Armed with colorful signs preaching peace and love, interfaith groups mingled with local Muslims in a parking lot adjacent to Rep. Peter King’s (R-Seaford) Massapequa Park office four years ago last month to condemn the hearings the congressman was planning to hold on “radicalization” of Muslim Americans.

The “pray-in” attracted a diverse group of Long Islanders who were worried that the hearings in Washington, D.C., which had the potential of attracting a global audience, would further stigmatize Muslim Americans by casting a whole religious community under a dark cloud of suspicion.

Several demonstrators were so incensed that they not-so-subtly accused the congressman of embarking on a personal crusade that mirrored notorious US Sen. Joseph McCarthy’s scorched-earth pursuit of alleged Communists inside the United States amid pervasive Cold War paranoia.

Holding various pro-Muslim signs, demonstrators channeled their inner-George Washington, unfurling a banner that blared in giant, bold letters: “To Bigotry, No Sanction; To Persecution, No Assistance.”

King, who in various interviews at the time scoffed at the notion that he was negatively stereotyping all Muslims, was hardly alone in wanting to explore the so-called “radicalization” of Muslim Americans.

King’s supporters defended his actions during the protest outside his office, and they also came out in full force a few weeks later in New York City. Standing on the corner of 38th and Seventh Avenue on a cold, dreary Saturday afternoon, they also protested the so-called “Ground Zero Mosque”—a proposed Islamic Center intended to inspire interfaith dialogue but criticized as insensitive to victims of the Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attacks.

“Never Forget 9/11: No Jihad Mosque,” read one sign that day.

“No Sharia Law in the USA!” declared another.

At the same time, a counter demonstration was heating up a few city blocks away. Hundreds of Muslim Americans joined interfaith groups in the pelting rain to reject the misguided notion that their religion is somehow responsible for the murderous misdeeds of fanatics, who, they say, have co-opted a perverted version of Islam to justify suicide bombings, attacks on civilians and all-around bloodlust.

While the protests generated a deluge of news coverage—and, lest we forget, incessant banter from talking heads on cable television—they did little to convince King to abandon his plans.

Four days after the NYC protests, on March 10, 2011, King, then the chairman of the House Committee on Homeland Security, held his first in a series of five hearings in Washington, D.C. The hearing drew such a large contingent of media members that dozens of reporters were forced into a stuffy overflow room replete with spotty Wi-Fi and an old TV perched atop a rolling stand from where the proceedings were streamed live.

In his opening remarks, King reaffirmed his commitment to exploring radicalization of Muslims in the US and—not surprisingly—expressed shock at the rhetoric the hearings provoked.

“To back down would be a craven surrender to political correctness and an abdication of what I believe to be the main responsibility of this committee—to protect America from a terrorist attack,” King told the packed audience.

Not only did the hearing ignite a tidal wave of controversy, but it also gave Americans an intimate glance of King: an outspoken and unapologetic congressman from the South Shore and a leading national security hawk.

King would not be the only political figure to hold a public discussion on radical extremism. Almost exactly four years after King’s initial hearing, President Obama last month waded into the delicate waters of discussing Islamic terrorism, albeit without ever linking the two terms, holding what he called a “Countering Violent Extremism” (CVE) summit–and resurrecting yet again intensely passionate, polarizing views from both sides of the issue, drawing consternation from the right while also opening himself up to critics concerned about the effect the discussion would have on everyday, peace-loving Muslim American families.

The firestorm that preceded King’s hearings did not materialize this time around; neither was there nationwide protests leading up to the summit. But the three-day White House event did spark backlash from several prominent human rights and Muslim advocacy groups worried that it would further stigmatize Muslim Americans by focusing solely on Islamic terrorists. Why not, some wondered, explore right-wing radicals and other homegrown extremist groups like the Sovereign Citizens movement?

The same groups also questioned the effectiveness and intent of the White House’s CVE strategy.

In an open letter to the Obama administration, a coalition of rights organizations raised longstanding concerns within the Muslim American community that the CVE—a practice in which law enforcement and community members essentially form a partnership to address perceived radical extremism in the community—could further erode trust, especially if law enforcement intends on gathering intelligence under the guise of community outreach.

That deep-seated distrust was born out of an aggressive campaign by local and federal law enforcement to covertly investigate potential extremism in the Muslim community in a post-9/11 milieu. Their gripes concerning potential intelligence gathering are not without precedent, say advocacy groups.

Since 9/11, Muslims have been the focus of NYPD spying—including on Long Island and Muslim Student Associations at local universities—and undercover operations by the FBI using informants to infiltrate mosques. (As the NYPD itself has admitted, the so-called Demographics Unit, which spied on Muslims in New Jersey, the five boroughs and Nassau and Suffolk counties, was unable to generate a single terrorism investigation despite months of undercover activity.) What’s more, the federal government, according to a lawsuit, went as far as placing men on the government’s secretive no-fly list and threatened to keep their names there if they refused to serve as civilian spies.

Meanwhile, the recent slaying of three Muslim American college students in North Carolina and the fatal shooting of an Iraqi man in Texas, who was snapping a photo of his first snowstorm, has Muslims on edge. The latter case has reportedly been ruled out as a hate crime.

This tension all comes as the Islamic State, also known as ISIS or ISIL, and other extremists groups in the Middle East and North Africa, continue to commit atrocities in the name of a bastardized version of a religion that the vast majority of Muslims don’t identify with, and actually call un-Islamic. Upwards of 60 countries are currently banding together to fight this new enemy, but there’s only so much this international coalition can do with bombs and brute force.

ISIS has proved adept at using the digital age to lure potential recruits through social media and spread anti-West propaganda. Its ability to poach new fighters from western countries is of particular concern to US authorities, according to Michael Steinbach, assistant director of the FBI’s counterterrorism division, who addressed a House Judiciary Committee in February.

The FBI estimates that up to 150 Americans have traveled or attempted to travel to Syria to join terror groups, he testified. Steinbach did not say how the agency arrived at that estimate.

“It is this blending of homegrown violent extremism with the foreign fighter ideology that is today’s latest adaptation of the threat,” Steinbach told the committee.

In response to global events and the concern that some Muslims in America could fall prey to ISIS’ propaganda, the White House held its extremism summit with leaders from several Muslim countries. While some Muslim advocacy groups acknowledge that the summit may very well have had the best intentions, they contend it still missed the mark.

“CVE’s stated goal is to ‘support and help empower American communities,’” a coalition of groups including the American Civil Liberties Union, Amnesty International, Council on American Relations [CAIR] and more than a dozen other groups, wrote in a letter, dated Dec. 18, 2014. “Yet CVE’s focus on American Muslim communities and communities presumed to be Muslim stigmatizes them as inherently suspect. It sets American Muslims apart from their neighbors and singles them out for monitoring based on faith, race and ethnicity.”

Essentially, the groups warned, as they did before King’s hearings, that the summit—and the CVE strategy—would once again alienate Muslims in America.

“They’re basing these programs on an absolute mythical junk-science premise, and that’s what Peter King’s hearings were based on,” Glenn Katon, legal director for Oakland, Calif.-based Muslim Advocates told the Press. “Like, ‘What are we going to do about ‘radicalization in the Muslim community’?’ That’s nonsense, there’s no such thing. Are there people in the Muslim community who have out-of-the-mainstream views? Yes. And there are among Jews and Christians and everyone else.”

“People’s political views,” he added, “even if they are extreme, have nothing to do with [whether] they [are] going to be the ones who commit violent acts.”

Cloud of Islamophobia

Muslim Americans for years have argued that they have been unfavorably targeted by law enforcement due to circumstances out of their control, thereby creating an atmosphere in which Muslims have bullseyes on their backs.

They point to assaults on Sikhs, who are oftentimes mistaken for being Muslim, the aforementioned slayings in North Carolina and Texas, and well-attended anti-Islam rallies in Europe, particularly in Germany.

And the wave of Islamophobia that has persisted, not only in the US, but also in other western countries since 9/11, is due in part to rhetoric from policymakers and hate groups, they argue.

But suspicion has also been cast in no small part due to attacks perpetrated by Muslim adherents—the Fort Hood shooting in 2009 that killed 13 people, Boston Marathon bombing in April 2013 that killed three and injured more than 200 spectators, and failed attacks either disrupted through sheer luck or work of law enforcement. And masked thugs uploading videos of brutal slayings on the Internet while saying they’re acting in the name of Islam does not help the cause for Muslims preaching peace and tolerance.

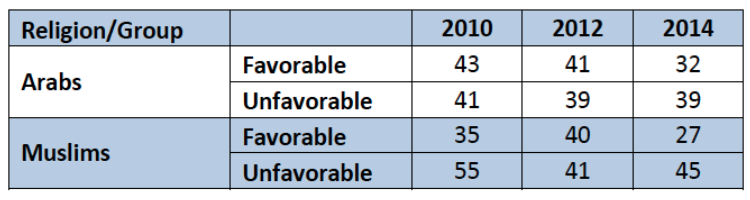

A poll conducted by the Arab American Institute in June 2014 perhaps best illustrates the deep divide between Arab and Muslims Americans and the rest of the country. The poll found that the favorability rating toward Arabs and Muslims in the US dropped precipitously between 2010 to 2014, from 43 to 32 percent and 35 to 27 percent, respectively. That earned Muslims the lowest favorability rating among all groups covered.

Another poll released a month later similarly captured unfavorable views toward Muslims. In its poll, the Pew Research Center found that Americans have more negative views toward Muslims than any other religious groups, including Atheists. (Jews and Christians received the highest overall ratings, 63 and 62, respectively, according to Pew.) The poll also discovered a partisan divide among respondents, with Democrats expressing significantly “warmer” feelings toward Muslims than Republicans (47 to 33).

Both polls were taken before ISIS began laying siege to large swaths of Iraq and Syria, targeting so-called apostates and enslaving women and children, and well before it began releasing horrifying Hollywood-style videos documenting decapitations of Americans and the caged immolation of a downed Jordanian pilot. The polls were also released prior to the massacre inside Charlie Hebdo, the satirical magazine based in Paris. It’s therefore difficult to discern whether Americans’ views have changed since the polls were first publicized.

But anti-Islam rallies sprouting up in Europe in reaction to these events do indicate, if not a rise in Islamophobia, at least a willingness to publicly denounce the religion that nearly a quarter of the world–some 1.6 billion people–worship daily.

What’s troubling Muslim advocacy groups is the way in which the US government is going about addressing extremism.

“Targeting any American on the basis of political activism or religious observance or extreme views—as opposed to unlawful action—violates our Constitution,” Hina Shamsi, director of the ACLU National Security Project, wrote in a blog post days before the CVE summit. “This is equally true when the government conducts the surveillance or when the government recruits community partners to monitor and report back to law enforcement. What results is a climate of fear and self-censorship, in which people must watch what they say and with whom they speak, lest they be reported for engaging in lawful behavior that the government vaguely defines as suspicious.”

Much has changed in the four years since King followed through on his plan to openly discuss Muslim “radicalization”: The Islamic State has emerged as a new threat, the US withdrew (sort of) from Iraq only to return again, Syria is crumbling amid a devastating humanitarian crisis, and the Middle East and North Africa, which saw the collapse of several regimes during the Arab Spring, is seemingly even more of a powder-keg than the years immediately following the Sept. 11 attacks.

Nearly 14 years later, Muslims are still at the center of it all.

Battle Within

When Obama appeared before a slew of world leaders and human rights organizations at the White House on Feb. 19 for the “Summit on Countering Violent Extremism,” he spoke in broad terms about what causes an individual to turn to a violent ideology: social strife, politics, sectarian conflict, propaganda, economic woes.

He spoke mostly about young people, who are perhaps more susceptible to online propaganda espoused by extremists than any other group of individuals.

“We have to address the political grievances that terrorists exploit,” Obama said. “Again, there is not a single perfect causal link, but the link is undeniable. When people are oppressed, and human rights are denied—particularly along sectarian lines or ethnic lines—when dissent is silenced, it feeds violent extremism.

“When peaceful, democratic change is impossible,” he added, “it feeds into the terrorist propaganda that violence is the only answer available.”

Obama was careful not to conflate Islam with extremism. He also spoke about the distorted impression of Islam in the news, the “lie” that the West is at war with Islam, and anti-Muslim sentiment in Europe.

King was not impressed.

“The way I looked at it from the outside, from what I heard, it was more like a touchy-feely type thing,” King told the Press about Obama’s hearings in a phone interview.

King, who was among the voices in Congress who criticized Obama for failing to label extremists Islamic, said he believes doing so would actually have been beneficial to the Muslim community because it would have distinguished them from extremists.

Asked if calling it an “Islamic Extremists Summit” would have provided ISIS with more ammunition to unleash as propaganda, King demurred.

“First of all those groups don’t need any excuse, they attacked us long before Guantanamo [Bay], long before any of the things they’re talking about now,” King said. “No, it’s almost as if we’re afraid, or the president is afraid, or the administration’s afraid, to identify this for what it is.”

Looking back on the five hearings he held over the course of 13 months, King remains adamant that it was the right step to take.

“I raised issues that had to be raised,” he said, adding that the same issues are relevant today.

“I think they were certainly on target…for instance the first hearing, which by the way people don’t realize I had three witnesses, two of them were Muslim Americans, the other was an African American whose son converted to Islam,” he said. “But the key Muslim American witness was from Minneapolis and he was describing [Somali militant group] al Shabaab and how they’re being recruited, and how they were being sent overseas and coming back from overseas. And now of course we saw the concern of Mall of America and al Shabaab in Minneapolis, so that was directly on-target.” [King was referring to a recent threat made against the huge Midwestern mall by the terrorist group.]

King’s critics continue to argue that extremism by Muslims is not the only significant threat to American citizens—a concern also raised by groups that voiced displeasure with Obama’s summit. King acknowledged that there’s other threats, but radical extremists professing to be Muslims are of greater concern because of potential international support from terror groups, he argued.

Although the summit was expected to tackle “violent extremism,” it predominantly focused on Muslim extremism, despite vast amounts of research indicating law enforcement considers other radical groups in the US just as dangerous—or even more of a threat—to the community.

According to the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism at the University of Maryland, law enforcement’s chief extremism concern is no longer Islamic extremists, although it was still a major worry.

“Approximately 39 percent of respondents agreed and 28 percent strongly agreed that Islamic extremists were a serious terrorist threat,” the study continued. “In comparison, 52 percent of respondents agreed and 34 percent strongly agreed that sovereign citizens were a serious terrorist threat.”

When it comes to fatalities, those perpetrated by Muslim Americans accounted for seven deaths in 2014, compared to approximately 14,000 murders in the US during that time, according to a report released in February by the Triangle Center on Terrorism and Homeland Security at Duke University. Additionally, since the Sept. 11 attacks, there have been more than 200,000 murders in the country, researchers reported. In 2014, 30 mass shootings killed four or more people, resulting in 136 deaths.

Deaths caused by individuals who adhere to Islam, although just as abhorrent, are relatively miniscule compared to the total number of fatalities in the US annually, the research finds.

“While small numbers of Muslim-Americans continue to be indicted for terrorism-related offenses, the publicly-known cases of domestic plots does not suggest large-scale growth in violent extremism or more sophisticated planning and execution than in recent years,” the report noted.

Yet, Islamic extremism—although Obama didn’t say it outright—happened to dominate the conversation, according to people who attended the summit.

“When the feds say, ‘Oh, we’re going to put on all these panel discussions,’ and they’re all basically overwhelmingly either law enforcement talking about Muslims or Muslims talking about the need to address ideological violence, that sends a very clear message to the media and Muslim communities that Muslim communities pose this special threat,” said Katon of Muslim Advocates. “And study after study has shown that is simply not true.”

Rights groups also take issue with law enforcement utilizing members of the community to root out perceived extremism and essentially singling out people who may have radical thoughts but don’t pose a serious physical threat.

“I think that the intention is probably good, the intention is to prevent violence, but if the government is essentially using teachers and social workers and coaches to gather information that will then be transmitted to the government, then of course that’s problematic—that’s a little more than intelligence gathering,” Hugh Handeyside, staff attorney with the ACLU National Security Project, and a former CIA analyst, told the Press, one day after an appearance at Hofstra University in which he took part in a panel dubbed, “The Globalization of Islamophobia.”

For organizations skeptical of the government’s intentions, the issue goes far deeper than just how Muslims are perceived by their fellow residents, given law enforcement’s murky relationship with the Muslim American community.

“As we’ve seen in other contexts, law enforcement abuses targeting one community will expand to others unless there are clear and specific protections,” Hina Shamsi, director of the ACLU National Security Project, told the Press in an email. “Instead of clear and specific safeguards, the CVE strategy risks treating people, especially young people, as security threats based on vague and virtually meaningless criteria.

“That’s not only stigmatizing, unproductive, and ineffective,” she added, “it alienates the very communities it’s meant to engage.”

Daisy Khan, executive director and co-founder of the New York City-based American Society of Muslim Advancement and an LIU Post graduate, suggested the government focus solely on the terror groups that pose a threat—al Qaeda and ISIS—so as to not alienate the very people they’re hoping will help weed out bad seeds.

“I think they were trying not to stigmatize the religion by calling it an extremism conference and I think maybe it’s time to just call it what it is and have a summit on al Qaeda and ISIS,” Khan, who was recently recognized by the Islamic Center of Long Island for her accomplishments, told the Press. “I think Muslims would rally around that. And when you can feel it and you try to give it a cover and try to frame it in a broader framework, you can’t rally the troops around what the issue really is.”

For her part, Khan is embarking on a months-long project to give Muslim American families the tools they need to counter radical ideology. The project is similar to one Khan’s organization used in Afghanistan in 2009 that successfully got dozens of extremists to lay down their arms, she said.

“It’s meant to protect Muslims from falling prey,” she said. The project, which will become a sort-of digital counter-radical ideology handbook, would make clear that the violent ideology is an abuse of Islam.

“Because right now, Muslims don’t know,” Khan explained. “They think it’s an attack on Islam when people say this is Islamic. Yeah, they [terrorists] are using Islam, but they are distorting it, and we have to reveal that distortion and show people how they’re distorting it.

“And that’s the work that lies ahead.”