Several Long Island communities have long feared that their property taxes will rise starkly when the power plants in their districts are either shut down or reassessed at a lower value due to their declining efficiency. As recent developments in Nassau and Suffolk have shown, that day of reckoning may have finally come.

The details vary depending on the power plants’ locations, but the dynamic is the same. Long Islanders pay some of the highest utility bills in the nation as well as some of the highest property taxes in the region. The effort to reduce one cost seems to come at the expense of the other.

But Long Island’s utilities have grown tired of footing the bill so public officials, from school superintendents to village mayors to county leaders, have to make some very tough decisions.

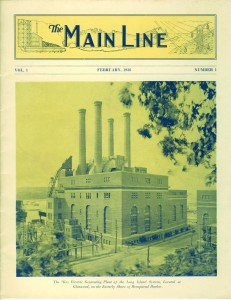

Now that National Grid has begun to demolish its nearly century-old Glenwood Landing power plant, which hasn’t generated a significant amount of electricity in decades, Sea Cliff Mayor Bruce Kennedy has had to assure homeowners in his village that their school taxes will not suddenly rise 25 percent next year—as some have feared.

“We are going to see increases,” he tells the Press, “but they’re going to be spread over a 15- to 30-year period so it’s going to be completely manageable.”

The utility paid $21.4 million in taxes in 2011-2012, $22.6 million in the 2012-2013, and $23.6 million in 2013. Last January, the property’s assessed value was cut in half, according to National Grid, which reduced its tax burden $11 million.

In 1999, tax revenue from the old plant contributed about 30 percent of the North Shore Central School District’s $45 million budget; now, according to Superintendent Ed Melnick, it’s 20 percent of the district’s nearly $94 million budget.

“We do not yet know what percentage that would be lowered by for next year but the maximum we anticipate would be 10 percent,” Melnick tells the Press in an email.

State Sen. Carl Marcellino (R-Syosset) and Assemb. Charles Lavine (D-Glen Cove) were able to get an additional $2.5 million in the state budget to soften the blow to the North Shore district, but it’s a one-shot deal.

“The homeowner shouldn’t see that much [increase],” the state senator says. But “there’s no doubt that the citizenry, the homeowner, will see an increase in their taxes.”

Watching this process unfold has been taxing indeed.

“Everybody has been wringing their hands—just wringing their hands—for 30 years!” exclaims Karin Barnaby, a longtime Sea Cliff resident, who has been circulating a petition to save the Glenwood Landing power plant from pending demolition, slated to be completed by December.

“I’ve always said to everybody, ‘Look, this is a fool’s errand,’” Barnaby tells the Press. “I have no illusions about the futility of this project in the face of National Grid’s power and influence, but it has to be said, anyway.”

Barnaby would like to see Glenwood Landing resemble a place like the Chelsea Piers Connecticut sports complex, which opened across the Sound in Stamford in 2012, transforming Clairol’s former warehouse into skating rinks and other recreational outlets.

“All I’m asking is for time so the notion can be explored,” she says. “It’s a fabulous building.”

Barnaby recently presented almost a 1,000 signatures on her petition to Judi Bosworth, the supervisor of the Town of North Hempstead, who said through a spokesman that she “will look at all opportunities for waterfront revitalization.”

Assemb. Lavine supports Barnaby’s “quite creative” idea to repurpose the old brick facility.

“For many, many years it’s been no secret that the North Shore School District has benefitted from the placement of that plant within the confines of its geographical district,” says Lavine. “And for many years we’ve known that that day was going to come to an end.”

But he says it’s too soon to predict what the final tax bite will be until the county’s re-assessment is completed “after the demolition occurs—if it occurs.”

And he hopes it won’t.

“I’ve been in the building,” Lavine says. “It is a piece of architecture the likes of which we unfortunately won’t see again….It would be really, really great for the community if we could figure out some way to keep that structure and make it productive.”

Sen. Marcellino views the Glenwood property differently.

“That building is full of asbestos,” he says, adding that to make the waterfront viable “would require major dredging… The silt is backed up right to the bulkhead; you can’t even bring a barge in there.”

Cursing the Darkness

“It’s very unfortunate how the community chose to handle this issue,” says former LIPA trustee Neal Lewis. “They got a good tax return for many, many years, but rather than plan for the change that was coming, they’ve been in denial, seeking elected officials to keep the LIPA contract going for an old plant that LIPA had no need for. They should have set up a process years ago so maybe by now they’d have the zoning in place and have found community agreement on potential uses [for the site].”

Until January, Lewis had served four years on the board of LIPA trustees, an unpaid position. He said that the board commissioned an outside auditor to assess the taxes that LIPA was paying for its big power plants in Glenwood, Northport and Port Jefferson. The 2010 report “said that we were as much as 90-percent overtaxed at these various plants. Then I had to say, ‘What is my duty as a fiduciary? I’m on the board acting in trust for the people of Long Island…If we’re overpaying in taxes what the current law would require, then you have to challenge it.’”

And so began the tax certiorari cases—the property tax challenges—that are giving Long Island’s body politic so much agita today.

LIPA wants to reduce the assessment of the Northport power plant by 80 to 90 percent, which could raise taxes in the Northport-East Northport school district by 60 percent, according to the town. Last summer a proposal had been worked out in Albany with LIPA and the state Legislature at the behest of Gov. Andrew Cuomo that would have softened the blow locally by spreading the increase in 10-percent increments over many years but the town and the school district balked.

Huntington Town Councilman Mark Cuthbertson is rather blunt when he assesses what that deal could mean for the district and the town.

“Accepting that agreement is basically accepting the bankruptcy of the Northport-East Northport school district,” says Cuthbertson. “Our position is that we would be better off and would get a better result by going to court than accepting their offer.”

They’ve retained Lou Lewis, an attorney at Lewis & Greer, a Poughkeepsie law firm, who had represented the Shoreham-Wading River school district during the controversial closure of the Shoreham nuclear power plant—a long, drawn-out process.

“Everyone was very concerned [at the time] but you know the school district is still there, and they’re getting more state aid now,” the he tells the Press. “A lot of state aid is based on formulas that take income from taxes into consideration; if those taxes go down, then your state aid will go up.”

Now the Northport tax certiorari case is in the pre-trial phase, the attorney says, while he tries to get LIPA and National Grid to supply information his appraiser needs to counter their claim. It’s been “like pulling teeth,” Lewis says.

Known for its iconic four red-and-white striped smoke stacks, the Northport plant produces 40 percent of Long Island’s electricity but it is also more than 40 years old, according to Sen. Marcellino, whose district also stretches into Huntington Town.

“They’re looking to cut their losses,” says Marcellino, explaining the motives of the utility, PSEG Long Island, which is being represented by LIPA in the court case. Marcellino said that he and Sen. John Flanagan (R-Smithtown) thought that the town and the school district should have accepted the governor’s compromise with LIPA because that would have eliminated about $200 million in back taxes, while implementing future tax increases “over a 10-year slide,” as he put it, to cover the “50-percent drop” in the power plant’s assessed value.

“If you can wipe out $200 million of potential debt, I think that’s pretty good,” Marcellino tells the Press.

But Huntington and the Northport-East Northport school district have said the increases are too onerous and they dispute the drastic reduction in the plant’s assessment.

“I’m not happy with the proposal that New York made for settling these things,” says Lewis, the town’s attorney. “I think it was based on a misunderstanding of where the data was coming from.”

He says the Northport power plant’s reduced value was determined by LIPA, which “is the main party of interest in these lawsuits because…they’re going to be paying the taxes on the property!”

Basically, Lewis explains, the utilities are “under pressure to reduce their costs to their customers, and one way they feel they can do that is pay less in taxes…. But it’s very deceptive because their customers are the same people who are also the taxpayers… You’re taking money out of one pocket and putting it in another.”

“Power plants pay a significant portion of school taxes in the communities they are located in,” observes Matt Cordaro, a former utility CEO who is now a LIPA trustee but was not speaking as a representative for the board. He remembers working for the Long Island Lighting Co., LIPA’s precursor, when it was trying to get a tax reduction for the Glenwood Landing plant in the 1980s.

“We took out two units [from the original brick building] and they wouldn’t reduce our taxes,” he says. “The only time we got a concession we actually had to clip the wires that were there and demonstrate that it wasn’t a power plant.”

On the other hand, Cordaro fondly recalls, “The brickwork is just tremendous.”