Less than half of the 23 bills that a New York State heroin task force proposed two weeks ago passed the state legislature before lawmakers went on summer break last week.

The 11 bills that passed in a much-anticipated legislative package deal mostly deal with treatment and prevention of heroin and prescription painkiller abuse, while only some bills that would have enacted harsher penalties in drug crimes made the cut.

“Government doesn’t really solve problems like this,” said Gov. Andrew Cuomo, who signed the bills into law Monday. “These problems get solved when everybody takes responsibility towards the issue.”

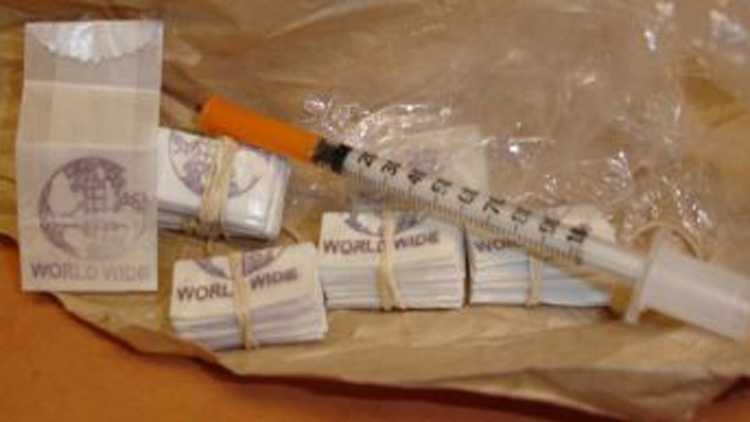

The legislation aimed at combating the statewide heroin epidemic that has gripped Long Island for years followed the task force’s 18 public hearings in nine weeks this spring, busloads of anti-drug advocates lobbying Albany and a steady stream of major drug busts in the state—home to a third of the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration’s heroin seizures nationwide last year.

Read More: How Long Island is Losing its War on Heroin

Among the most notable new laws requires insurers to cover substance-abuse treatment based on decisions made by medical professionals and requires insurance companies use the same criteria as rehabilitation providers.

“We made a lot of comments on the language of the bill and we brought families up to Albany to advocate for this,” said Jeffrey Reynolds, executive director of the Long Island Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence. “We’re trying to curb what we’ve seen, which is insurers trying to create barriers to treatment.”

Other new laws were also aimed at increasing the availability of rehab. One directed the state Office of Alcoholism and Substance Abuse Services (OASAS) to create a relapse prevention program to provide case management and referral services for people who successfully complete treatment. The state health department will also develop a new model of services for those in recovery with the goal of reducing reliance on emergency room services.

Another law will allow parents to have drug-abusing children assessed by an OASAS-certified provider through the Person in Need of Supervision (PINS) program. A similar task force proposal that was not included in the final package would have also allowed courts to require a PINS child to undergo treatment. The measure is aimed at helping abusers who are over the age of 18 who refuse parents’ attempts to get them treatment.

Other failed bills would have directed OASAS and the Department of Corrections and Community Supervision to look into converting closed correctional facilities into rehab facilities.

Among those that passed were new laws expanding the use of naloxone, an opioid-overdose antidote known by its brand name, Narcan, which has been credited with saving countless people from fatally overdosing.

One of the new laws require naloxone kits to include instructions on how to administer the drug, how to identify an overdose and where to find treatment services. Another allows health care professionals and pharmacists greater flexibility in prescribing Narcan, ensuring it’s more readily available. On the other hand, a bill that would have allowed schools administer naloxone was not signed into law.

Other new laws add drug prevention information to junior and high school health class curricula and a public awareness program by the OASAS and the state health department.

Among the rejected bills was one that would have put guidelines for prescription drug take-back events on the OASAS website and another that would have created standards for a continuing medical education program for drug prescribers. Another bill that didn’t pass would have limited prescriptions of controlled substances to patients suffering from acute pain.

“We in the Senate agreed that that prevention and treatment was most important,” said state Sen. Phil Boyle (R-Bay Shore), the chairman of the Senate’s heroin task force. “But we realize that there need to be criminal penalties.”

Most of the bills that were cut from the deal between Cuomo and the Senate were designed to tighten up law enforcement of drug-related crimes, although some still made it through.

The failed bills would have classified the transportation or sale of an opioid that causes a death as homicide, the theft of a blank prescription form as grand larceny and the sale of a controlled substance within 1,000 feet of a drug treatment center as a B felony.

One bill that was sponsored by Boyle would have made harsher penalties for transporting an opioid more than five miles within New York or between counties. Boyle said that he was disappointed that the bill failed.

“Opioid drug dealers come out of New York City, Long Island and all over upstate,” he said. “You can get heroin bags pretty cheap in the city but once you get up to Plattsburgh, you can sell them for six times as much as in the city. I would have liked to have seen the bill get passed.”

Another rejected bill from the task force’s original recommendations, dubbed the Criminal Street Gang Enforcement and Prevention Act, would have increased penalties for gang-related drug crimes. Other rejected bills would have restricted drug dealers for participating in the SHOCK incarceration program—rehabilitative prison boot camp for young offenders—to receive drug abuse treatment and required treatment facilities to notify local police of convicts being treated in court-mandated programs.

These bills were replaced by a new set that authorize investigators from the health department’s Bureau of Narcotic Enforcement (BNE) to access criminal histories of doctor-shopping suspects. Another increases the penalty for obtaining controlled substances by impersonating as a doctor or pharmacist or forging a prescription.

Other law enforcement measures that passed increased penalties for a doctor or pharmacist to uses his or her job to illegally sell prescriptions. Investigators were also granted more tools in probing allegedly unscrupulous doctors and pharmacists.

All of the measures came after the governor announced a plan to add 100 New York State Police investigators to its narcotics unit and train college staffers how to identify signs of addiction. Before the bills were signed into law during an event at Binghamton University, one upstate lawmaker noted that prevention is paramount, if the need for treatment and enforcement is to be curbed.

“All important is the public education campaign,” said Assemb. Donna Lupardo (D-Broome County), a co-sponsor of several of the laws. “Honestly, it’s hard for us to wrap our heads around the attraction to this drug.”