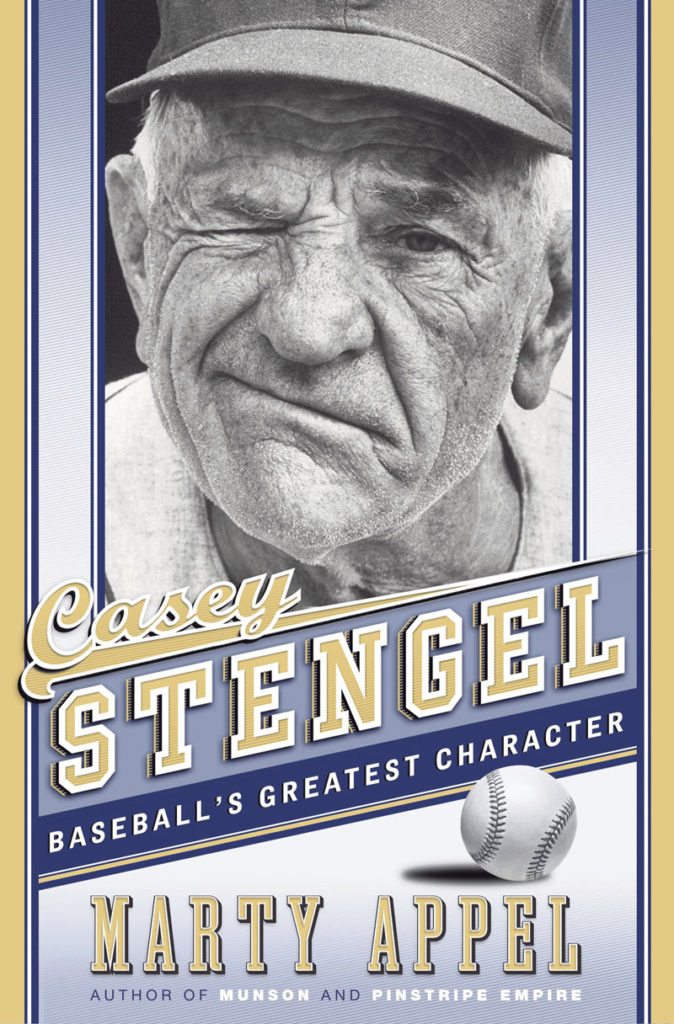

One of the takeaways from Marty Appel’s fascinating Casey Stengel: Baseball’s Greatest Character (Doubleday) is how closely Stengel’s career trajectory resembles Joe Torre’s.

One of the takeaways from Marty Appel’s fascinating Casey Stengel: Baseball’s Greatest Character (Doubleday) is how closely Stengel’s career trajectory resembles Joe Torre’s.

Stengel and Torre played in the major leagues and then launched relatively undistinguished baseball managerial careers before being named manager of the New York Yankees. Moreover, both men were in their late 50s when they took the job, which would make them legendary figures.

Appel, the Yankees’ former public relations director, will be speaking and signing his just-published and critically well-received Stengel biography on Monday, April 24, at 7 p.m. at Book Revue, 313 New York Ave., Huntington.

“In 1996, along came Joe Torre to manage the Yankees,” writes Appel. “Like Casey, he [Torre] had mediocre results with bad National League teams and then suddenly found himself rolling in the riches of talented players. His [Torre’s] Yankee success—six American League pennants, four of them leading to world championships—thrust him into the Hall of Fame, just as it had Casey.”

Torre’s era as Yankees manager coincided with the prime years of future Hall of Famers, such as Derek Jeter and Mariano Rivera, while Stengel benefited from filling out a line-up card that included names such as Mickey Mantle and Yogi Berra, who were subsequently immortalized at Baseball’s Hall of Fame in Cooperstown. But few imagined when Torre and Stengel were first appointed the Yankees’ skipper the incredible success their teams would achieve. In fact, both appointments were criticized by many baseball writers at the time, with Torre seen as “clueless” Joe and Stengel portrayed as an entertaining “clown,” Appel notes.

Charles Dillon Stengel (1890-1975), whose nickname Casey arose from his Kansas City roots, had managed the Oakland Oaks to a Pacific Coast League championship in 1948. Stengel soon afterwards debated with his wife, Edna, whether to accept the position of New York Yankees’ manager. The Yankees, with Stengel at the helm, went on to win the World Series in five straight years (1949-53) and eventually secured seven World Series titles during his time there, winning championships in 1956 and 1958, too. Nevertheless, the Yankees relieved Stengel of his duties in 1960. As luck would have it, another New York team, the Mets, were opening up for business only two years later.

“Casey’s work with the Mets, though, will be difficult to duplicate,” Appel states. “Indeed, few expansion teams in any sport have tried the formula—a quotable, fan-popular man who would charm the press and deflect attention away from ineptness on the field. Today’s expansion teams are better stocked with players and better able to improve their situations quickly. There may never again be a 1962 Mets.” Given that the 1962 Mets won 40 games and lost 120, that’s a good thing. Stengel retired as Mets manager in 1965 and was inducted into baseball’s Hall of Fame in 1966.

Benefiting from access to Edna Stengel’s unpublished memoir, which was written in the late 1950s, Appel’s book is also filled with memorable anecdotes about the youthful Stengel, who was found to have been the “owner” of eight beers within an hour by a team management representative who was keeping tabs on its rowdier players. Stengel acknowledged to his bosses he may have owned four beers within that time frame. Fast forward to the middle-aged Stengel, and he’s telling the Yankees’ players to be in bed by midnight and up by 7:30 a.m., perhaps having learned as a young man that nothing good happens after midnight.

Mike Barry can be reached at mfbarry@optonline.net. The views expressed in this column are not necessarily those of the publisher or Anton Media Group.