When F. Scott Fitzgerald maintained that there are no second acts in American life, he may have been thinking of himself. By age 40. Fitzgerald, whose fiction had defined the Jazz Age, seemed washed up: His novels forgotten, his new efforts unfinished, his alcoholism worsening, his wife Zelda suffering from mental illness; even Hollywood wanted nothing to do with him.

When F. Scott Fitzgerald maintained that there are no second acts in American life, he may have been thinking of himself. By age 40. Fitzgerald, whose fiction had defined the Jazz Age, seemed washed up: His novels forgotten, his new efforts unfinished, his alcoholism worsening, his wife Zelda suffering from mental illness; even Hollywood wanted nothing to do with him.

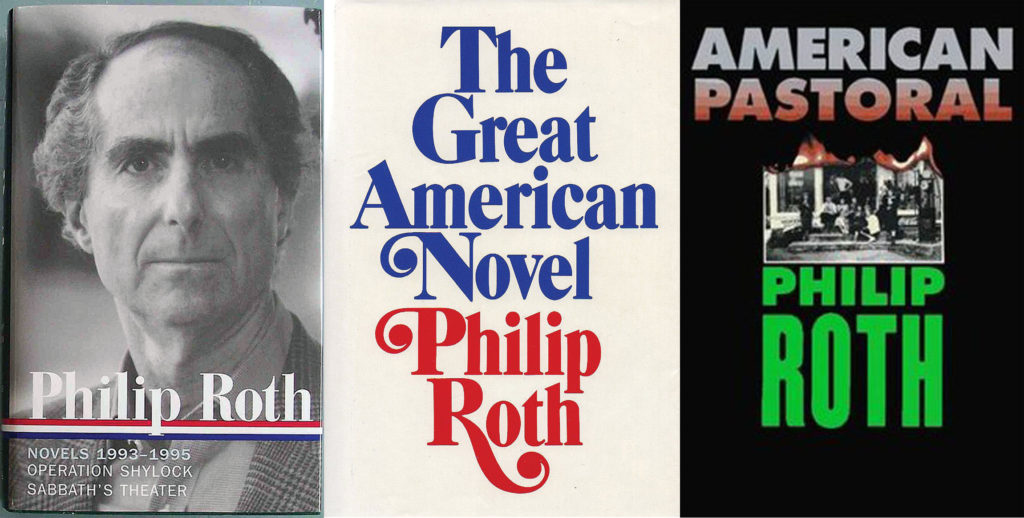

By the 1980s, Philip Roth seemed to be stuck in his own rut. The novelist had his own health problems, plus his fiction was mired in the autographical mode. Did the reading public really need more novels about college professors and their woman problems? Or another novel about the trials of a famous novelist? Roth, according to biographers, regrouped and took stock.

With The Counterlife, his career took a new and inventive turn. As he aged, Roth was even more prolific, matching his friend John Updike novel for novel as these two, among others (notably Tom Wolfe) tried to inject some humanism into the gone-mad American scene. Roth was prolific. As with Updike, he had his hits and misses.

Roth got out of the gate quickly with Goodbye, Columbus, a peerless novella about Neil Krugman, a young Newark librarian and his ill-fated romance with a well-heeled Jewish girl from a tony suburb. The working class met the nouveau riche and there was little doubt to which side Roth was on. What followed were two well-crafted novels, Letting Go (1960), the obligatory coming of age novel of middle-class professionals and When She Was Good (1967), a send-up of Middle America life gone pscyho.

Roth got out of the gate quickly with Goodbye, Columbus, a peerless novella about Neil Krugman, a young Newark librarian and his ill-fated romance with a well-heeled Jewish girl from a tony suburb. The working class met the nouveau riche and there was little doubt to which side Roth was on. What followed were two well-crafted novels, Letting Go (1960), the obligatory coming of age novel of middle-class professionals and When She Was Good (1967), a send-up of Middle America life gone pscyho.

In 1969, Roth hit the jackpot with Portnoy’s Complaint. Published at the height of the sexual revolution, Portnoy was a phenomenon. It made Roth rich and famous, but it may have proved to be a burden, too. In his youth, Roth devoured the novels of Thomas Wolfe. The latter had Eugene Gant as the alter ego/hero. Roth, similarly invented Nathan Zuckerman the artist/hero contending with the modern world. It got off to a slow start with Zuckerman Unbound, about a novelist who published a famous book, Carnovsky (think Portnoy’s Complaint). Instead of novel after novel about a novelist, Roth began using Zuckerman as an observer such as works as The Counterlife, Operation Shylock, I Married A Communist and American Pastoral. Again, there were hits and misses.

Roth’s second act was in full swing. A 2005 novel, The Plot Against America, in which the famed aviator and America First firebrand Charles Lindbergh is elected president, was both a sensation, but also, to me, a flight of paranoia somewhere north of the stratosphere. A purpose of this administration was to break up the nation’s tightly-knit Jewish communities (such as Newark’s North Side) and disperse its inhabitants across the country. Walter Winchell, the crusading anti-Lindbergh broadcaster, is assassinated on a campaign stop in Kentucky. A Newark family is terrorized while traveling through West Virginia. It was an alarming read, but, again, paranoia at its most extreme.

Several years ago, Roth appeared at a forum at Queens College. My dilatory ways preventing me from attending, but had I done so, it would have gone like this: “Mr. Roth, been reading you for decades, but Plot Against America? I know both Kentucky and West Virginia well. Family from there. Every Saturday, Jews go to and from synagogues in Charleston, Lexington and Louisville in peace. It’s not that bad!” It was just as well I didn’t make it. A Plot Against America was an alarming read, but hardly an accurate picture of America in the early 1940s.

Several years ago, Roth appeared at a forum at Queens College. My dilatory ways preventing me from attending, but had I done so, it would have gone like this: “Mr. Roth, been reading you for decades, but Plot Against America? I know both Kentucky and West Virginia well. Family from there. Every Saturday, Jews go to and from synagogues in Charleston, Lexington and Louisville in peace. It’s not that bad!” It was just as well I didn’t make it. A Plot Against America was an alarming read, but hardly an accurate picture of America in the early 1940s.

American Pastoral, on the other hand, redeems much of the Roth canon. Here, Roth finally writes his demise of civilization tome. If Saul Bellow’s Mr. Sammler’s Planet was the ultimate 1960s novel, then American Pastoral is the perfect early 1970s fiction statement. It was if Roth was updating his longtime master. Bellow’s novel portrayed a Holocaust survivor observing—but not despairing—of late 1960s Upper West Side New York: petty crime, violent crime, promiscuous youth, obscene college students. Roth’s 70s America is wracked by opposition to the Vietnam War, violence being perpetrated by middle class and upper-class college students, all vowing to “bring the war home” with thousands of terrorist attacks taking place across the country. The novel is about widespread moral rot, namely that arresting picture of a suburban nation packing cinemas for the most degrading moviemaking possible. Packed houses for X-rated films! Where was the good old Newark of the 1940s? Prosperity, as William Faulkner might put it, isn’t always good for people.

The novel has other themes: Manhood and Newark. Seymour “Swede” Levov is Roth’s most realized fictional character. A high school football and basketball star at Newark’s Weequahic High School, the Swede’s World War II-era athletic exploits helps to get people’s minds from the killing fields in Europe and Asia—and the inevitable knock on the door.

Manhood comes hard for Roth’s characters. Krugman makes it back to the Newark library, but others fall way short. Alexander Portnoy can’t get off the psychiatrist’s couch. Peter Tarnopol, in My Life As A Man, is a wife-beater. Zuckerman and another intellectual alter-ego, David Kepesh all successful enough, but they leave nothing behind. Mickey Sabbath of Sabbath’s Theatre considers suicide but backs down. This angry man doesn’t want to leave a world where there is still “so much to hate.” (Yes, he mourns a lost brother, but that isn’t reason enough.) Simon Wexler in The Humbling does commit suicide once his acting skills have left him and yet another life of debauchery isn’t enough. Finally, Bucky Cantor from Nemesis, a valentine to the mid-1940s Newark, is another bundle of self-pity. A polio outbreak is a theme of the novel. Cantor is victimized. He gives up on life. A high school athlete, Cantor could have been athletic director at Weequahic. Worse, he breaks up with his ever-faithful girlfriend, preferring to wallow away his life at a post office clerk.

Manhood comes hard for Roth’s characters. Krugman makes it back to the Newark library, but others fall way short. Alexander Portnoy can’t get off the psychiatrist’s couch. Peter Tarnopol, in My Life As A Man, is a wife-beater. Zuckerman and another intellectual alter-ego, David Kepesh all successful enough, but they leave nothing behind. Mickey Sabbath of Sabbath’s Theatre considers suicide but backs down. This angry man doesn’t want to leave a world where there is still “so much to hate.” (Yes, he mourns a lost brother, but that isn’t reason enough.) Simon Wexler in The Humbling does commit suicide once his acting skills have left him and yet another life of debauchery isn’t enough. Finally, Bucky Cantor from Nemesis, a valentine to the mid-1940s Newark, is another bundle of self-pity. A polio outbreak is a theme of the novel. Cantor is victimized. He gives up on life. A high school athlete, Cantor could have been athletic director at Weequahic. Worse, he breaks up with his ever-faithful girlfriend, preferring to wallow away his life at a post office clerk.

The Swede, on the other hand, is Roth’s most heroic protagonist. He marries a former Miss New Jersey, runs a successful ladies’ glove business and is the father of a young girl. The daughter runs away from New Jersey horse country to the Lower East Side, where she becomes a Patty Heart-like radical bombing a local post office, killing, in the process, an elderly physician. Swede has achieved manhood, now, against all odds, he must fight to keep it. Which he does but remarrying after the inevitable divorce and siring a young son. It’s a struggle which summons up all the will he can muster.

Swede, as noted, is another Newark native. Roth, likewise, is inexorably linked to that city. Newark makes an appearance in numerous works, often as a location for much nostalgia, with retirees, now lost in Florida, forever mourning the passing of a once-pleasant city. “Phil, we never had so much fun as when you boys were younger,” an elderly woman laments. The old Newark was poor, but safe; it had, above all, a sense of community.

Swede, as noted, is another Newark native. Roth, likewise, is inexorably linked to that city. Newark makes an appearance in numerous works, often as a location for much nostalgia, with retirees, now lost in Florida, forever mourning the passing of a once-pleasant city. “Phil, we never had so much fun as when you boys were younger,” an elderly woman laments. The old Newark was poor, but safe; it had, above all, a sense of community.

Such reflections were moving, but Roth seemed to be dancing around the subject. The signal event in the city’s 352- year history are the five days of rioting that took place that took place from Aug. 12-17, 1967, an orgy of barbarism that the city has never recovered from. Roth’s treatment of the riots in American Pastoral was calm and even-handed, from the trials of certain residents to the response from South Jersey farm boys who filled the ranks of the state National Guard.

With Newark, there are no happy endings. The city’s decline began in the early 1950s, with many key industries leaving the city. By 1967, Newark was a time bomb ready to detonate. Roth was balanced, but there is no talk of renaissance, either. “It will be 500 years before things get better!” a despairing retiree blurts out. It’s always salutatory to be told something you already know. 500 years. Newark—or America? Or both?

Roth’s canon had glaring faults. As with Updike, he published too often. Take some time in between novels. His rage gained him fans happy to see WASP America get its comeuppance. Too often, it got ugly. When Roth was down on certain ethnic groups—Italian-Americans, Cuban-Americans, Scotch-Irish Appalachia, Wall Street WASPs—he put female characters from those stock in the most degrading situations possible. If ever a novelist needed a blue pencil, it was Roth. With American Pastoral, we’ll remember the man at his best.