Permit fee amnesty law also passed

From butterfly habitats to rabbi habitations, the Nov. 7 meeting of the Village of Great Neck Board of Trustees provided village officials and attendees with an array of topics.

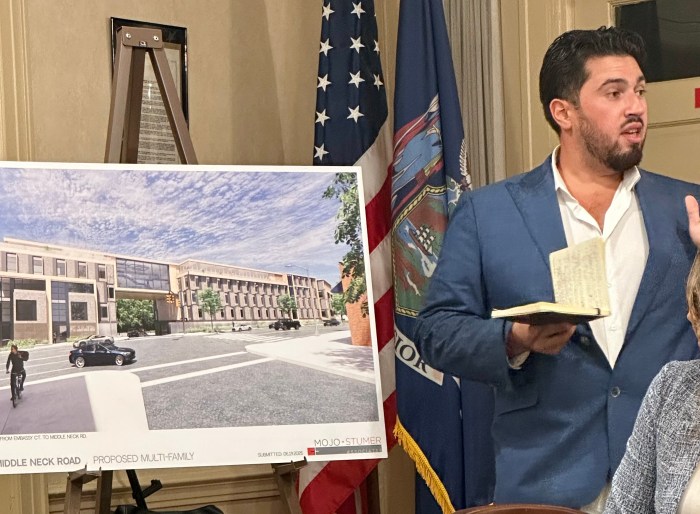

Marwa Fawaz, a senior project manager with VHB, a planning/design firm whose Long Island office is based in Hauppauge, talked about the Middle Neck Road Corridor Study.

The board unanimously voted to raise the firm’s compensation from $10,000 to $100,000 to complete the study.

According to Fawaz, this change in the scope of services will include drafting a master plan and proposed zoning amendments, along with generating a generic impact environmental statement (GEIS).

“The draft plan will include recommendations for uses, the limitations on height, bulk and setbacks, specific design guidelines to support neighborhood comparability, necessary infrastructure improvements and provision for public spaces,” Fawaz noted. “There needs to be a vision for the corridor.”

Resident Rebecca Rosenblatt Gilliar used the ensuing public comment session to raise objections to the costs and use of the consultants. She related that in 2003, using residents’ input, the village had created a “beautifully conceived” master plan “put together by people who live here and know the community.”

Mayor Pedram Bral, who defeated Gilliar in the recent election, told her, “In order to do any rezoning, you do need a consultant to come in and give us input. That does not take away the input that the public can have after [the consultants] come in and give us the presentations.”

He noted that the master plan from 2003 was outdated due to developments like the Internet, and besides, it “had gone nowhere. It is extremely difficult to have a master plan without professional supervision,” Bral pointed out.

“You don’t have to take the 2003 plan into account,” Gilliar argued. “[What you’re doing] is putting the cart before the horse. You don’t know what the community wants. You’re going to impose on the community what the consultants—”

“Again, I think you misunderstood,” Bral interrupted, emphasizing that residents would have their say after the professional master plan and recommendations are presented.

“The decision you made tonight,” Gilliar charged, “was to remove every restriction and covenant that had ever been put in place by the Board of Zoning Appeals since 1995—they’re all wiped out….The people in this community don’t have a say in what’s going on.”

The mayor assured her that he would take her words into consideration.

Path to Compliance

The board also voted unanimously to add a provision to the code to essentially give a permit fee amnesty to people who have done any type of code-compliant home project that needs building department approval and have not sought such permits. The amnesty period will run from when the law is filed with the state’s Secretary of State until Jan. 1, 2019.

The amended code carries a provision to waive doubling and even tripling the fees for any work completed prior to the filing of a completed application for a permit. However, the fees will not be waived if the applicant has received a notice of noncompliance from the building inspector.

Under village law, the board can waive the fees if the applicant can show that the project “was so minor that the tripling of the fees would be so substantially out of proportion to the additional work to the [building] department that it would amount to an unwarranted penalty, or that the performance of such work prior to the issuance of the requisite permit was reasonably necessary to save life or property, or for any other reason.”

Bral said the purpose of the change was “for people who had not received a notice of violation to be able to come to [village hall] and ask for a permit and try to legalize [any work] if it was done legally.”

He added, “The reason we are doing this is because we’d like to ensure safety. There are situations that can possibly create unsafe areas in people’s homes. By releasing the applicants from paying double or triple the fines, we hopefully encourage everyone to show up and get the proper permits to legalize their [projects].”

Trustee Bart Sobel noted that the law applied to not only “things like extensions and basements and attics. It might be for plumbing work. You might have done your kitchen. You might have [installed] central air conditioning….Many people have done a lot of work without permits in the past, and there are potential safety situations in the village.”

Sobel summed up the new law as “compliance instead of enforcement.”

The Butterfly Effect

Robert Sedaghatpour of Great Neck gave a presentation on the Monarch Butterfly Initiative, whose aim is to bring back that migrating species to the numbers of decades past. By some counts, its population has dropped by 90 percent during the past 20 years.

Sedaghatpour asked the village to pledge itself to doing such simple things as leaving aside small public spaces to plant nectar-bearing flora, leaving certain grasses unmowed, so the monarchs can feed on what might look like an ugly weed.

Under the leadership of the National Wildlife Federation (NWF), villages can take what is called the Mayor’s Monarch Pledge and also create at least one NWF-certified wildlife habitat.

Sedaghatpour informed the board that the monarch is the “poster child” for environmental deprivation, and asked the village to undertake at least three of the 25 items the NWF has determined will make a community environmentally friendly.

“I’m confident there are three things on the list we can do,” affirmed Village Attorney Peter Bee.