Joseph D’Alonzo, a lifelong Port Washington resident and business leader with deep family roots on the peninsula, was elected as a commissioner of the Port Washington Water Pollution Control District, saying he ran to restore focus, collaboration and long-term planning to an agency he believes plays a critical role in protecting the community’s environment.

D’Alonzo, 58, won the nonpartisan race by a roughly three-to-one margin.

He said voters rejected what he described as divisive campaigning and misinformation in favor of a steady, solutions-oriented approach to local government.

“I think public service works best when it’s collaborative and respectful,” D’Alonzo said. “You don’t have to agree on everything, but you do have to work together.”

D’Alonzo’s ties to Port Washington span generations.

His grandfather emigrated from Italy in 1912 and settled on the peninsula, where the family eventually established a landscaping and snow removal business that later expanded into general contracting.

His father, who opened his own company in 1967, worked days building the business and drove a taxi at night to support his wife and five children.

Growing up immersed in both family and community, D’Alonzo attended Main Street School, Weber Middle School and Paul D. Schreiber High School, graduating in 1985.

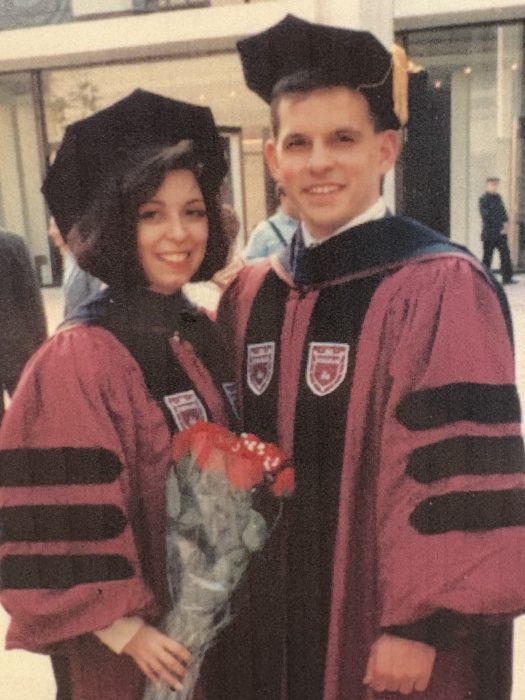

He went on to earn an economics degree from Fordham University in 1989 and a law degree from Fordham Law School in 1992.

On the first day of law school, D’Alonzo said, the dean told students to look to their left and right, suggesting one of the people nearby might one day become their spouse. At the time, he assumed it was a warning about the rigors of law school.

“He said, ‘You could be sitting next to your future spouse,’” D’Alonzo said. “And sure enough, that’s exactly what happened.”

D’Alonzo reconnected with Dina, a fellow Fordham graduate, during law school. They married soon after and recently celebrated their 33rd wedding anniversary. Dina De Giorgio later served eight years on the Town of North Hempstead Town Council, a role that would influence her husband’s eventual decision to seek office himself.

“I saw how hard it was,” he said. “And I was concerned about how ugly politics can become, especially at a local level.”

Ultimately, he said, encouragement from his wife and a desire to give back to the community where he raised his family pushed him to run.

The couple has raised two children in Port Washington. Their daughter is an MIT graduate currently pursuing advanced education, and their son is a surgical resident training in cardiothoracic surgery.

D’Alonzo said his legal training sharpened his ability to analyze complex issues, navigate regulations and make informed decisions — skills he later applied to the family business.

In his early 30s, as his father was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, D’Alonzo helped lead a restructuring of the company to ensure long-term stability and succession. He has served as president of the construction division for nearly 28 years.

Today, the family’s construction and landscaping companies employ more than 85 people and work throughout Long Island, New York City, Queens and Westchester County.

“I’m wired to solve problems,” D’Alonzo said. “Whether it’s construction, business or government, it’s about understanding the process and finding workable solutions.”

D’Alonzo said his interest in the Water Pollution Control District dates back to childhood, when he toured the wastewater treatment plant as a student at Main Street School.

As commissioner, he said his first priority is ensuring the district remains focused on its core mission: treating wastewater safely before it is discharged into Manhasset Bay.

“The health of the bay is non-negotiable,” he said. “I swim in it. My neighbors swim in it. We all depend on it.”

Beyond daily operations, D’Alonzo said he wants the district to explore long-term initiatives, including the possibility of extending sewer service to currently unserved areas over time and studying whether treated wastewater could be reused for irrigation.

Such reuse, he said, could help reduce strain on Long Island’s sole-source aquifer and limit saltwater intrusion.

He also identified Sunset Park, land owned by the sewer district and operated by licensees, as an issue requiring careful, community-driven planning.

While the district is not legally permitted to operate parks, D’Alonzo said decisions about the site should involve broad stakeholder input and a clear long-term vision.

“There’s no perfect solution,” he said. “But if you approach it thoughtfully and transparently, you can arrive at the best possible outcome for the community.”

For D’Alonzo, the role represents both a professional challenge and a personal commitment.

“This isn’t abstract,” he said. “This is my hometown. These are my neighbors. I want to leave things better than I found them.”