Every January, well-intentioned people make New Year’s resolutions. One popular promise is to quit drinking alcohol altogether, or drink less. There’s even a movement called Dry January that’s devoted to the concept: In 2022, one in five adults said they had participated in Dry January, reports Forbes.

But some 100 years ago, the idea of an alcohol ban was the backbone of Prohibition in America. The manufacture, sale, or transportation of alcoholic beverages was prohibited in 1919, when liquor sales were outlawed by the 18th Amendment. Complete or partial abstinence — called “temperance”— was the aim.

On Long Island, though, lawbreakers rejected Prohibition. The area was called “Rum Row,” because ships anchored offshore brought in rum from the Caribbean Islands, brandy, and French sparkling wine, defying the law. The controversial amendment was so despised that it was tossed out in December 1933.

The law’s repeal came about largely because of the efforts of Long Island women.

SPEAKING SOFTLY

The Washington Examiner described the liquor- and cash-fueled years during a great economic boom as “The Dry Decade … the decade of hot jazz and short skirts.” As the Roaring 20s swept across America, New York City and other major cities raked in profits by operating unlicensed establishments that sold liquor. Patrons wearing formal attire would knock on a storefront door or a back-alley entrance, a peephole would open, and the patrons would supply a secret phrase or word to enter. These mostly upper-class, after-hours establishments were called “speakeasies” because the passwords had to be spoken softly before admission was granted. Inside, the crowds would socialize, dance to music by bandleader Guy Lombardo and other notable entertainers, dine, and imbibe. The booze was often substandard, so bartenders added fruit juice to drinks to disguise the poor taste, creating cocktails, according to the Long Island History Journal. By 1930 the city had around 32,000 speakeasies, as estimated by New York City Police Commissioner Grover Whalen, New York Magazine reported.

BOOZE BOATS AND THE KLAN

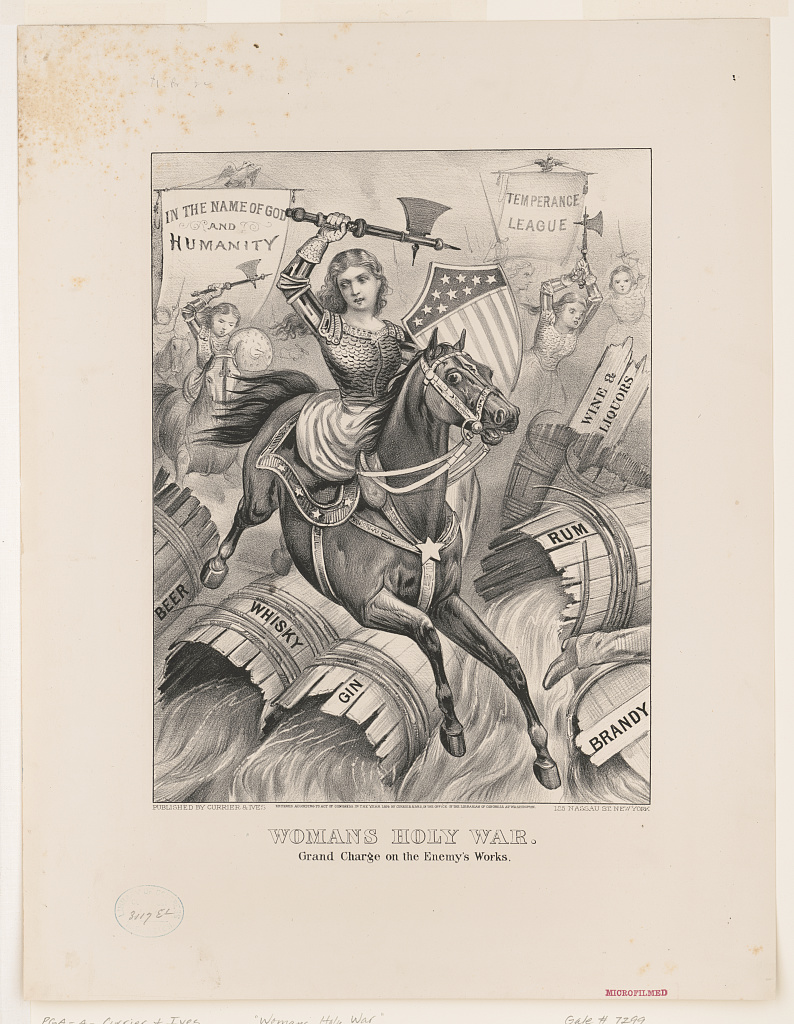

The rum-running boats supplying the speakeasies had appeared in reaction to the booze-banning amendment that was popularly called the Volstead Act. The temperance movement that led to the law had emerged during the 1800s, when advocates “aimed to reduce alcohol consumption and prevent alcoholism, drunkenness, and the disorder and violence it could result in,” according to the Jack Miller Center at the University of Virginia.

Throughout the 1920s, anchored 3 miles off Long Island’s South Shore in international waters, fishermen and baymen illegally ferried liquor to the mainland. Nearly one-third of all liquor transported to Manhattan came from Long Island; Freeport was known as “Rum-runners’ Point” and Merrick Road was dubbed “Bootleggers’ Boulevard,” according to the Encyclopedia of Rumrunners and Speakeasies: Freeport During Prohibition.

Crime, much of it caused by Prohibition, soared. With officials failing to patrol the floating liquor markets, some Long Islanders sought out vigilante enforcement — enter the Ku Klux Klan.

“Klan gatherings could number more than 20,000 people, such as a meeting in Willis Field in Hauppauge in 1923 … Members participated in raids, burned crosses to threaten enemies, tipped off authorities about speakeasies and liquor stashes, and even manned checkpoints, such as helping federal Prohibition agents search motorists’ cars for liquor in Hampton Bays in 1924,” according to the Long Island History Journal at Stony Brook University.

DISMANTLING THE LAW

By 1929, many women who had supported Prohibition had changed their thinking. Nine years earlier, they had waged their suffrage campaign that won them the right to vote. They founded the Women’s Organization for National Prohibition Reform (WONPR), reflecting the modern “new woman” of the decade, to show that not all women supported temperance. As the Museum of the City of New York wrote, they believed that “Prohibition had led to a surge in unregulated and particularly underage drinking, as well as a growing sense of distrust for the rule of law.”

The organization’s members, called “Sabines,” strategized in Roslyn Heights at Jean and Edward Small Moore’s rambling country mansion, known later as the Roslyn Country Club and then The Royalton. Chairing WONPR from Bayberry Land, her 31-room estate on 314 acres in Sebonac Neck in Southampton, was charismatic socialite Pauline Sabin. Active in local and national politics, Sabin was the first woman to become a member of the Republican National Committee, but she resigned to lobby for Prohibition’s repeal.

Sabin wrote in 1932 that they would enlist “an army of women so great that its backing will give courage to the most weak-kneed and hypocritical congressman to vote as he drinks,” as reported in Liberated Spirits: Two Women Who Battled Over Prohibition, by Hugh Ambrose and John Schuttler.

Sabin pressured the Democratic Party to pledge repeal after she endorsed Franklin D. Roosevelt for president, and 11 days later she appeared on the cover of Time magazine. By April 1933, there were 1.3 WONPR members whose influence brought back booze: On Dec. 5, 1933, the 21st Amendment was ratified, repealing the 18th Amendment.