Born and raised in Kandahar, Afghanistan, the birthplace of the Taliban, and born into a strict religious family whose history spanned 20 generations of Imams, Latifa Woodhouse always had a vision of liberty and justice and especially equality for all women. And, it was her family that instilled these values in her.

Woodhouse, now living in Great Neck for the past 25 years, is a dedicated leader at the Unitarian Universalist Congregation at Shelter Rock (SRUU). Her quest for human rights and women’s equality brought her to the SRUU where she is active on just about every social justice committee.

Woodhouse’s father was a very well-known religious and community leader in Kandahar. The thought of any of his children disobeying religious norms was unthinkable. Fortunately, her father had progressive values when it came to education and took the liberty to send her to secular school at age 4. But when she turned 11 years old, her father said she must now wear the burka to school or be tutored at home.

Woodhouse rebelled. She lost that battle and reluctantly donned her burka everyday to school. “I was sad, I was angry, I was embarrassed,” she said. “It took me at least two months of back and forth debates, tears, a lot of hardship to accept the fact.”

Wearing the burka made her feel different from the rest of the students, as most of the girls in the secular school did not wear burkas. But that changed when she met an Indian woman with young children who lived very near the school. The woman knew that Woodhouse spoke English as well as Persian, Arabic, Farsi and Urdu and wanted her to teach her children English. Woodhouse made a deal with the woman. She would teach the children English before school started if she could leave her burka there and change into regular clothes for school.

“That was like the best door open to me, to my freedom…but in the meantime I was living two lives. I was scared.”

At home, Woodhouse was not allowed to go out or visit other people’s houses. While she was feeling good in school, being around other girls and enjoying learning different things like playing volleyball and not wearing the burka, she was also angry and sad to be living two lives and lying to her parents.

“I was not happy with that but I saw the light at the end of the tunnel,” she said. “I learned through that experience that the more you get educated, the more your eyes open.”

But it was her father who had the most influence on her education and her interest in social justice. “He was very much of a community person but his mind and heart were at the right place for social justice,” she explained.

The marriage of Woodhouse’s parents was an arranged one. Her mother was 13 and her father was 22 when they got married. Her mother gave birth to Woodhouse a year later at age 14. Woodhouse was the oldest of 10 children. Women in her culture were confined to the kitchen and serving the extended family. “That was another cause why I became such a feminist at heart and soul to fight for women’s rights,” she said.

Woodhouse was taught to see life through a social justice lens. She describes stories handed down by her grandmother about kings and queens and the unjust treatment of their subjects and what people like Woodhouse could do to make the world a more equitable place. So it is no surprise that she got a job in Kabul teaching American Peace Corps volunteers the Persian language. It was there that she met Colin Woodhouse, a Peace Corps volunteer and a professor at the University of Kabul. They soon fell in love but had to keep it secret, as this would be very improper for an Afghan woman.

While teaching English at the Peace Corps, Woodhouse was offered a Fulbright scholarship in 1977 to the University at Albany. Colin had already returned to New York so this seemed like a perfect situation.

When she arrived at the airport Colin presented her with a bouquet of roses and asked her to marry him. Although she loved him, this created unforeseen complications for Woodhouse, being in a new land with academic responsibilities and now a marriage proposal. And then there was getting consent from her father to marry the man she loved in America.

The Fulbright scholarship, a cultural exchange between two countries, meant that Woodhouse must return to her home country upon completion of the scholarship. So they decided to quietly marry five days before Woodhouse was to start at Albany and kept it a secret.

Once she received her Master’s degree from the State University of Albany in English as a Second Language (ESL), she was required to return to Afghanistan. But Woodhouse’s persuasive ways convinced her advisers to allow her to stay here and teach ESL to newly arriving immigrant students.

After five long years of applications, fees and interviews, Woodhouse became a U.S. citizen. Right away she got a job teaching ESL at the University of Bridgeport, the start of a long and meaningful teaching career.

In 1979, the Russians took over Afghanistan. Life has never been safe or peaceful for the Afghan people since, according to Woodhouse. Many of her family members were executed and her father, being a public figure there, needed to escape. With the help of the U.S. government, the World Church Services and other faith institutions, Woodhouse and her husband were able to sponsor 14 members of her family to come to the U.S. in 1980.

“So thanks to the U.S. government, in many ways I am still grateful to this country and the freedom that it provides, they sent an immigration officer there…and then all of my family was interviewed and they were given immigration status, refugee status, and they came here,” Woodhouse said.

Woodhouse and her husband welcomed their extended family into their small Ohio home along with their three children at the time. Soon word got out to the Muslim community that her father was here in the U.S. and being a well-known public figure, he was invited to be the Imam of a new mosque in Flushing, which he accepted.

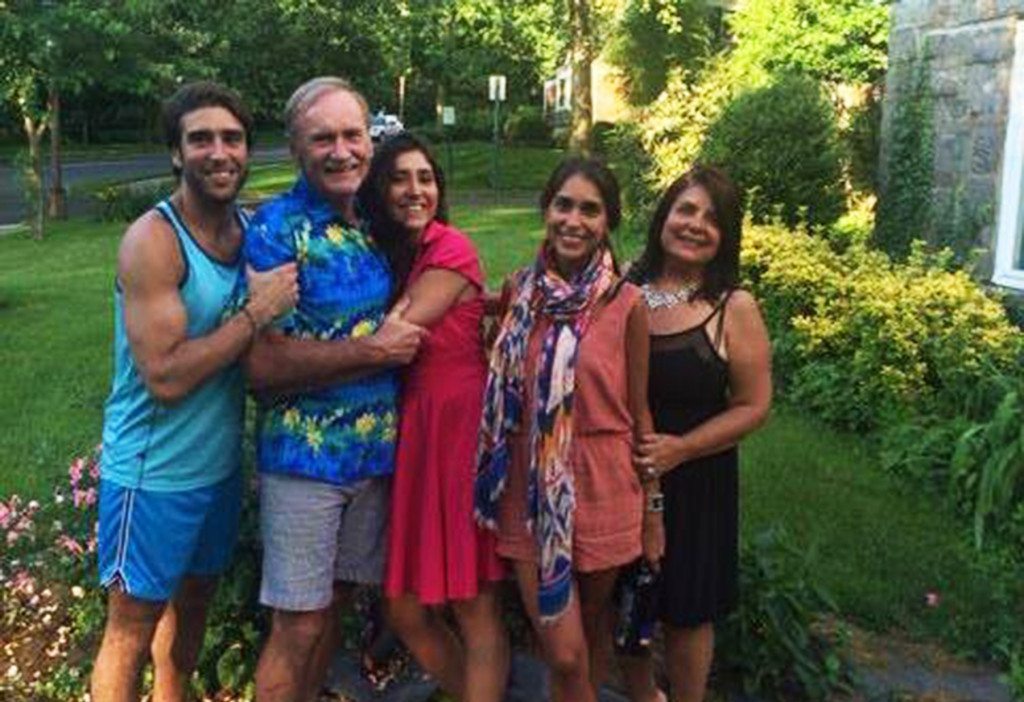

Woodhouse and her family eventually made the move to Long Island where she taught ESL programs since 1985. She and her husband and five children moved to Great Neck in 1991.

“I never felt when I first came that I am an immigrant. I felt like I was part of the whole thing,” Woodhouse said. She would involve her students in all parts of American life by creating orientation courses teaching them how to live in American as their new home but never to forget their first home.

Woodhouse and her family joined the Unitarian Universalist Congregation at Shelter Rock when her children became curious about religion. She heard about the congregation and immediately knew this was the spiritual place for her family.

“I grew up as a daughter of an Imam and I know what Islam taught us. Islam is peace, Islam is love, Islam is brotherhood and sisterhood,” Woodhouse said proudly. “So, let’s embrace the Muslims in America, the Muslims in the world, who want to bring peace, love and acceptance.

“When we come as immigrants to this country it’s like you take a branch from a tree that’s already planted and if you water and nourish that branch that will grow and give you fruit to your society,” she said. “But if you don’t pay attention to their holidays, to their interest, to their country and make them more important in your society then that branch will dry and die.”

Woodhouse believes that peace will only come by acceptance, by reaching out to those who need you. “I hope that we, as citizens of the world come together, accept one another, love one another and appreciate who we are and create the circle of peace and love. We are all one race and we are all children of God,” she said.

So in January, Woodhouse was off to Lesbos, Greece to help the vulnerable; to offer hope and refuge to those in need.

Maryann Sinclair Slutsky is the executive director of Long Island Wins, a communications organization promoting common-sense policy solutions to local immigration issues. The views expressed in this column are not necessarily those of the publisher or Anton Media Group.

Maryann Sinclair Slutsky is the executive director of Long Island Wins, a communications organization promoting common-sense policy solutions to local immigration issues. The views expressed in this column are not necessarily those of the publisher or Anton Media Group.