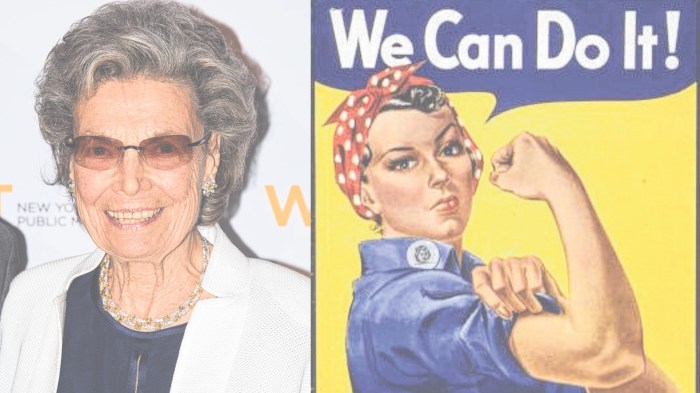

As many continue to celebrate Veteran’s Day this week, residents of The Sinclair in Port Washington are celebrating the life of Murray Kaner, a 98-year-old World War II infantry platoon sergeant whose story spans the Pacific battlefield and decades of civic and professional achievement.

Kaner, originally from Borough Park, Brooklyn, enlisted in the Army at 17, just out of high school at New Utrecht, driven by patriotism and a desire to serve.

“My mother had to sign the papers for me to go in,” he recalled. Initially, he hoped to join the Air Corps, but he was rejected for flat feet. “I said, ‘I’m going to end up sitting in an airplane,’” he said, laughing. Instead, he entered the Army Specialized Training Program and attended Norwich University in Vermont before being called to active duty. “They needed men,” he said, explaining that the Army overlooked his age to fill its ranks. He knew he had a better chance at a better assignment if he had volunteered instead of waiting to be drafted.

Kaner’s military journey began with 17 weeks of basic training, followed by a short furlough home and then transit from Fort Dix to Camp Kilmer. From there, he boarded a liberty ship bound for the Pacific.

“We went through the Panama Canal into the Pacific and ended up in Hawaii,” he said. After advanced infantry training in Hawaii, Kaner was sent to the 33rd Division in the Philippines, where the Battle of Baguio awaited.

“Baguio was in the mountains in the Philippines, where Luzon is,” he said. “My introduction to battle was house-to-house patrol; if we got gunfire from the buildings, we brought the tanks in and blew the building down.” Kaner and his fellow soldiers navigated dense, tropical terrain, often under heavy Japanese fire. “There was a lot of walking,” he said. “The jungle was very dense. We had to be very careful; there were poisonous snakes everywhere. We used machetes to cut through the grass.”

The Battle of Baguio, part of the larger Luzon campaign, was critical for American forces seeking to liberate northern Philippines from Japanese occupation. Baguio, then a hill station and summer retreat for wealthy Filipinos and Japanese administrators, presented unique challenges: steep terrain, fortified enemy positions and civilians trapped in urban areas.

Kaner, a young recruit from Borough Park, learned quickly under the tutelage of seasoned veterans.

“We went into fighting right away. There was no learning curve,” he said. “I had to learn quickly.” He credited the experience with teaching resilience, teamwork and leadership.

“I learned to pay attention to other people’s problems. You never leave anybody behind,” he said. His unit consisted mostly of men from the South and Kaner was promoted to squad leader due to his prior military training. “I had 12 guys with me. We were all from different backgrounds, but we worked together.”

During his six months in the Philippines, Kaner endured tropical heat, monsoon rains and relentless combat.

“I got there in February and stayed until the end of the war in August,” he said. “There’s no fall there. It was summer, hot and humid. But in the mountains, it was cool.” Kaner remembered the Filipino people and guerrillas who fought alongside American forces. “They fought alongside us. They were a great help,” he said. English was widely spoken, easing communication, but the daily realities of war — hunger, exhaustion and constant danger — were ever-present.

After the Philippines, Kaner’s division was sent to Panama to train recruits in jungle warfare.

“It was hot and humid, again nothing like New York. We had to patrol carefully, everything buttoned up,” he said. He recalled the rigorous training, cutting through dense foliage and avoiding venomous snakes, preparing soldiers for future combat. “We were teaching jungle fighting to new guys,” he said.

Returning home, Kaner took advantage of the G.I. Bill, attending Brooklyn College and later Queens College while working nights.

“All I knew at that point in my life was combat and war, how to kill. Everything else after that was babyish; it was difficult for me to sit in a college classroom immediately back from the war,” he said. His post-military career spanned more than 40 years with the International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union, where he eventually became business manager of the trucking division, representing warehouse and transportation workers across New York.

In 1949, Kaner married his girlfriend, Shirley, whom he met on a blind date before leaving for the war. The couple raised two sons and moved from Brooklyn to Great Neck in 1991.

“We needed room. We had a three-room apartment in Brooklyn, so we moved out to the country,” he said. After decades in Great Neck, Kaner relocated to The Sinclair in Port Washington in 2021.

Nearly a centenarian, Kaner maintains a disciplined lifestyle. He reads the newspaper front to back every morning, stays active with daily physical therapy and enjoys simple pleasures, including Chinese food and pepperoni pizza.

“I read the newspaper front to back every morning,” he said. “I stay active and I like to keep my mind sharp.”

Kaner remembers small details of wartime life vividly, from combat equipment to meals.

“We carried an eight-pound M1 rifle,” he said. “The K rations were waterproof wax boxes with pork and beans and two cigarettes. I never smoked, so I traded them for chocolate bars.” He also recalls moments of camaraderie among soldiers. “We were in it together. Everybody was from all over the country, all financial backgrounds and religions. That’s what got us through.”

Despite decades of civilian life, Kaner’s military experience shaped his approach to work and family.

“I got along well with my squad; I wasn’t crazy with power,” he said. Lessons learned on the battlefield helped him navigate union leadership and advocate for workers.

Kaner says his sons also remember his military discipline in everyday life.

“I used to say ‘off and on’ when it was time to do something, short for ‘off your ass, on your feet,’” he said with a chuckle.

Reflecting on his life, Kaner remains humble and focused on resilience.

“I still feel that way,” he said of coming back from combat. His story, from Brooklyn to Baguio, Panama and back to New York, offers a rare, first-hand perspective on the experiences of the generation that fought World War II and quietly rebuilt America. At The Sinclair, Kaner continues to inspire residents and visitors alike with his courage, discipline and unwavering dedication.