Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is an invisible potential killer. Traumatic incidents or continued stressful situations like military, law enforcement, or even many of the other first responders experience in the line of duty can create a potentially lethal cocktail of sights, sounds and images that haunt.

Clearly not everyone faced with those situations is affected, but for the ones that are, it can lead to a very dark deep place. The suicide rates are going through the roof. One in five veterans’ returning from war will develop PTSD and 36 percent of them will be classified as at risk for suicide. Veterans PTSD suicides account for more than 5,000 deaths per year. Five million Americans suffer from some form of PTSD.

Without treatment PTSD’s negative effects are sleeplessness, extreme anxiety, depression, self-loathing, and too often suicidal thoughts or actions.

The Police in New York City have been particularly impacted of late. The epidemic of police officer suicides in the city has prompted Police Commissioner James O’Neill to declare a mental health crisis in the department amid the recent spate of tragedies. The suicides have been a recurring nightmare for the nation’s largest police force and have driven a discussion about the psychological toll of police work where a discussion of mental health was long taboo.

“This was something that no one ever spoke about” said O’Neill.

Law enforcement departments all over the country are hoping to change that mindset. The attention is now focused on the epidemic. Serious people have recognized that action has to be taken.

On Long Island, both Nassau and Suffolk County Police Commissioners have, or are very soon, instituting measures aimed to stem the tide of the police suicides, including new wellness training, videos, and a full-time chaplain.

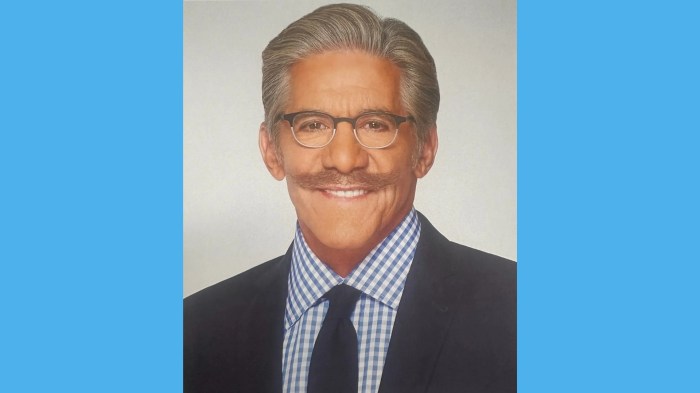

Daily, one encounters the sad news that a former military warrior or police officer has taken his or her own life. Each of those tears a small piece of my heart.

I am one of the lucky ones. I was diagnosed with PTSD from a violent shooting incident in New York City in which a uniform police officer died and I was severely wounded. However, the diagnosis didn’t come for months after the event.

The beginning of symptoms and multiple trips to the hospital set the stage for my being sent to see a professional. It was humiliating to sit in a gloomy office and be told that I was damaged in a different way from my physical injury. It was confusing to me because I saw myself as the virile, front-of-the-line, go-getter detective. Here I was being told that I had PTSD and would need psychotherapy and medication in the form of tranquilizers and antidepressants.

For more than 10 years I never left home without my pills in fear of another attack. I can tell you that this existence and resulting inability to think in a straight-line wreaked havoc on my life. I looked perfectly healthy, no scars, limp or any outward sign that I was broken inside. I used to wish that I had some outward indication because than maybe people would understand.

That was not the case. It was a lonely internal battle many times. I never quite went down the dark and deep hole, nor did I have suicidal thoughts, but I do understand that that line could be easy to cross.

Talking to subject matter experts reveals that even they approach PTSD with sympathetic but different mindsets.

Judy Elias and Michael Haltman of the Heroes to Heroes Foundation working with vets and law enforcement believe that a loss of faith is a key contributing factor in suicide deaths. They say that many suffer from moral injury that damages one’s conscience or moral compass. Their program is based upon helping to rebuild spirituality by exposing their clients to the Holy Land and the many sacred places there. They report very large success with more than 300 going through their program and returned to good mental health.

Another organization joining the fight against PTSD suicides is Code 9 who has developed The Code 9 T.U.F. Program is a Universal Peer Support Program that gives all ACTIVE duty first responders — federal, state, and local — access to safe, anonymous, and confidential peer support.

The guaranteed confidentiality is a strong lure for officers who fear departmental segregation, censure, or transfers to desk assignments.

Code 9 Heroes and Families United, a separate, but equally devoted organization, has recently posted a video that exposes some of the realities of PTSD in law enforcement officers and their families. It can be seen on YouTube. (Search: Code 9 Officer Needs Assistance).

Even horses are being brought into the battle against PTSD. Pal-O-Mine Equine Therapy is a nonprofit organization on Long Island that uses the EAGALA Model of Equine Assisted Psychotherapy (EAP). Specially trained horses are employed in the therapy session with the veterans that is more action based than talk.

This model is increasingly being used to treat veterans and their families who suffer from the effects of PTSD, such as anger, depression, anxiety, nightmares, irritability, addiction, and other debilitating conditions. In addition, EAP has also been used with veterans and their families dealing with traumatic brain injury.

The challenge is daunting for our veterans. The Department of Veterans Affairs study reveals that more than 20 veterans each day take their own lives. Annualized that is more than 7,000 deaths.

With the motto “It Takes A Community To Heal A Warrior,” Mission 22 is an organization that was created to aid the veteran population enduring difficult transitions to civilian life often exacerbated by PTSD. They have teamed up with Full Spectrum Health to create the Warrior Integration Now (WIN) program.

This is a 12-month program with the goal to eliminate or reduce the symptoms of trauma. By addressing the underlying physiological and psychological imbalances to instill a more durable feeling of calmness. The method works through balancing hormone and brain chemical imbalances, creating greater alignment with your authentic self.

Mission 22 believes that when you change your physiology you change your psychology. When you change your psychology, you change the way you see the world and your place in it. When you change that, you change the mission that drives you. and communities. To support this change, key skills of self mastery are taught for greater engagement with heart and mind.

These and many more programs, organizations, charities, and nonprofits are recognizing the depth of the PTSD problem and are responding. The methodology may be different, but the goal is the same, saving those suffering PTSD, helping prevent suicides and returning them to normal mental health and productive lifestyles.