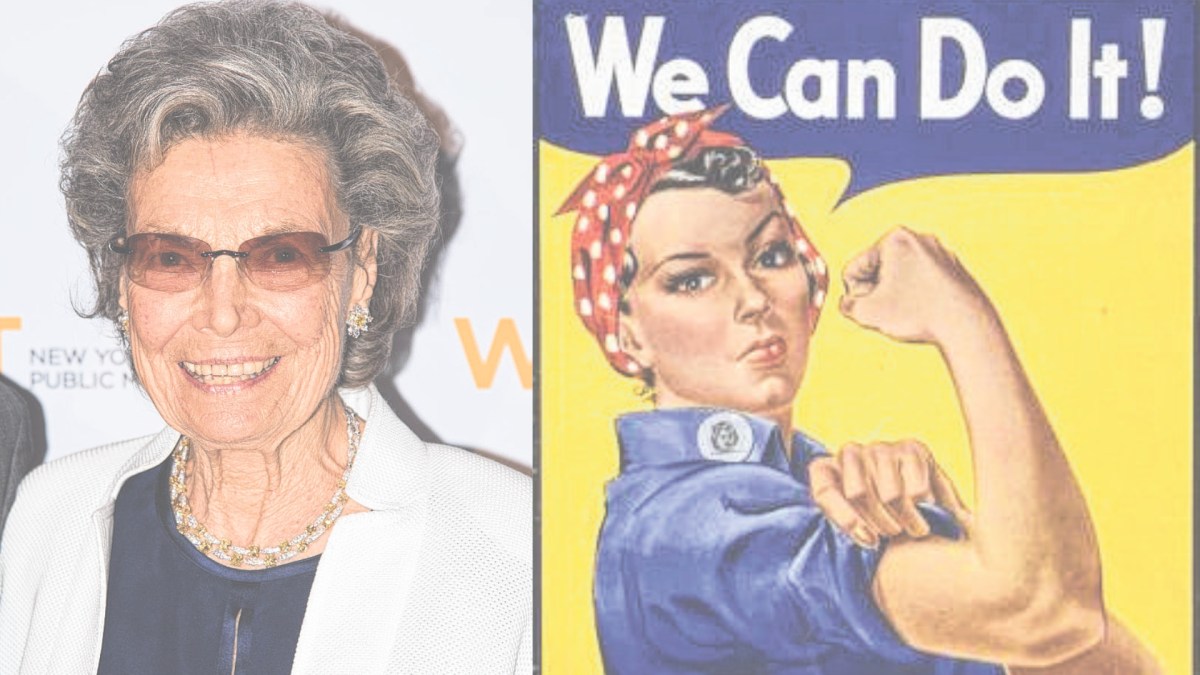

PBS fans are no doubt familiar with the name Rosalind P. Walter, one of public television’s principal benefactors. What they may not know is that in the 1950s, she and her family lived on Centre Island on Long Island’s North Shore — but before that, during World War II, she earned the nickname “Rosie the Riveter” for her record-breaking work in U.S. military factories.

TRADING RIVETS FOR ACADEMICS

She was born in 1924 in Brooklyn and raised in a wealthy New York City home; her father was chairman of E.R. Squibb and Sons, now a subsidiary of Bristol Myers Squibb, and her mother was a professor of literature at Long Island University.

“Roz” graduated from a private college preparatory school for upper-class women, and could have attended college at Smith or Vassar. Then came the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, and the United States declared war on Japan. Although she had the chance to get a formal education, she chose a different path as a way to serve her country. She was recruited as an aircraft assembly line worker, a job traditionally performed by men, at a Connecticut plant. She worked the night shift, driving rivets into the metal bodies of F-4U Corsair fighter planes — known as “Whistling Death” — that were designed in Long Island City.

She was so good at her job that It took her just several months to shatter the records formerly held by men and women. After a Hearst newspaper columnist wrote a profile on her, songwriters Redd Evans and John Jacob Loeb wrote a song about her in 1943. Rosie the Riveter became a patriotic hit, with phrases like “She’s making history, working for victory, Rosie the Riveter.”

Other morale-boosting tunes such as “You Can’t Do Business with Hitler” and “Get on the Bond Wagon” inspired women to join the workforce to support the war effort.

The same year, famous painter Norman Rockwell paid homage to women riveters working in military factories with his Saturday Evening Post cover, using a different woman as a model, as did the 1944 film about the icon. Posters and other images of the day depicted women dressed in overalls, their sleeves rolled up, wearing kerchiefs, tying back their hair, and flexing their biceps.

By 1945, 37% of the civilian workforce was made up of women.

Read also: How Long Island Women Helped End Prohibition

SOWING THE SEEDS OF THE WOMEN’S MOVEMENT

This hard-driving riveter did not limit her successes to excelling at what was typically viewed as a man’s work. As the Daviess Library County Public Library pointed out, “The message and iconic images involving her (and others) have resonated with many for years as an inspiring sign of female empowerment.”

And The Washington Post reported that during the war, “between 5 and 7 million women worked defense industry jobs, according to the Labor Department. Some hadn’t previously been employed.”

Through her work, Walter was an early shatterer of the glass ceiling, a previously invisible barrier that women broke through because many entered the workforce to replace the men deployed to fight — but at that time, women earned barely 71 cents on the dollar of what men were paid.

According to PBS Weekend, Walter later reminisced, “They had to find out whether women could get the same pay for doing the same job so they timed me after I had learned them all and I broke all the men’s records, so they had to pay the women the same amount.”

After the war ended, other women became models for Rosie posters and magazine covers. Several have claimed that they were the original Rosie, but the consensus is that Walter was the real Rosie, the one who became embedded in American culture: Daughters of Rosies were called “Rosebuds” and sons were called “Rivets.”

In her later years, Rosalind Walter gave generously to PBS and cultural institutions, including a number on Long Island: LIU, the North Shore Wildlife Sanctuary, the North Shore Wildlife Sanctuary, and Grenville Baker Boys & Girls Club.

As for why she chose to support public TV, PBS reported that Walter said that she “wanted all Americans, whether they were rich or poor, well educated or not so well educated, to have equal access to news and knowledge and the arts.”

Walter died at age 94 in 2020.