The convergence of New York City’s growth after the Civil War and the proximity of Port Washington’s sandbanks, the largest east of the Mississippi, led to the sand mining industry, which moved 140-million cubic yards to build the city’s skyscrapers, bridges and highways. The arrival of immigrants in the late 19th and early 20th century further facilitated those operations by supplying workers to mine the sand.

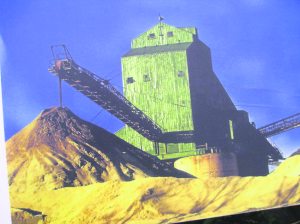

These days, when driving along verdant West Shore Road from Beacon Hill south towards Roslyn, it is hard to visualize a landscape of sandy cliffs, barren acres and massive equipment. It was not a pretty sight. For over 100 years, large sand mining operations flourished and easy access to water transport to the city enhanced their growth. The sand was not the fine sand of south shore beaches but was coarse with diverse grain sizes, which, when packed together, made excellent concrete. Developers specified Cow Bay Sand in their building contracts because of these characteristics. It was used in the Chrysler Building, the Empire State Building, the Queensborough Bridge, the FDR Drive and the West Side Highway as well as countless other buildings, streets and sidewalks. The sandy vistas were also used for more artistic applications such as backdrops for old movies like The Perils of Pauline.

In the early days, workers moved sand with wheelbarrows, but soon mechanization leveled the land more rapidly. The work was difficult and dangerous, causing serious accidents and cave-ins. When digging into the cliffs, torrents of sand would fall, threatening to engulf the miners who ran for their lives. In 1910, wages for a 12-hour day were $1.50. Sand was moved on conveyor belts to processing centers where it was washed, crushed, screened and tunneled under the road to be loaded on barges in Hempstead Harbor. In 1908, there was a strike by workers seeking to join a union. They were unsuccessful. In 1938, workers struck again. The owner of the Colonial Sand & Gravel Company, Generoso Pope, and the strikers reached an agreement and joined the AFL. There were other companies mining in the Soundview area, Manorhaven and Bayview Colony, but the West Shore operations were the largest. At its peak, 1,000 workers were employed on our peninsula and 50 barges a day were filled with sand and gravel. The last company to mine here was Roanoke Sand & Gravel, which ceased operating in 1989.

Workers expressed pride in their work. One praised the quality of the sand as “having a life,” and another said, “We did it with passion because we knew we were helping to build New York.” Some unmarried men lived in barracks while families had small houses, a few built on stilts. They shopped nearby at Langone’s and Marino’s stores. Their children attended the Hempstead Harbor School, where first to fourth graders were taught between 1916 and

1930. People expressed a fondness for the camaraderie of the tiny community. Most were Italian and shared a language and a culture.

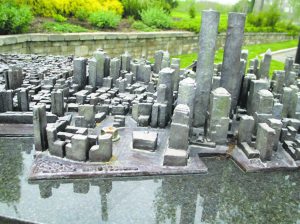

In 2011, the Sandminers Monument located on West Shore Road was dedicated to the workers and the industry that helped make New York great. Within the monument’s roadside park there is a statue of three workers standing on top of the opening to the only remaining tunnel. The original tunnel gate was refurbished by Carmine Meluzio, who worked as a maintenance welder when he first arrived from Italy in 1962. Edward Jonas, a well-known sculptor, designed an impressive tableau featuring a large hand from which sand is descending on a miniature Manhattan with replicas of hundreds of buildings, including our beloved Twin Towers, which were constructed with Cow Bay sand.

Information about the operations, its owners and workers is displayed on large panels within the park. Paving stones bear the names of workers. Those names are recognizable to many of us as their descendants still live in Port. A quote attributed to an early Italian immigrant tells a story in itself and truly applies to the sand miners: “First, the streets aren’t paved with gold. Second, they aren’t paved at all. And third, you’re expected to pave them.” The monument is a tribute to the miners who helped pave the streets and transform a city.