took two astronauts, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin, to the Moon, on July 20, 1969.

In space, with two astronauts aboard, the LM was jettisoned from an orbiting command and service module, about 60 miles from the Moon. The command and service module, flown by Michael Collins, the third astronaut, remained in orbit around the Moon until the LM’s ascent stage blasted off from the lunar surface and rejoined the orbiting command and service module. The descent stage remained on the lunar surface.

The world was glued to TV sets the night of the first Moon landing. Bill Schwanker of Lynbrook, also now in his late ’70s, and an electronics design engineer, was home when Armstrong took that first step.

“Watching it sent chills up your spine,” says Schwanker.

Decades after his flight, I interviewed Armstrong. He was not an easy interview, finding the publicity distasteful. He was at heart a country boy and a man of few words.

I asked him whether he ever looked up at the Moon and said to himself, “I was there.”

He reflected on the question, smiled for the first time in the interview and, characteristically, offered a one-word response: “Frequently,” he said.