“I congratulate you at the beginning of a great career,” so wrote Ralph Waldo Emerson to the young Walt Whitman in 1855. Emerson, the self-styled philosopher king of American letters, had read Leaves Of Grass, Whitman’s lifelong work-in-progress and was mightily impressed. He was determined to track down the young poet and give him his blessing.

For Whitman, the letter—and the reception to his collection—was vindication of a long apprenticeship. Emerson and his fellow New England transcendentalists had long dominated American letters. Now this brash upstart from Long Island was set to make his mark. A prolific author and poet, Whitman was an American romantic to rival the greats of English literature—Wordsworth, Keats, Lord Byron, Coleridge and Shelley. Whitman came from a family that was old New York stock—English father, Dutch mother. In their prime, the Whitmans owned 500 acres of land on Long Island, before suffering through a harsh British occupation during the Revolutionary War. Walter Whitman moved the family to Brooklyn in search of carpenter’s work. His dreamy son sought out the cultural amenities the city had to offer, settling on a career as a newspaper man at various Brooklyn publications, before finding a teaching job back on Long Island. All the while, he kept writing. In Whitman’s day, newspapers sprinkled their pages with verse, some of it hokum, but some of it cutting-edge.

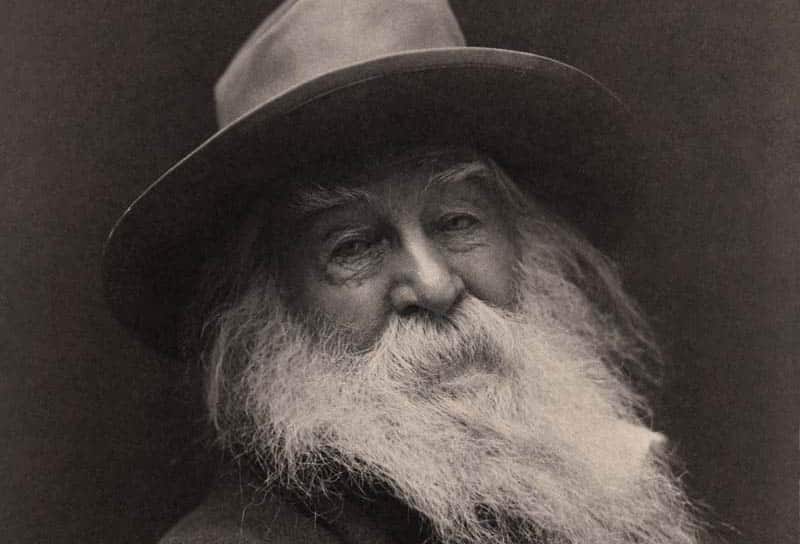

For Whitman, Long Island was the homestead, but New York City was the world. Whitman knew the score about his homeland. America was great material for the poet, but it was also philistine to the core. Poetry might be something a young man wrote on the sly, he may even publish verse in those same newspapers. But nobody becomes a poet. Whitman was good at self-promotion: the flowing white beard, the vagabond poet of the people. Once he was recognized by Emerson, he was welcomed into the literary salons of Boston. Whitman had his subject: This young, brash, self-confident nation. Right off the bat, Whitman announced his intentions in the opening lines of his magnum opus.

For Whitman, Long Island was the homestead, but New York City was the world. Whitman knew the score about his homeland. America was great material for the poet, but it was also philistine to the core. Poetry might be something a young man wrote on the sly, he may even publish verse in those same newspapers. But nobody becomes a poet. Whitman was good at self-promotion: the flowing white beard, the vagabond poet of the people. Once he was recognized by Emerson, he was welcomed into the literary salons of Boston. Whitman had his subject: This young, brash, self-confident nation. Right off the bat, Whitman announced his intentions in the opening lines of his magnum opus.

I celebrate myself and sing myself,

And what I assume you shall assume,

For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you.

Whitman was not the prototypical man of letters who sequestered himself in a small room, shielded from a harsh world. The man, instead, jumped headfirst into American life. Diversity had a different concept in Whitman’s day. It meant celebrating the nation’s different regions, its crops, its peoples, manners, morals and codes of conduct. Whitman was the first poet to embrace all of America. It also made for much exuberant verse.

One of the Nations of many nations, the smallest the same and the largest the same,

A Southerner soon as a Northerner, a planter nonchalant and hospitable down by the Oconee I live,

A Yankee bound my own way ready for trade, my joints the limbered joints on earth and the sternest joints on earth,

A Kentuckian walking the vale of the Elkhorn in my deer-skin leggings, a Louisianan or Georgian,

A boatman over the lakes or bays or along coasts, a Hoosier, Badger, Buckeye

Did he get carried away? At times, yes. The subject, even in the more innocent days of the mid-1850s, was probably more than the poet could manage. Still, Whitman significantly expanded the frontiers of American letters. Think of the big, sprawling epics that would follow: The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Moby Dick, Of Time And The River, USA: The 42nd Parallel, 1919, The Big Money, The Adventures of Augie March and On The Road. Whitman was there first. Tom Wolfe, for one, tried to goad his fellow writers by referring to the United States as a big beast crying “Feed me! Feed me!” a sentiment that Whitman would approve of.

During the Civil War, Whitman was employed by the government in the Department of the Interior. He attended to the wounded and wrote many letters to the families of those same soldiers, an act of generosity that earned him many lifelong friends. Whitman was deeply affected by the war and its aftermaths. The nation was losing its old innocence, now descending into an era of greed and sloth. A concerned Whitman addressed the situation in prose, penning the well-read Democratic Vistas. The poet aimed to get to the heart of the matter. He called for restoration in both the life of the individual and that of the commonwealth. “Household to nation” could have been the man’s message. The sacrament of marriage and parenthood was a starting point: “Will the time hasten when fatherhood and motherhood shall become a science—and the noblest science?” From there, it was participation in the life of the community. Whitman envisioned a “pleasant western settlement or town,” where the locals come together to attend to “farming, building, trade, courts, mails, schools, elections” all in a fruitful manner.

Yes, the man was optimistic about the American prospect. Whitman’s America was both a city nation and a frontier nation. Democratic living did not necessarily mean the franchise, it meant men and women staking out the land, building homes and communities.

Philistine America caught up with Whitman. He was famous, but hardly well-off enough to write full time. He eventually retired from government service, living quietly with his brother and sister-in-law and their children in Camden, NJ. He died on March 26, 1892, a beloved poet to his many readers.

The coming years were bound to see a backlash to Whitman’s romanticism. As the decadent 1890s yielded to the early 20th century, the verse of T.S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, Robert Frost and Wallace Stevens took a more jaundiced look at modernity and its effects on the human spirit. Whitman isn’t going anywhere. His books are in print. Long Island—and the rest of America—has schools, poetry contests and awards in his name. He was a man with a large heart and an expansive mind. Sin of a wasted life? Never in the case of Walt Whitman.