A prominent civil liberties group wants the federal government to open up about a controversial anti-extremism program it fears disproportionately targets Muslim Americans.

Officially established in 2011, the so-called “Countering Violent Extremism (CVE)” initiative has been criticized for unfairly targeting Muslims, which has the adverse effect of stigmatizing an entire community based on their religion, activists say.

Now the American Civil Liberties Union is suing the government in Washington, DC federal court to get some answers.

The free speech group said it was compelled to act because the government has so far refused to release information about funding, training, and whether important privacy safeguards are in place to act as a firewall against civil liberties violations.

“For well over a decade, programs and policies like these have sent a very powerful message: When it comes to American Muslims, our nation’s actions often do not match the principles of equal treatment and religious freedom enshrined in our Constitution,” said Hina Shamsi, director of the ACLU National Security Project, in announcing the lawsuit.

In its lawsuit, the ACLU argues that there’s been “scant information” made public about the program.

“The premise of federal CVE programs is that the adoption of extreme or ‘radical’ ideas places individuals on a path toward violence, and that there are observable ‘indicators’ to identify those who are ‘vulnerable’ to ‘radicalization’ or ‘at risk’ of being recruited by terrorist groups,” the group notes in the suit.

The government, the suit adds, has not “publicly disclosed any scientific or other evidentiary support for this premise.”

Under the Obama administration, the government has implemented several CVE-related initiatives over the years, including a highly publicized summit last year to discuss the issue, a recently unveiled anti-extremism website, and pilot programs in three major US cities intended to target radicalization.

The ACLU argues the pilot program in particular—which was first installed in Boston, Los Angeles, and Minneapolis—is aimed “almost exclusively” at Muslim American communities, a potential infringement on residents’ freedom of religion rights.

Among the defendants are the Department of Homeland Security, FBI, Department of Justice, and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence.

What has some activists so concerned is the government’s apparent outsourcing of law enforcement duties to the general public by asking community leaders, social workers and even teachers and students to identify potential hallmarks of extremism and report perceived radical behavior to authorities.

“Our best defenses against this threat are well informed and equipped families, local communities, and institutions,” the government argued in its “Strategic Implementation Plan” published in December 2011.

Some of the purported signs of radicalization established by the government resemble normal human behavior, such as isolation and falling into a state of hopelessness. Essentially, communities are being taught to identify those factors in people—presumably Muslims—and notify law enforcement, the ACLU argues.

“These are all hallmarks of the human experience, and include constitutionally protected speech and conduct,” the ACLU said. “But CVE programs view them as suspicious. In effect, these programs police Americans’ ideas and beliefs.”

The suit comes a week after President Obama visited a US mosque for the first time in his presidency. The president used the platform to condemn the rise in Islamophobia and attacks on mosques and Muslim citizens.

But, as the Press noted at the time, Obama’s policies—including promoting CVE—reveal a complicated relationship with the Muslim community.

Obama last March held a CVE summit at the White House that advocacy groups said skewed toward Muslim radicalization despite studies that showed law enforcement expressed as much concern with right-wing extremists than it did with Islamist radicalization. These groups also pointed to stats that showed more people having died as a result of right-wing extremism than Jihadist violence since the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks.

But in recent months the perceived threat posed by Muslims Americans has increased after the rampage in Paris that killed 130 and the December shooting in San Bernardino, Calif. that killed 14 people. Anti-Islam sentiment has been one of the storylines of the presidential primary race thus far, and has, at least in the Republican field, reignited the debate around torture and spawned chest-pounding remarks about the extent to which candidates would go to destroy groups like ISIS.

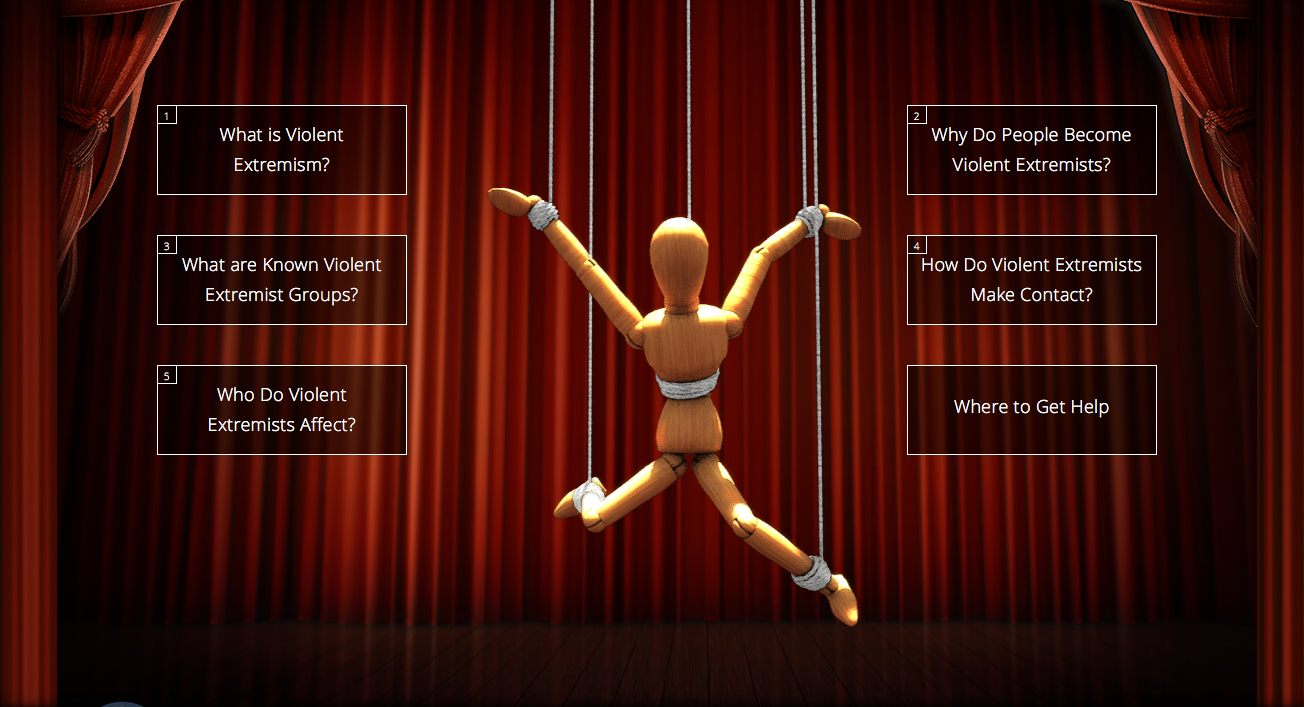

Eight months after the White House CVE summit, the FBI was supposed to unveil a long-awaited website dubbed “Don’t Be A Puppet,” dedicated to countering violent extremism, but delayed its release. It has since been published.

The site, which depicts a mannequin dangling on a stage, allows a user to explore five sections, such as “What is Violent Extremism?” with the prize at the end being an FBI certificate. The site was reportedly designed as a tool to help teachers and students in American schools identify people vulnerable to extremist ideology.

Five years removed from CVE’s unveiling, “The American public has a compelling need to understand how CVE plans and policies are being implemented, who and what they target, and what consequences they have for Americans’ privacy and civil rights,” the ACLU says.