After about five frustrated days of jury deliberations, Judge Mark Cohen was preparing to declare a mistrial in the cover-up case against an ex-Nassau County police brass member when a court officer handed him a note: The jurors had reached a verdict.

With the clock running out, two jurors and Cohen—a Suffolk judge brought in after two Nassau judges had recused themselves last year—were about to go on vacation, threatening to nullify the month-long trial. Shortly before 8 p.m. a hush fell over the small crowd at Nassau court in Mineola on Feb. 15 as the jury foreman read the verdict. William Flanagan, the retired second deputy Nassau police commissioner, readily looked on.

He was found guilty of conspiracy, a misdemeanor, and not guilty of receiving reward for official misconduct, a felony, after being convicted of two misdemeanor official misconduct counts on Valentine’s Day.

“This isn’t over,” Flanagan calmly told reporters outside the courtroom.

It was his first public statement since he’d given a round of interviews following his March 2012 arrest—prosecutors had unsuccessfully tried to use those quotes as evidence since he never took the stand.

“We’re very disappointed that the jury mistakenly convicted him of the misdemeanor,” said Bruce Barket, Flanagan’s Garden City-based attorney, who vowed to appeal. “They exonerated him of the most serious charge. The appellate court will take care of the rest.”

District Attorney Kathleen Rice, the top-elected Democrat seeking re-election in Republican-controlled Nassau, now faces strained relations with the police agency her prosecutors work closest with after she took down its disgraced ex-third top cop, sources in both departments say. As two of Flanagan’s alleged co-conspirators await trial—the highest-ranking of the brass to do so after an especially scandalous year for Nassau cops—Rice echoed a Press expose that had sparked Flanagan’s arrest and conviction.

“This case has always been about making sure that there isn’t one set of rules for the wealthy and connected, and another set for everyone else,” Rice said in a statement. “The jury validated our belief in that important principle.”

The scandal erupted five months after Bronx prosecutors accused 15 NYPD officers of fixing tickets in what some described as New York City’s biggest police favoritism case in a half-century. Those cops pleaded not guilty and are awaiting trial.

As far as Long Island law enforcement cover-up scandals go, Flanagan’s conviction may be the most serious case since a New York State commission investigated widespread allegations of Suffolk County police corruption in the 1980s—assuming that discrepancies revealed at the now-shuttered Nassau police crime lab were just mistakes and not acts intended to sway cases.

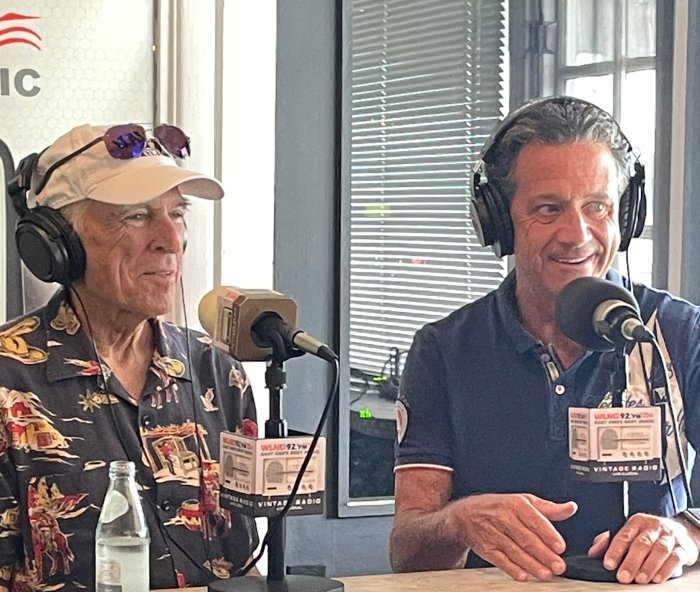

Gary Parker, a CPA from Merrick who asked his police friends’ for help quashing the arrest of his son, Zachary, was a star witness at Flanagan’s trial (Photo by Rashed Mian/Long Island Press)

Nassau jurors unanimously agreed that Flanagan had joined a conspiracy to return electronics stolen from John F. Kennedy High School in Bellmore in May 2009 by then-17-year-old student Zachary Parker as a favor to Parker’s father, Gary, a donor to a nonprofit Nassau police foundation, who wanted to avoid Zach’s arrest. But, by acquitting Flanagan of taking three $100 Morton’s steakhouse gift cards from the Parkers as a reward for misconduct, jurors had doubted that there was a quid pro quo, apparently buying the defense argument that the two were friends who’d exchanged gifts before.

“We realized that it was a conspiracy from day one,” one juror told the Press the night of the verdict. “They did what they did. They can’t undo that.”

Now that the first of the conspiracy cases have wrapped, one nagging question persists: Why should a jaded public care?

CALLING SERPICO

For a case that required jurors to listen to 18 witnesses, hear dozens of emails read aloud and watch what observers estimated was a record number of sidebars over 12 days of testimony, there was at least some star appeal to spice things up.

Those who sat with Flanagan supporters were high-ranking current and former officials, including his old boss, retired Nassau Police Commissioner Lawrence Mulvey, and Rep. Peter King (R-Seaford), who told the Press: “Bill’s a good friend.” Gary Parker testified that Bill O’Reilly of Fox News Channel billed the Nassau County Police Foundation—a group fundraising for a new police academy the two donated to—for $600 worth of his Pinheads and Patriots books. Parker also testified he’d asked for Flanagan’s help while the ex-cop was securing the 2009 U.S. Golf Open at Bethpage State Park.

But, beyond the splashy celebrity lure, such cases can have a real chilling effect.

“There’s an old saying: Everybody does it,” says Peter Cardalena, a St. John’s University criminal justice professor, Floral Park-based attorney and retired NYPD officer. “We just let it roll off our backs. The public should be concerned.”

He recalls students telling him when they think they’ve been improperly stopped by police but rarely report the allegations to internal affairs investigators because they feel “nothing can be done.” Cardalena counters that police retraining is routinely ordered after misconduct claims are made—a sign such allegations are taken seriously.

Police Commissioner Thomas Dale—whose first task was closing half of eight precincts—was hired halfway through a 20-month period in which four cops died in the line of duty and oversaw a year in which a half dozen police employees were arrested. Last May he had the Nassau County Legislature grant him the power to fire officers as he sees fit without arbitration, although the Nassau County Police Benevolent Association is fighting that move in court.

Still, by all accounts, 2012 was the department’s worst year in recent memory. Aside from Flanagan’s two alleged co-conspirators—former Deputy Chief of Patrol John Hunter and retired Det. Sgt. Alan Sharpe—ex-Nassau Police Officer Michael Tedesco pleaded not guilty in December to 109 charges alleging he spent shifts at his mistress’ house, police aide Frances Colvin pleaded not guilty to harassing a romantic rival, and another cop was sentenced in June to community service after admitting to shoplifting $40 of baby food. Inspector Thomas DePaola was also demoted for downgrading crime statistics in July.

Justin Hopson, a former New Jersey State Trooper who blew the whistle on corrupt cops and is the author of Breaking the Blue Wall: One Man’s War Against Police Corruption, says Dale will have to do more than fire bad apples to restore public trust in the department.

“Every act of police corruption needs to be unearthed, investigated properly and prosecuted,” he tells the Press, adding that Dale needs to “create a cultural sea change, one where the police police one another.”

Inspector Kenneth Lack, the department’s chief spokesman, declined to comment for this story. Rice’s office referred questions back to her statement.

OFFICE POLITICS

The difference in opinion between police and prosecutors over whether Flanagan should have ever been charged could be measured in the distance separating his supporters and the district attorney staffers seated on opposite sides of the courtroom during the trial.

How much that rift carries over into everyday inter-agency cooperation—or lack thereof—is open to debate, although observers agree that the internal politics is more an issue than the case’s potential impact when Rice’s re-election campaign ramps up later this year.

“My gut says the verdict has its own implications but it’s going to be like a tree falling in the forest—it’s not going to have any political implications,” says Jerry Kremer, a former state Assemblyman turned LI Democratic strategist.

Although representatives for the police and the prosecution declined to discuss the rift on the record, those close to the situation agree that there are fences in need of mending.

“I think there’s relationships that should be developed and made stronger…for the continued success of policing and prosecuting in Nassau County,” says James Carver, president of the Nassau PBA, which has supported Rice’s past campaigns.

Nassau County Attorney John Ciampoli is confident that both sides will eventually bury the handcuffs.

“This is not the first person in a police force who’s been charged with a crime,” says Ciampoli. “This comes up in the course of business. It’s come up before; it’ll come up again. The professionals on both ends are working through it.”

In her statement the night of the verdict, Rice acknowledged that the case is a black eye for the beleaguered police department.

“This is a huge win for the public, but it’s also a sad day for an awful lot of incredibly hard-working Nassau cops who do their brave jobs honestly every day,” Rice’s statement reads. “This case is a reminder that to safeguard the public’s trust and the integrity of our honest officers, we must be vigilant in our fight against corruption and misconduct.”

Still, don’t expect the issue to spark any action in the halls of county government.

A spokesman for Presiding Officer Norma Gonsalves (R-East Meadow) says there are no proposals or public hearings in the county legislature stemming from the case. A spokeswoman for County Executive Ed Mangano did not respond to a request for comment.

JAIL CELL DOORS

Flanagan, who resigned following a year in which he was ranked LI’s highest-paid cop, is scheduled to be sentenced May 1. Misdemeanor convictions are punishable by up to a year in jail, although it’s doubtful he’ll serve much time—if any.

His co-defendants, Hunter and Sharpe, had their cases severed from Flanagan’s and they are due back in court March 15. Their attorneys declined to comment.

Zachary Parker, the burglar who was never arrested by police, pleaded guilty to charges in a grand jury indictment after prosecutors investigated the cover-up allegations in the Press. He’s serving up to three years in prison.

How many others like him whose cover-ups were never exposed we may never know.