Diane Gaines took her usual position along the pews inside Bethel African Methodist Episcopal church in Babylon.

The last few days had been a whirlwind, with Gaines taking calls from members of the community lobbying her to continue the job she had been doing for more than 15 years. Meanwhile, her own thoughts had become clouded as she nervously contemplated her future.

Gaines was in need of a sign, a gentle nudge that would help put her mind to rest. She wanted to follow her heart, but she knew the road would be turbulent and laden with pitfalls.

She wheeled herself into church that Sunday in October 2010 with her eyes wide open.

Gaines had already been through a gauntlet of obstacles. A popped blood vessel in her spine at 24 years old has relegated her for the rest of her life to a wheelchair. Then came a breast cancer diagnosis at age 40.

Gaines, a single mother of three, pushed on. Her faith never wavered. If this was His plan, then so be it. She’d accept the mission He had set forth for her.

But Gaines’ journey hit a roadblock in 2010 when the Nassau County-based Women’s Opportunity Resource Center (WORC), which she served as executive director, was shut down by its parent organization, Education and Assistance Corporation (EAC) due to a lack of funding.

For 25 years, the program helped downtrodden women who had been in and out of trouble with the criminal justice system receive vital services in order for them to effectively re-enter society, possibly earn a GED, perhaps enroll in college, and hopefully land a job, support a family. Some had been sexually and physically abused in the past. The emotional scars ran the gamut. They were drug dealers and drug abusers. Many others made a career out of petty crimes.

WORC’s mission was simple: reduce recidivism and help women climb out of a dark and lonely abyss through vocational training, educational courses, workshops, counseling, health services and emotional support.

Gaines lamented what would happen to destitute Long Island women if WORC ceased to exist. Convincing people to fund the program would be a tireless endeavor, yet something was pushing her toward reviving it.

About one month after WORC shut down, Gaines decided to stop worrying and instead put all her faith in God.

Peering at the pulpit that Sunday, Gaines recognized the youth pastor preaching that morning as the son of a WORC graduate. What some would consider a coincidence, Gaines interpreted as divine intervention.

“I can’t run from this,” she recalled.

The next day Gaines got to work. After registering WORC with the Nassau County Clerk’s office, she headed over to Fulton Avenue in Hempstead to inspect an unoccupied office space. The landlord inquired about her budget. She didn’t have one, Gaines admitted.

“I have God,” she told him.

Resistance

Gaines, who had been raised Catholic, discovered the African Methodist Episcopal church two decades ago. She made the switch after a professional mentor suggested she attend a service at Mt. Olive AME church in Port Washington—and she’s been hooked ever since.

The AME church has been in existence for more than two centuries, quietly going about its business spreading the Gospel worldwide and helping improve the communities its members call home. The first AME church was founded by a free slave in Philadelphia shortly after the official end of the American Revolution. The church’s congregation now numbers three million people—spanning 39 countries on five continents.

Suddenly the church’s bucolic lifestyle was interrupted on June 17 when bullets violently began flying inside Mother Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, S.C., the oldest AME church in the South, during Bible study. When the alleged gunman finally ended the carnage, nine lives had been lost, with the church’s venerable pastor among the dead.

Dylann Storm Roof’s motives were made clear by his venomous justification for the rampage.

“You are raping our women and taking over the country,” Roof reportedly told one of his victims inside the historic church during the slayings. On Sept. 3, prosecutors in Charleston announced they’d be seeking the death penalty.

A supposed manifesto reportedly posted on a website registered by Roof last February paints a disturbing portrait of a man painfully uncomfortable living in an America where the KKK has largely become irrelevant and hate-fueled attacks by other disciples are, in his view, too infrequent.

“I have no choice,” it reads, according to The New York Times. “I am not in the position to, alone, go into the ghetto and fight. I chose Charleston because it is most historic city in my state, and at one time had the highest ratio of blacks to Whites (sic) in the country. We have no skinheads, no real KKK, no one doing anything but talking on the internet. Well someone has to have the bravery to take it to the real world, and I guess that has to be me.”

Fueled by racism, Roof allegedly slaughtered nine God-loving people after an hour of Bible study—a common event held every Wednesday at each AME church in the country.

AME members of Long Island were just leaving Bible studies of their own when news of the bloodshed began to surface.

“I felt violated,” 64-year-old Anita Scott says inside Bethel AME Church in Freeport. Scott was raised in the AME and has family in South Carolina.

“This is my home,” she says on a quiet summer day inside Bethel. “I felt like someone had come in there and raped us…I just wonder: How can someone raise their child to hate?”

The mass murder sent a shockwave across LI, which is home to 14 AME churches—seven each in Nassau and Suffolk counties, including Bethel Copiague, where congregants will celebrate its 200th anniversary this month. LI is also home to St. David AME Zion church in Sag Harbor, a defunct AME church built in 1840 that is rumored to have been a stop on the Underground Railroad and housed a trapdoor that once hide slaves. Its pastor at the time was also a noted abolitionist, according to historians.

The AME church has always been a symbol of black resistance, says Rev. Craig Robinson, pastor of AME Bethel Church in Bay Shore. Therefore, it’s not out of the question that one of its churches would be used to hide blacks from their slave masters. (The existence of the Underground Railroad on LI has been the subject of much debate.)

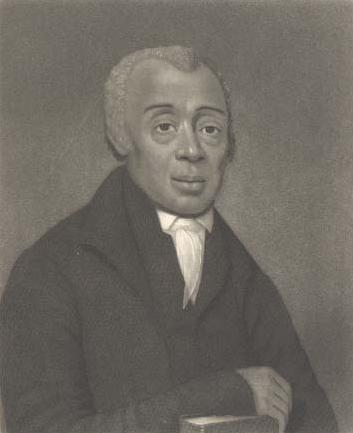

The murderous rampage on a summer evening in Charleston evoked visceral reactions and brought back memories of the church’s birth in the late 1780s (the exact date is unknown), when white Methodists insisted that blacks move to the back of St. George’s Methodist Church in Philadelphia. But it was Richard Allen’s act of defiance at the end of the 18th century that laid the groundwork for the eventual formation of the AME church. Allen, a revered black preacher and member of St. George’s, decided to lead a walkout, a pivotal moment in the history of black resistance.

Ever since Richard Allen preached his religious views to a new congregation, the AME has been at the forefront in the fight for equality. Allen, a former Pennsylvania slave, had already earned his freedom. He had become a roving Methodist preacher, touring southern states, creating a burgeoning following, and inspiring destitute slaves and free blacks alike.

Regarded as one of the country’s first black activists, Allen refused to live a compliant life. He saw the church—an independent black church, more accurately—as a place of refuge and a spiritual haven, where blacks could pray freely and speak openly, without resentful stares from white Methodists.

“The existence of the African Methodist Episcopal Church is a glaring example of black resistance to racism, to oppression,” says Robinson.

The mass murder of the “Emanuel 9” at the hands of a man allegedly motivated by his hatred toward blacks spawned yet another national conversation about America’s deep-seated racism. During his eulogy of Rev. Clementa Pinckney, the Mother Emanuel pastor and South Carolina state senator killed in the rampage, President Obama referenced the Confederate flag, revered by many in the South as a symbol of their heritage.

“Removing the flag from this state’s capitol would not be an act of political correctness; it would not be an insult to the valor of Confederate soldiers,” Obama told a packed audience in Charleston on June 26, six days after the shooting. “It would simply be an acknowledgment that the cause for which they fought—the cause of slavery—was wrong, the imposition of Jim Crow after the Civil War, the resistance to civil rights for all people, was wrong. It would be one step in an honest accounting of America’s history; a modest but meaningful balm for so many unhealed wounds.”

The shooting did more than just cause blood to spill, tears to cascade for days, and stir emotional debates on race, guns, and, most passionately, the Confederate flag. The tragedy also served as a reminder of the AME church’s vital role as a champion of black rights and as a leader in the community.

AME congregations nationwide form a tight-knit community made up of deeply devout parishioners who make it their mission to use the church to improve the lives of people in their respective neighborhoods. For decades, generations of AME members have seen racism firsthand. Mother Emanuel itself had to be rebuilt after it was burned to the ground in the 1830s amid controversy over a foiled slave revolt instigated by Denmark Vesey, one of the church’s co-founders.

“At the heart of Allen’s moral vision was an evangelical religion—Methodism—that promised equality to all believers in Christ,” writes Richard M. Newman in Freedom’s Prophet, recognized by some as the definitive biography on Allen’s life. “Indeed, one of Allen’s best claims to equal founding status was his attempt to merge faith and racial politics in the young republic.”

Visit an AME church on any Sunday and you’ll typically find a motivated congregation that utilizes Scripture and sermons as tools to better their neighborhoods. Many AME churches operate food pantries, youth groups, a women’s missionary society, health programs, Alcoholics Anonymous, and a bevy of other vital social programs. Those with larger congregations may offer more expansive services; sometimes they collaborate.

“We’re not insulated; we’re not boxed in,” says Rev. Stephen Lewis, pastor of Bethel AME Church in Freeport. “We’re bold enough to go outside and invite people.”

The AME church is constantly looking outward, says Margaret Davis, first lady of Bethel AME church in Babylon.

The AME church is “like the fueling station where you get the gasoline that you need,” says Davis. “Get pumped and go on out there and make the cycles and change lives.”

Voice of the Voiceless

The pastors who lead congregations on Long Island have traveled very different paths to get where they are now, but they all share common goals.

Rev. Lewis, the pastor at Bethel AME Church in Freeport, arrived from northern Pennsylvania. Rev. Keith Hayward, originally from Bermuda, has been the pastor of Bethel AME in Copiague for the last three years. Prior to his arrival, he also pastored a church in Pennsylvania. Rev. Dr. Lisa Williamson of Mt. Olive AME in Port Washington previously served at Trinity AME in Smithtown. Born in Venezuela, she’s grown fond of her small church on a quiet, idyllic tree-lined street in Port Washington.

Rev. Craig Robinson, 29, arrived in Bay Shore last year. The sprawling South Shore hamlet feels very much like his hometown of Ferguson, Mo., Robinson says, adjusting his tall, burly frame as he relaxes in the front pew inside Bethel AME Church in Bay Shore.

The unassuming church sits adjacent to the Long Island Rail Road tracks and is less than a block from bustling 2nd Avenue. With its vaulted ceilings and ubiquitous stained glass windows, the unpretentious 150-year-old AME house of worship evokes its humble beginnings. The ground beneath it trembles as trains shriek east and west, an omnipresent rat-a-tat often adds to the soundtrack of Robinson’s Sunday sermons.

After entering the church and getting a sense of his surrounding, Robinson called his mom back home in Ferguson and reported the eerie similarities between Bay Shore and his hometown: large groups of people struggling to get by, dilapidated cookie-cutter houses dotting the neighborhood, families scrounging for food. But like Ferguson, Bay Shore has its wealthy parts, mostly waterfront properties boasting dazzling views of the Great South Bay.

Ferguson, a St. Louis suburb, was the site of intense protests following the police shooting death of Michael Brown in August 2014. Robinson eventually moved to St. Louis, where he attended St. James AME Church. He was only 17 when he first began preaching.

In June 2014, an AME bishop appointed Robinson as the pastor of Bethel AME Church in Bay Shore. In order to be ordained, a prospective AME pastor is required to earn a master’s degree in divinity. Pastors are then appointed by bishops for one-year terms and are either reinstated or reassigned to a different AME church, perhaps in another state. Pastors never know if they’ll lead a church for more than a year.

As with anyone coming into a new neighborhood, the pastors try to ascertain the makeup of the community and the issues people face. Robinson realized quickly that the church’s food pantry helped shine a light on families stricken by poverty.

The issues facing other communities are not much different.

When Williamson arrived in Port Washington she realized there was an affordable housing problem. The pulpit provides Williamson with a powerful megaphone that allows her voice to be heard, but it’s her ability to go outside the church and speak with community leaders and public officials that helps bring issues out of the darkness and into the sunlight.

“Every good preacher should have a Bible in one hand and a newspaper in the other hand,” Williamson says.

When a member of the Port Washington Police Department unfurled a Confederate flag outside his house on the Fourth of July holiday, Williamson invited members of the community and the police commissioner to the church for a frank discussion on the flag’s presence in their neighborhood, which attracted a small but passionate group.

“A lot of the people went to school with him,” Mt. Olive AME member Edith Hall tells the Press. “They felt really hurt because they knew this officer.”

“I don’t think they fully understand what that flag represents and that’s something we did at that meeting,” adds Williamson. “One young woman gave the history [of the Confederate flag], and through the history she explained why when we see it, all these emotions come up. If I see a Confederate flag my impression is you do not care for me as an African American.”

Among her duties, Williamson says, is establishing a working relationship with the Port Washington Police Department, which is headquartered less than a mile south of Mt. Olive.

“As a pastor, we know you have to establish a relationship with law enforcement, unfortunately because of the history,” Williamson tells the Press.

“Social justice, community activism,” she adds, “that’s what we were borne out of. And with the climate in the country now, we’re even getting ready to do it on a much larger scale.”

Long Island has a long history of racial tension. One of the largest KKK rallies outside the South took place in Nassau in 1922, according to The New York Times. Two years later, some 30,000 spectators watched 2,000 robed Klansmen parade through Freeport. Those unresolved issues linger on today.

A report published by the Syosset-based nonprofit ERASE Racism in January found that LI remains one of the most segregated regions in the country, with “segregation between blacks and whites remaining extremely high and segregation between Latinos, Asians and whites increasing.” The same report also noted that only 3 percent of black students and 5 percent of Latino students have access to the highest performing schools in Nassau and Suffolk counties, compared to 28 percent of whites and 30 percent of Asian students.

There’s also the ongoing issue of affordable housing. Last year, the US Department of Justice filed a lawsuit against the Town of Oyster Bay, alleging that it violated the Fair Housing Act by giving preference to residents of the town, which is majority white. That same summer a Mineola landlord agreed to a $165,000 settlement in a case in which he was accused of discriminating against blacks. Two nonprofits, including ERASE Racism, sent both black and white “testers” to the complex and had them inquire about vacancies. The black tester was told there were no rooms available, yet four hours later the white tester was shown an available one-bedroom apartment.

AME pastors relish the opportunity to be more than just religious leaders confined within the walls of their church.

“I came with this mindset: I was not sent to just pastor Bethel church, I was sent to pastor this community,” says Hayward, who was assigned to Bethel AME in Copiague in January 2012.

Pastors like Hayward say they’re following the path forged by Allen more than two centuries ago.

“If there’s legislation in this community that is not for the holistic healing and development of people, you will hear my voice,” Hayward says recently from across a large brown desk inside his spacious office at Bethel AME in Copiague. “If the school district is not providing our children the holistic education and the procedures and protocols are not correct, they will hear my voice.”

‘To Strengthen Those Things That Remain’

Celebrating its 200th anniversary this month, Hayward’s church does everything from holding toy giveaways and fundraisers to hosting Alcoholics and Narcotics Anonymous meetings on Wednesdays, running a weekly GED program in partnership with SUNY Farmingdale, and a two-hour seminar about diabetes every Tuesday for six weeks in the fall. And that’s not all.

Hayward is especially proud of the “Fatherhood Initiative,” which he instituted upon his arrival in Copiague. The six-week program reconnects troubled fathers with their children following a protracted separation, perhaps due to incarceration or a frayed relationship, whatever the reason. The results have been “phenomenal,” so far, Hayward says with pride.

“Some of the men have been back here on a Sunday morning and have had their children with them,” he says. “Even the mothers of the children are more appreciative of the fact that the fathers are more engaged in their children’s lives.”

Hayward always keeps his ear to the ground. The pastor recently learned of an illiterate 9-year-old boy.

“That was grievous to me,” he says, struggling to hide his displeasure. Hayward immediately set a goal to have the child reading before classes resumed this fall.

The child had slipped through the cracks because of troubles at home, but the church stepped in to fill the void that the school district had been unable to.

“He’s not at the point where we can’t reach him,” Hayward says.

Hayward could very well be the unofficial mayor of Copiague, and Bethel AME its city hall. His influence is everywhere: the county legislature, judicial system, police, school districts, neighboring businesses (Toys ‘R’ US donates to the church). Bethel AME now has 325 congregants, up from about 100 before Hayward was appointed pastor. Bible study attracts on average 110 people each week.

Hayward’s church was initially founded in Amityville in the 19th century but has since moved to neighboring Copiague. The church still owns its original property on Albany Avenue as well as an adjacent cemetery, where the last burial took place in 1897, he says. These days the parcel where the original church once sat is vacant but the community takes advantage of the open space for recreational activities.

There’s a piece of Scripture in the Book of Revelations that Hayward lives by: “To strengthen those things that remain.” In Hayward’s case, it’d be the community that he’s hoping to uplift.

“I base my ministry on that one Scripture,” he says.

It’s social outreach projects like these that are happening all the time at AME churches across the Island.

At Bethel AME in Freeport, Lewis speaks proudly of “Joshua Generation,” a program designed to reach young people in the community. More than 50 youngsters visit the church on Friday nights, he says, “because, really, they have nowhere else to go.”

Instead of roaming the neighborhood, they take part in physical and educational activities, participate in Bible study, and, if someone in the community has been generous with donations, travel to sporting events in the area.

“We keep them involved,” Lewis says.

AME’s faithful take pride in the work they do outside the church.

Diane Gaines was able to re-establish WORC in 2010, using her savings to pay for rent in Hempstead and reaching out to members of the church and public officials for support. She was able to secure thousands of dollars in funding from the AME church through a Women’s Missionary Society program dubbed “Project Possible.”

Several years ago, then-Nassau County District Attorney Kathleen Rice provided WORC, which was renamed The Woman’s Opportunity Rehabilitation Center, with a $20,000 grant from the office’s asset forfeiture fund—money seized during investigations. That number jumped to $50,000 last year, Gaines says in her fourth floor office along Franklin Avenue in Hempstead.

Gaines is sitting in her wheelchair, her phone constantly ringing and the sound of students and volunteers scurrying in and out. It’s a busy Thursday morning in late August at WORC. The small group of volunteers is hastily preparing for an event at the African American Museum of Nassau County, the only such museum in the Northeast, where acting Nassau County District Attorney Madeline Singas will be on hand to award WORC a $55,000 grant.

Gaines wheels her way through the museum across the street and gazes at the crowd. The room is lined with enlarged U.S. Postal Service stamps of prominent blacks. There’s one of Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, Ella Fitzgerald and Rosa Parks. Judging by the celebrity-like reaction she inspires from friends and admirers, Gaines could one day bless that very same wall.

“Anyone who meets Diane can’t help but be impressed by just her enthusiasm and her advocacy and her passion and commitment to women,” Singas tells the crowd of about 30 people. “It’s contagious.”

The DA’s office is in the unique position of trying to help the very people it’s supposed to prosecute—that is, coordinating with the criminal justice system to provide alternatives to incarceration to women charged with low-level offenses.

“We think of our office as a place where we can be sort of proactive,” Singas tells the Press. “We put a lot of our money into crime prevention, so a lot of these programs with women and younger offenders and young children—they have to pay their debt to society but at the same time they don’t have to wear this as a stigma for the rest of their lives.”

Aside from helping women who previously have been incarcerated, WORC often takes in women—with the help of the DA’s office and Nassau County judges—as an alternative to incarceration.

“I’ve seen lives changed,” Joyce Lewis, an AME member and WORC volunteer, tells the Press.

Students who previously looked lost now “have a shimmer of hope,” she says, adding: “Selfishly I would like to see fast growth, but I’ve seen seeds planted, I’ve seen hope, and I’ve seen the chance for a change.”

“I know this is the work that God called me to do,” Lewis beams.

Much of the credit goes to Gaines, WORC volunteers and former students say.

“My life has changed dramatically because of the WORC program,” says Victoria Roberts, who graduated WORC after a 13-year battle with drugs and now works as Nassau County’s Reentry Coordinator, which helps individuals get back on their feet after state incarceration.

At one point, Roberts was homeless, out of work, and lost her two kids to foster care. She’s fought tirelessly since. She turned her life around, got her children back, has a home.

“I owe it all to Ms. Gaines,” she says of her success. “She [has] three daughters but she has a multitude of daughters. There are many women who can stand up here and tell stories similar to mine and we owe it all to Ms. Gaines.”

When Wendy Priester first met Gaines she was a mess, battling anger issues. After one day at WORC she told Gaines not to expect her back. She ended up returning the next day.

Gaines helped her find a part-time job, she tells the audience, tears streaming down her cheeks. Finally, everything started falling into place.

“I’m about to buy my first house,” she says, the room erupting in applause.

With tears surging and her voice cracking, Priester turns toward Gaines and leans in for a hug.

About a dozen AME members are in attendance, many of whom are WORC volunteers.

Gaines asks them to stand up to be recognized for their work.

She then asks a man named Johnny to sing one of her favorite songs. He doesn’t hesitate.

“I won’t complain,” he sings, as his voice begins to soar. “Sometimes the clouds hang low. I’ve asked the Lord why so much pain. He knows what’s best for me. These weary eyes, they can’t see, so I’ll say, Thank you, Lord! Thank you, Lord! I won’t complain.”

It’s easy to understand why Gaines chose that song.

“She’s such an inspiration,” says Jacqueline Watkins, 72, of Amityville, another AME member. “I’ve never heard her complain. Always positive. I lost my husband just about three years ago; she was always encouraging to me.”

Gaines, who is affectionately known as “Ms. Gaines,” credits her faith and the AME church.

“I just believed that this was a mission from God,” she says, back inside WORC’s Hempstead office. “That God wanted me to do this.”

“I would not have re-established the WORC program without my faith,” Gaines says, reflecting on that life-changing Sunday at Bethel AME in Babylon.

“It’s my faith that keeps me going now.”

It’s that faith AME members turned to on the night of June 20.

Faith and Politics

The Sunday following the Charleston slayings, Rev. Robinson stood at the pulpit with a heavy heart and raised a litany of questions swirling through the minds of millions of members worldwide:

“Why did it happen?”

“Why that church?”

“Why such violence?”

“Why such hate?”

“Why?”

To find the answers, Robinson says that all one has to do is peer into America’s past.

“For what we have witnessed in the massacre at Mother Emanuel is in my estimation history’s chickens coming home to roost,” he told his congregants.

“We have seen this before in the treatment of slaves on Southern plantations,” he added. “We have seen this before in the bodies that were lynched and mutilated and burned from America’s inception up into the early parts of the 20th century. We have seen this before in the removal of Africans from their motherland, in the removal of Native Americans from their ancestral land, by force if necessary… We have seen all of this before.”

Robinson was conducting Bible study the evening bullets rang out inside Mother Emanuel.

One glance at his phone afterward prompted a whirlwind of emotions: first confusion and disbelief followed by extreme anguish.

As he absorbed all that had transpired that evening, Robinson couldn’t help but recognize the feeling that was sinking in.

“I think I felt the same way about this that I did with Trayvon Martin,” Robinson says. “I think it’s just the pervasive presence of violence against the black community, black bodies, black institutions.”

“And so you both have a deep emotional connection with all of it,” he adds. “Whether it’s Trayvon Martin or Eric Garner or any of those people, you feel a sort of personal connection. But then you also have a somewhat sort of numbness to it because you’re very clear of the history that much of this violence is rooted in. And so…you’re sort of lamenting, you’re sort of calling God into question publicly as well as praying for hope.”

The self-effacing pastor portrays a calm demeanor amid heightened tension in black communities. Robinson has preached about the deaths of Michael Brown, Eric Garner, and Akai Gurley, as well as the tragic slayings of two NYPD officers fatally shot in an ambush last December, which further inflamed the political discourse. His sermons are a collection of current events woven within Holy Scripture reflecting God’s will.

“The shooter had much to draw on as material for how he would dispense his brand of hatred,” he tells his congregation. “And if we are going to move forward from this together, people of all walks life, all ethnicities and races must come and talk truthfully about these issues and facts. The fact that America, in all its ideals, has an underside, and that place has been where the oppressed, including many in the black community, have found themselves for centuries.

“There are tons of raw material for our shooter to draw on,” he continues. “But there are some deeper issues than just our history. The other question that comes up in my mind is: What happened to his heart? What happened to make this man so callous in the execution of his mission? What happened that made him forsake the voice of reason and good, the voice that told him not to shoot because these people were so nice to him? What happened to his heart, his compassion, his basic humanity?”

Robinson has a lot to say, even when the pews are empty.

“Like in most of these places, whether it’s Charleston or Bay Shore or Ferguson, the issues far predate anybody that has the wherewithal to try to change it,” Robinson tells the Press. “When you’re talking about a Confederate flag, even though the Confederate flag has a bunch more recent history, you know, you’re talking about a history of racism and slavery and the dehumanization of an entire group of people that spans 300 years. You can’t just undo 300 years of history.”

Rev. Hayward agrees.

The pastor was traveling on the New Jersey Turnpike when news reports of the horrific slayings came through his radio. Two hours earlier, Hayward was also teaching Bible study.

“That hit me in a way that I’ve never felt,” Hayward says of the bloodshed.

He talks about a persistent “racial divide” in the country, how when Africans were taken from their homelands they were transformed into slaves. He recalls the time Richard Allen was told, “You’re no longer allowed to pray at this altar.”

Still, he keeps his faith.

“So, when this young man set out to do evil, God has turned it around for good,” says Hayward. “He has brought people together in South Carolina that had not embraced each other before.”

Hayward may take his cues from God, but he finds inspiration in how people have reacted since the shooting.

The number of people who attended Bible study at Mother Emanuel skyrocketed to 250 in the weeks after the attack, he explains.

“Love wins,” he says.

People who never had shown interest in the AME church have now become members, Hayward says.

“Love wins,” he repeats.

“The church was born out of racism, Mother Emanuel the struggle and challenges they’ve been through was out of injustice and racism,” Hayward adds. “Bethel Church in Copiague dwells in a community that has racial divide and hate. I’ve met some phenomenal Caucasian men and women on this Island that have become good friends—there’s another side to this. Love wins.

“When we show love, we produce love,” he continues. “I think that what we need to do is look at the value of individuals. What if God treated us the way we treated ourselves? But because he doesn’t, love wins—every time.”

Similarly, Rev. Williamson of Mt. Olive in Port Washington went to church on the Sunday following the massacre planning to deliver a message of hope. Peruse the Bible and you’ll find something in the text that helps you find a way to overcome tragedies, she says.

Williamson is not surprised that a half-century since the Voting Rights Act and Civil Rights Act were signed into law that blatant racism still exists.

The AME church was born out of racism, she says, echoing Hayward, therefore it knows how to respond to hate. And it will continue do so, whether it’s inside the hallowed walls of its churches or at community forums and at demonstrations.

“What we’re doing now,” she tells the Press, “is we’re responding in a much more organized and political way: to say after the cameras are gone and it’s no longer a headline story, we’re still going to hold this nation accountable to 42 million of its citizens.”