Talat Hamdani shifts between the kitchen and living room of her spacious Lake Grove home on a quiet Wednesday afternoon when the silence is suddenly shattered.

White bold letters highlighted by a blue streak splash across her television screen as two figures talk excitedly about developments in the dual bombing of the Boston Marathon just two days earlier. Footage of gray smoke billowing above a chaotic frenzy of police, first responders, injured runners and spectators as others run frantically for cover stream behind them in an endless loop.

Hamdani snatches the remote and raises the volume.

CNN anchor Wolf Blitzer hurriedly turns to one of CNN’s most senior correspondents, John King, who delivers the news: citing unnamed law enforcement sources, they declare there has been an arrest in the investigation, the first successful terror attack on a U.S. city since Sept. 11, 2001, killing three and injured more than 200. Police obtained video, says King, that shows a “dark-skinned male” placing a bomb near the second blast site along the Boston Marathon route.

“I pray it’s not a Muslim,” worries Hamdani, glancing back at her television.

Her fears, she says, were shared by others in Long Island’s Muslim community. Most likely they were shared throughout Muslim communities across the country. And they are justified. Since 9/11, countless law-abiding, peace-loving, family oriented Muslim Americans have been targeted, physically and verbally assaulted, spied on by law enforcement agencies sworn to protect all citizens, stereotyped as anti-Americans and even branded as terrorists. Islam itself, a centuries-old religion founded upon the universal principles of peace and love, say Muslim leaders, has become demonized due to its bastardization by those who commit the horrifying atrocities, such as the recent bombings in Boston, in its name.

Hamdani knows this all too well. A 61-year-old mother of two from Pakistan, she can relate to the extreme anguish and sorrow gripping the latest victims of Islamic extremists.

Just to her side rests a photograph of a smiling President Barack Obama, gray haired and in a form-fitting navy blue suit, his right hand on Hamdani’s shoulder. The photo was snapped in Manhattan on May 5, 2011, three days after Osama bin Laden was taken out by Navy SEALs. Hamdani’s head is tilted upward as she reciprocates Obama’s grin.

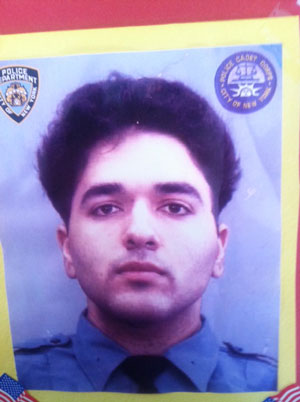

In the morning hours of Sept. 11, 2001, her son Salman was taking the No. 7 train from Flushing, Queens, to Manhattan when “he probably saw the towers burning like everyone else,” recalls Hamdani, her face for the first time devoid of tears while telling this tale. Instead of heading to his job at Rockefeller University on the opposite end of the city, Salman, a New York City police cadet and an aspiring doctor “with a very compassionate soul,” says Hamdani, voluntarily rushed toward the burning World Trade Center, never to be seen again—along with 2,700 other victims.

What makes Salman’s death even more agonizing for Hamdani, however, is what transpired soon after authorities learned he was unaccounted for.

Instead of her son’s photo ending up on a Missing Persons flier, a black-and-white NYPD handout displaying Salman’s image began circulating around the city about a month after the tragedy, stating: “Hold and detain.” Another seeking his whereabouts declared: “NYPD Police Cadet Missing Since Attacks. Joint Terrorist Task Force Seeking Him. Has Chemistry Background!!”

Then came a New York Post headline: “Missing—Or Hiding? Mystery of NYPD Cadet From Pakistan.”

Her son—a Muslim who had sacrificed his life to save others he did not even know—was wanted in connection with the Twin Towers attacks.

Hamdani, a soft-spoken school teacher who moved to Long Island from Bayside, Queens, seeking a fresh start after the death of her husband and son, has not only been speaking out to correct the public record regarding Salman (the NYPD still will not include his name on its official 9/11 Memorial for those killed in the attacks), but has also been trying compassionately to educate the public about Islam, defending her faith in the face of misperceptions and the very extremists who have hijacked it.

Her pleas come at a time when more Muslims are living on Long Island than ever before.

A May 2012 religion census report released by the Association of Statisticians of American Religious Bodies reveals that the population of those who adhere to the Islamic faith on LI has grown exponentially between 2000 and 2010—up 40 percent in Nassau and 63 percent in Suffolk.

That’s not even the total Muslim population; many Muslims, for example, do not “adhere.” Meanwhile, many LI mosques have been expanding. And there’s a good chance many of them were monitored by the NYPD during covert surveillance of the LI Muslim population after 9/11.

Hate crimes against Muslims increased after those attacks and tensions were reignited when Rep. Peter King (R-Seaford) held his Muslim “Radicalization” hearings as chairman of the House Homeland Security Committee. Since then, there have been several failed terror attacks, some stopped by sheer luck, and others the result of extraordinary work by law enforcement, including the NYPD.

The fight to dispel misconceptions gets harder with every attack and foiled plot. Making matters worse, two Long Islanders became radicalized in America and latched onto foreign terrorist groups. One of those men was an al-Qaeda propagandist from Westbury, killed by a drone missile in 2011, who was the editor of Inspire, an English-language al-Qaeda magazine, which the two alleged Boston bombers, 26-year-old Tamerlan Tsarnev and 19-year-old Dzhokhar Tsarnev, both Muslims, reportedly read.

But are terrorist extremists, essentially maniacs and murderers, truly Muslim? And should the deranged actions of a handful of sinister criminals proclaiming their association with a particular religion be allowed to define the entire faith and its 1.6 billion followers?

Hamdani, along with religious leaders from various other denominations, resoundingly declare: “No!”

“If you place a couple of dirty drops inside the ocean, it’s still the ocean,” says Sister Sanaa Nadim, chaplain of Stony Brook University’s Muslim Student Association (MSA), a support group that focuses on educational and spiritual understanding among its members, on-campus and outside communities. “How can we say all the ocean is ugly? Meanwhile, fish comes out of it, life comes out of it, so many amazing things.

“That’s the ocean of the Muslim community.”

NEW KIDS ON THE BLOCK

The sun melts the gray-blue sky over Stony Brook University into black as a crowd of about 100 students and faculty form a semicircle around one of the campus’ many water fountains for a candlelight vigil organized by the school’s interfaith center and dedicated to the victims of the Boston Marathon bombing.

Nadim, a chaplain here for two decades, gave up a lucrative career on Wall Street to devote her life to Stony Brook’s Muslim youth. She leads the prayer. Her eyes peer toward the crescent of onlookers as the colors fade, reciting Psalm 23 from the Bible then reading a Muslim prayer before offering her own words of wisdom.

“Don’t allow the terror to prevail, don’t let it make us hateful inside, don’t let the anger eat away at us,” she pleads. “On the contrary, let us defeat terror by surviving and by reaching out to one another, by building bridges with each other by educating one another on who we really are.”

Nadim raised her family on LI. Her office abuts those of other religious leaders on the second floor of Stony Brook’s Student Union building, where the campus’ interfaith groups—Jews, Catholics, Muslims and Protestants—share a narrow hallway. This corridor, filled with inspiring messages of hope even during the darkest of times, exemplifies solidarity and how all religions can come together for a shared purpose.

Stony Brook’s Muslim Student Association is the largest campus group in the nation. Its members meet every Friday for Jummah prayer, which attracts upwards of 200 students. Those adhering to the faith pack a large room adjacent to the cafeteria. Bursts of laughter can be heard from students’ filing their bellies while its Muslim community prays solemnly toward Mecca—a city in Saudi Arabia home to Masjad al-Haram, which translates into “The Grand [or Sacred] Mosque” and the birthplace of the prophet Muhammad.

This mosque encloses another of Islam’s holiest sites, the Kaaaba—a cuboid-shaped temple which includes the “Black Stone,” a glassy, dark mineral revered as a relic by the devout and believed widely to be a meteorite.

Devout Muslims are required to face Mecca during daily prayers, to be performed five times a day. They are restricted from drinking alcohol, owning a dog, are permitted to eat only specially prepared food (called Halal), must fast during the holy month of Ramadan, and cleanse their feet and hands before praying.

As is any religion, Islam is a complex faith, with varying degrees of followers.

“When you talk about the Muslim youth, every one of them has a different journey,” Nadim says inside her office, replete with photos, certificates of appreciation from local lawmakers, a Koran and a book declaring: “You’re In Seawolves Country.”

“And the beauty of this country, no matter what happens and no matter how negative the press can be, there’s good stories, there are beautiful stories of successes of Muslim young men and young women,” she continues. “And the beauty of this whole thing is that people don’t give up on themselves simply because they are disheartened about current events.”

Muslim American Long Islanders are physicians and pharmacists, students and community leaders and teachers and Imams—the worship leaders of a mosque.

Dr. Faroque Khan is the former chief of medicine for Nassau County University Medical Center. Now a board member for the Islamic Center of Long Island in Westbury, he has become the unofficial spokeman for the Muslim American community in Nassau during times of crisis. It’s not like he had a choice in the matter.

“We’ve been kind of the de-facto spokespersons for the community whether we want it or don’t want it,” Khan says from a couch inside his Muttontown home, where the concept of the Islamic Center was born. “People come asking questions, so we have to find the answers.”

“Someone hits us with a sledgehammer 8,000 miles away,” he explains, “and we have to give an answer here, so that’s been the challenge.”

Why are Muslims terrorists? Why do you guys destroy everything? What’s a woman’s role in the Islamic faith? Do you believe in Jesus? How do you reconcile the difference between church and state? These are common questions to Khan at public events, he says, with terrorism always on the top of the list.

“I can understand where people are coming from,” Khan says calmly. “Sadly, the first major exposure for American to a Muslim was 9/11, and that was a terrible introduction.”

“These are people who are claiming to act in the name of Islam, and they’re committing certain actions that most Muslims irrevocably hate and detest and completely condemn,” says Zain Ali, an Italian-Pakistani senior at SBU studying Spanish and bio chemistry, who also serves as president of the school’s MSA. “What the community needs to do, rather than be reactive, is be proactive.”

Khan, Nadim and others stress that Islam is a religion founded on the fundamental principles at the core of all major religions: mutual respect.

“It’s a continuation of the Jewish, Christian faith,” explains Khan. “We believe in all those previous faiths that have come through prophets.

“We follow all Commandments except one: Keep the Sabbath,” he continues. We don’t have a day off; it’s a work day for us. The rest we all believe… The bottom line is the Golden Rule is the same for everybody: Do unto your neighbor what you would do unto yourself. It’s the same in every faith.

“Jesus Christ is considered one of the five great prophets in the Koran,” he adds.

Muslim leaders ask non-Muslims to look deeper instead of believing everything they see and hear in the media. A February 2013 report by the Triangle Center on Terrorism and Homeland Security found that Muslim American terrorism is actually on the decline.

Thirty-three of the 180,000 murders in America since Sept. 11 were attributed to Islamic terrorism, the report states, while “more than 200 Americans have been killed in political violence by white supremacists and other groups on the far right,” according to a recent study by the Combatting Terrorism Center at the U.S. Military Academy, which the Triangle Center analysis cites.

“Obviously 9/11 has made people hypersensitive to certain types of threats, and God-forbid that something should happen on a comparable scale from the white supremacists groups, then I imagine our sensitivity to those kinds of threats would increase as well,” says its author Charles Kurzman, professor of sociology at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

But the number of deaths by Islamic terrorists could be “in the thousands,” argues Congressman King, if it wasn’t for law enforcement’s ability to thwart recent plots.

“What makes the Islamists’ threat different right now is it’s the only one right now which has an overseas component,” says King.

Investigators began questioning a “Saudi man” injured in the bombing who was identified by the New York Post as a “potential suspect” just moments after the two pressure cookers exploded near the Boston Marathon’s finish line. The paper noted that a bystander had tackled him to the ground because he was running away from the bombing and looked “suspicious.”

Just as CNN’s report blaring from Hamdani’s TV about the “dark-skinned male” turned out to be erroneous, the “Saudi man” was eventually cleared and never officially identified as a suspect.

It’s this rush to blame Muslims—dubbed “Islamophobia” by the media—that has so many law-abiding Muslims, such as Hamdani and Khan, so frustrated. They want the perpetrators called what they are—homicidal maniacs, the same description that could be used to describe mass murderers from any religious denomination.

“Now here’s the problem,” says Khan. “The same day that this is happening [in Boston], ricin-laden letters are arriving in Washington [D.C] and the person has been identified and he has been arrested.” [Charges have since been dropped against Mississippian Kevin Curtis, an Elvis impersonator and conspiracy theorist.] “And the first response coming out is he’s mentally disturbed, so why don’t you use the same principle when you talk about somebody who is crazy enough to put bombs and kill people like this? The guy is not normal; obviously, he’s either brainwashed or he’s deranged.

“Nine-eleven was a double-whammy for the Muslims,” he continues. “Number one, we lost a lot of people we knew from the community…then we became the suspects.”

“None of these [9/11] hijackers were American Muslims,” says Hamdani. “Why are we held responsible? Similarly with this [Boston] attack—whoever it is—let’s say for argument sake it happens to be a Jewish person, are we going to condemn all the Jews in this country? We will not and we have never done that. If it happens to be a Christian person, we will not condemn him for his faith. We did not condemn Timothy McVeigh [who killed 168 and injured more than 800 when he blew up the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City on April 19, 1995] for his faith.

“God-forbid it happens again to be a person of Muslim faith, it will have a negative impact,” she laments about the Boston bombings. “It will definitely have a negative impact.”

“It’s such nonsense!” blasts Nayyar Imam, chairman of the Muslim Advisory Board of Suffolk County, the Anti-Bias Task Force of Brookhaven Town and the Muslim chaplain for Suffolk County police. “I’m worried about our children. It [will be] worse before it gets better.”

The backlash against some Muslims in the wake of the Boston attacks was immediate.

A Bangladeshi man described by his attackers as a “fucking Arab” was jumped in the Bronx. A Long Island man was beaten in a mall parking lot but was saved by police officers. There have also been several incidents of people driving by hijab-wearing Muslim women and shouting obscenities, according to one Muslim community leader.

“Young people in our society need to remain calm and not respond with anger, and understand that tensions are running high,” advises a 29-year-old Long Island man who asked for anonymity because he’s been a victim of similar attacks before. “It’s our job as good Muslims to inform the public that everything will be okay: we are on their side, we are American.”

In the wake of the recent Boston tragedy, some have been clamoring for surveillance of American mosques as a way for law enforcement to deter future attacks. Yet the secret surveillance of Muslims has already been taking place throughout the city and Long Island for quite some time—including Stony Brook’s student-run Muslim association website.

EAGLE EYE

The notes scribbled on the NYPD’s Demographic Report for Nassau (2007) and Suffolk (2006) counties—a covert initiative to gather information on the local Muslim community—are vague and loaded with unenlightening observations. There are no smoking guns. The documents could very well be taken from the script of Police Academy or the law enforcement parody show, Reno 911!

Combined, they amount to 166 pages describing surveillance of Muslim restaurants, religious institutions, smoke shops and “locations of concern” in Nassau—the towns of Hempstead, North Hempstead and Oyster Bay—and three religious institutions classified as “locations requiring further examination.” The report is the spy world’s equivalent of the Yellow Pages for Muslim businesses and houses of worship, filled with descriptions of Korans, donation boxes, fliers listing phone numbers, wardrobe, stores’ capacities and presumptions about just how devout those observed were.

“We recognized one of the Bengali males in the group as a regular in the vicinity of Jackson Heights,” one undercover officer writes in his report about a Suffolk Dunkin’ Donuts—twice noting that customers were visiting the location after prayer. “Nothing of [significance] was overheard.”

Some are downright comical.

One discovery contained in the NYPD’s covert stakeouts of a kebab joint in Huntington provides the revelation that “this location also has belly dancing on the weekends.”

The program was a closely-guarded secret until the reports were leaked to The Associated Press, which earned a Pulitzer Prize for its reporting on them.

The NYPD also monitored Muslim student association groups at local universities, including the Stony Brook University MSA’s website, according to the AP, and had informants reporting from inside mosques.

“What did you get out of it?” asks Khan rhetorically. “How much money did you spend and what was the outcome? I have not seen or heard of anyone who has been arrested, prosecuted and convicted based on that spying. So for me, it was a wasted effort. What was the downside? You lost the trust of the very community willing to help.”

Both NYPD Commissioner Raymond Kelly and New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg have defended the controversial initiative, noting the necessity of preventing future attacks.

“The NYPD is trying to stop terrorism in the entire region,” the mayor said last year. “When there’s no lead, it’s just you’re trying to get familiar with what’s going on and where people might go and where people might be.”

For the NYPD, the spying may be an example of the ends justifying the means. There have been no attacks on the city since Sept. 11, and local and federal authorities have foiled several plots since then, including a plot to bomb the New York City subway system and, most recently, a plan to blow up the Federal Reserve building in New York City.

And while the NYPD may have consequently lost the trust of some LI Muslims, those same Muslims have no qualms with local law enforcement.

“They are very different: they are very open,” says Imam, comparing Suffolk police to the NYPD. Suffolk County Police Commissioner Edward Webber and Chief of Department James Burke hold several meetings a year with Muslim leaders, he says.

“We have a very good relationship,” agrees Dr. Hafiz Rehman, commissioner for the Suffolk County Human Rights Commission and an advisor to Webber and Suffolk County Executive Steve Bellone.

“It’s because of our interaction with them that they respond so quickly to our needs,” he adds.

“Was there much of a need to become directly involved [before 9/11]?” says Det. Lt. Bob Donohue, commanding officer of Suffolk police’s Community Response Bureau. “Not so much perhaps 10 years or so ago or 20 years ago…there have been some challenges we’ve faced, particularly the challenge that occurred last week in Boston…the tragedy of 9/11, but I think we have an excellent relationship and it’s because of the interaction we have with people.”

Those relationships, law enforcement officials say, are invaluable.

“[The] reality is you can’t look to have or start a relationship after something bad happens and to expect honesty and trust between people that have not had a relationship prior to that,” adds Deputy Chief Kevin Fallon, SCPD’s lead spokesman. “The fact that we maintain a very good relationship helps us in both good and bad times.”

Despite the positive gains made by Muslims in the community, suspicion remains, and they have radical Islamists abroad—and at home—to thank for that.

THE WAR WITHIN

“I am proud to be a traitor to America,” is the title of an article reportedly written by Samir Khan, an al-Qaeda mouthpiece who spent his teenager years in Westbury before moving to North Carolina.

“He’s a person who was basically raised on Long Island, became radicalized, and became a terrorist while he was on Long Island,” King said at the time.

Khan’s family grew concerned, trying several times to intervene and seeking help from religious leaders in their community, according to The New York Times. It didn’t work. Khan ended up leaving America for Yemen in 2009, and was killed two years later in a drone strike targeting al-Awlaki, an American-born cleric known for spreading anti-Western sentiment.

Bryant Neal Vinas was another Long Islander-turned-terrorist sympathizer. The Patchogue native was reportedly raised Roman Catholic, then converted to Islam before he was captured in Pakistan, and admitted to giving al-Qaeda information for a plot to bomb the Long Island Rail Road.

Imam, the SCPD Muslim chaplain and former director of the Selden Masjid, remembers seeing Vinas, or Ibrahim, as he knew him, at the mosque.

“Very quiet, very ordinary guy,” he says. “Never thought that this guy would wind up in [Pakistan] fighting against us. But that was a shocker, that was really a shocker.”

Islamic Jihad was brought back into the fold on Long Island on Sunday, April 14—one day before the Boston bombing—when blogger Pamela Geller appeared at the Chabad at Great Neck after the Great Neck Synagogue had caved to public pressure and cancelled their event.

Hundreds turned out. Some held signs declaring “No Sharia Law”—the code of law derived from the Koran—while also defending Geller’s right to free speech. About a dozen men stood sentry holding American flags along path to the entrance of the Chabad, which overlooks Manhasset Bay.

“Under the Sharia, there are blasphemy laws: you cannot criticize Islam, you cannot offend Islam,” Geller told the packed room while dozens of others watched from a screen outside. “In Muslim countries, if you blaspheme, you’re put to death. That’s the penalty for blasphemy.”

Geller’s Stop Islamization of America group was labeled a hate group by the civil rights organization, the Southern Poverty Law Center. She blasted her critics, proclaiming: “I do not promote hate speech, I expose hate speech.”

Others, such as Khan and Nadim, would disagree. But right now they’re looking toward the future—one without constant suspicion toward Muslim Americans.

COME TOGETHER

At Stony Brook, Nadim exudes pride for the country, citing Woodstock, America’s forefathers and Martin Luther King, Jr. as examples. She holds onto hope.

“I wish it didn’t happen, I wish it was a different place, a different time when people didn’t have to deal with this. I wish this young 8-year-old boy didn’t die in the way he died,” she says, teary-eyed. “I wish there is no violence. I wish there are no wars…but that’s the fact of our existence in this world. Evil is existing, together with good, and human beings have the choice to act according to evil or to act according to righteousness and good.”

The hope for a brighter future “is America,” she says. “The hope is the Constitution. The hope that every person has an inalienable right to live in peace and harmony as long as they’re law-abiding citizens. That’s the hope. And that’s what makes this country a better place than any other place.”

Hamdani also holds out hope for the future, hope that worshipers from all religions can finally see their shared common ground, hope that she, too, through her story, can transform her hardship into a tangible solution that can be shared and embraced by not only this generation, but for those yet to come.

“I’m so much at peace now,” she says, while confessing she has “one more fight to fight”—getting Salman recognized as a police cadet on the NYPD 9/11 Memorial, something the department has yet to do.

Throughout the past 13 years, Hamdani has tackled every challenge thrown her way—whether fighting for her son’s name or dispelling misconceptions about Islam. And through it all, she never lost her faith in America.

Standing proudly in front of her home, an American flag waving behind her, Hamdani is reminded about the love her son had for his country, a love so intense he laid down his life to save the lives of complete strangers.

“Nobody in this world would not want to become an American!” she exclaims. “In spite of what’s happening in the political world, I’m proud to be an American, too.”