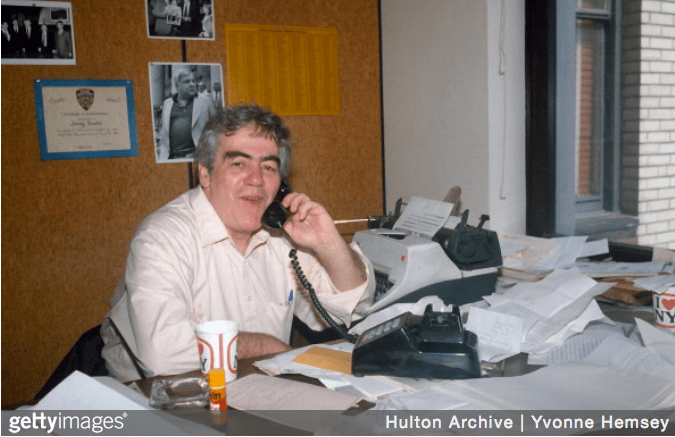

The first time I met Jimmy Breslin at New York Newsday I thought he was sitting down because he already had such a huge reputation I didn’t realize that this living giant of New York City was actually shorter than me. But that didn’t stop me from always looking up to him.

I was ecstatic when my publisher hired him away from the Daily News to join our side of the city’s tabloid war in 1988—even if it was for half a million bucks. Breslin was no Times man, as he’d say, although he did once entice the New York Times‘ Abe Rosenthal to join him at a bar in Queens, proving that some of the colorful characters he chronicled actually existed. Now it’s hard to believe that Breslin no longer exists—he died Sunday at age 88 of pneumonia.

At that first meeting in Newsday’s city room, I wasn’t sure why he seemed to single me out when he said the trouble with young journalists today is that we spent too much time at the gym and not enough time in bars getting the real story. He made going to a health club sound like a dereliction of duty. He urged us to put the phones down and get out into the boroughs, walk up the five flights of stairs and knock on doors.

I already knew about the groundbreaking columns that he had turned in, like when he interviewed the man who actually dug John F. Kennedy’s grave at Arlington National Cemetery and earned $3.01 an hour. Or how as a columnist at the Daily News he was the recipient of the Son of Sam’s letters, which helped lead the cops to the author, David Berkowitz, the serial killer responsible for terrorizing so many young New York women in the summer of 1977. And how he had the presence of mind—and the respect of the men in blue—to write about the policemen who rushed John Lennon to the hospital after the great rock musician had been gunned down outside The Dakota on West 72nd in 1980.

Breslin had a staccato style that was Hemingway-like to my ears, as if I could picture him pounding on the keyboard of an old Smith Corona typewriter. But he also had an eye for detail and a love of language that propelled even his most mundane efforts into something worth reading, because you know, it was Jimmy Breslin, and what he had to say mattered no matter what, whether he was writing about that unique mob boss, Un Occhio, or taking the wind out of a blowhard politician who had turned his pin-striped back on the poor.

Over the years, I’ve enjoyed devouring some of his 20-plus books, particularly The Good Rat, about a murder trial involving two cops, and Can’t Anybody Here Play This Game, about the hapless 1962 Mets under beleaguered manager Casey Stengel. I could always hear his distinctive voice, as if he were on the next barstool telling a tale while chomping on a cigar. But I remain a bigger fan of his columns, because that daily deadline pressure brought out the fighter in him—and he was afraid of nothing and no one.

In pursuit of the story behind the headlines, he got severely beaten up at Crown Heights during a race riot in 1991. He was left standing in his underwear holding his press badge, with a black eye and a bloody lip. But the city wasn’t his only beat. He covered the world, too. I learned from his obit that he was standing five feet away from Robert F. Kennedy when the great liberal Senator from New York was shot in Los Angeles after winning the California Democratic primary in 1968. I had missed his column on Three Mile Island in 1979 when it was on the verge of a meltdown that would have had apocalyptic consequences. Breslin didn’t hunker down in a bunker. Instead, he headed straight for the overheating reactor just south of Harrisburg, Penn. He reportedly told his loyal New York driver—Breslin never got his own license—to “step on it—it could be the end of Pennsylvania!”

His path through the harrowed halls of the Fourth Estate took him from the old Long Island Press in Jamaica, Queens, where he was a copy boy, to the New York Journal-American, where he was a sports writer, to the New York Herald Tribune, where he started writing a column, and later to the New York Post, New York Magazine and the Daily News, where I first found him. With Tom Wolfe, Gay Talese and Hunter S. Thompson, he was one of the pioneers of New Journalism in the 1970s, practitioners of a unique blend of subjectivity and objectivity that never compromised on integrity—and my inspiration as a journalist. In recognition of his career, Breslin won a Pulitzer Prize in 1986 “for columns which consistently champion ordinary citizens,” the board explained. But he didn’t rest on his laurels. Not for a moment. He still had many more stories to tell, with hundreds of thousands of words boiling within him, waiting for the right moment to hit the page.

During my time at Newsday, I never edited Breslin, but I did know some copyeditors whom he’d bark at when he was on deadline and didn’t like them messing up his lede. I knew he was cantankerous, and didn’t suffer fools, but I wish he hadn’t hurled a racist slur at the young Korean-American woman reporter who had sent him an in-house message criticizing one of his columns for being sexist. His politically incorrect attitude led to his brief suspension in 1990. As he said in an apology to the staff: “I am not good and once again I can prove it.”

That was the flipside of his larger-than-life persona. He could share a drink with Norman Mailer, no slouch when it comes to big egos, and regard himself as the great American novelist’s peer—they did run a Don Quixote-like municipal campaign together in 1969, with Mailer aiming to become mayor and Breslin City Council president (their big issue was to make New York City the 51st state). But he would also venture into the farthest reaches of the Bronx, Brooklyn and Queens to shine the light on the unsung New Yorkers who make the city actually function—or whose lives were worth telling when tragedy struck close to home. He himself had come out of a rough and tumble world.

While he was still a kid in Queens, his alcoholic dad abandoned Breslin’s family. From that low point, Breslin rose to the heights of the city. And he did it without fear or favor.

Breslin called it the way he saw it—and we hung on every word.