FP Memorial Day parade marshal still serving his country after seeing time in three different wars

“They gave the world new science, literature, art, industry, and economic strength unparalleled in the long curve of history. As they now reach the twilight of their adventurous and productive lives, they remain, for the most part, exceptionally modest. They have so many stories to tell, stories that in many cases they have never told before, because in a deep sense they didn’t think that what they were doing was that special, because everyone else was doing it too.” – Tom Brokaw’s The Greatest Generation

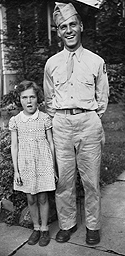

If there is one quote that could be used to describe the life Vincent DeMartino has led, this would be it. A veteran of World War II, the Korean and Vietnam wars, DeMartino was chosen to be the parade marshal for the Floral Park Memorial Day Parade. Barely a few inches above five feet tall, DeMartino is an unassuming man whose lack of height is more than made up for in the character he forged on the battlefronts of Europe and Southeast Asia.

The flattop he sports is the only indication of the 25 years of military service he has under his belt and the relationship with the armed services he’s enjoyed by working with veterans in various capacities ever since he retired from active duty 40 years ago. Quite a feat when you consider the fact that it’s been 68 years since the Valley Stream native first enlisted in the Army as a self-assured 17-year-old. It’s an accomplishment that he’s pretty matter-of-fact about.

Heading Off To War

“Everyone was [enlisting]. It was wartime and they wouldn’t let me play football in high school, so I thought I’d go into the service,” he explained. “I had to get my parents’ permission and I ended up in the enlisted reserve. When I turned 18 in December 1943, I got my call-up and got a deferment from my high school guidance counselor.” After a brief stop in Fort Dix, the scrappy Long Islander wound up in Fort Indiantown Gap, PA where he took basic training with the 95th Infantry Division. By July 1944, DeMartino and his fellow grunts were being shipped off to Europe, with stops in England and France. By the end of the year, his division was a major component of the Battle of the Bulge, where American troops spearheaded a crucial Allied victory over a significant five-week German offensive in the Ardennes mountain region. With more than 80,000 American casualties and almost 20,000 fatalities, it’s considered by many to be the biggest and bloodiest battle of World War II and an experience he remembers vividly.

“We held the Third Army front at that time at the Siegfried Line. There was a pillbox over there that they shelled every morning and we’d just knock the snow off of it,” DeMartino recalled. “We were lucky there, too, because if the Germans knew there was a half-ass division there, it would have been a different story.” He wound up staying with the 95th Infantry Division through the end of the European campaign. Upon returning stateside, he was sent down to Mississippi, awaiting orders to be part of a third wave of troops invading Japan, a battle plan that was scuttled after nuclear bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. When the war ended, the young infantryman’s division was broken up and he was transferred to Camp Atterbury, Ind., where he worked in the dental portion of the discharge center. His discharge came in February 1946, two years to the date that he went in.

Korea And Vietnam

In the two years following his discharge, the young veteran returned to Valley Stream Central High School, earned his diploma and went to work in his parents’ grocery store, selling fruits and vegetables in his hometown. The lure of military life convinced DeMartino to re-enlist, but rather than go back into the infantry, he decided “…that I wanted to learn something this time, so I went to mechanic’s school in Atlanta.” His assignment following graduation took him to GHQ in Tokyo, where he landed in a signal battalion as a mechanic working on trucks. When war broke out in 1950, he and nine other soldiers working in the motor pool were transferred to Korea in July, where they were supposed to drive for some troops. It didn’t quite work out that way.

“We ended up on the Pusan Perimeter, so we didn’t know if we were staying or going. Plus we were a bastard outfit, meaning we weren’t attached to anybody. They formed us into a company called GHQ Long Lines. We rehabilitated all the telephone lines in Korea as well as working on all the repeater and transmitter stations,” DeMartino explained. “I was just a mechanic and a driver at that time and there were times when I had to travel 100 miles a day trying to find parts to keep the vehicles going. Every ordinance company I saw, I’d stop by with a piece of paper and get them that way. It was kind of hairy at times because I always went by myself. We were told we were only going to be there 30 days, but 13 months later we were back in Tokyo, getting ready to be sent home.”

The year-plus spent serving during this first tour of Southeast Asia, didn’t provide for the happiest of memories, DeMartino admits. As the weather grew colder, he and his fellow soldiers were forced to purchase clothes on the black market as the Army had only provided them with uniforms suited for the summer months. There were scenarios not too far removed from those portrayed in the M.A.S.H. television series. Anecdotes abound of trucks getting mired in rice paddies, refilling canteens from water sources teeming with maggots and fighting the cold by wearing two sets of clothing and huddling around the potbelly stove found in each tent while trying to stave off frostbite.

When DeMartino wound up in Vietnam from 1968-1970, things weren’t much better. “To me the Vietnam conflict was like the old cowboys and Indians movies. The post was here, the troops were there and the Indians were outside. You couldn’t go out at night. You had to stay right in that compound,” he said shaking his head. “I got there in’68, right after Tet. Before Tet, guys were allowed to go outside the gate. After that, they weren’t allowed to go outside the gate anymore. In fact, when another unit was coming back [from patrol], they were only a little ways from the gate when they got hit. This was also not a happy place. It was an altogether different war.”

With the unique perspective gleaned from having served in three wars, DeMartino admits that the overall outcomes of his last two go-rounds were affected by the military’s lack of preparation. And it’s a situation that’s seemingly carried on into the present day. “When the Korean War broke out, all the divisions were understaffed and they had World War II weapons. A lot of it was obsolete and inoperable. They were understaffed in their units, because they cut down the army just like they want to do now,” DeMartino said. “They want to cut down the services. You don’t go to war with 140,000 people. If you ever go to [Gen. Douglas] MacArthur’s museum in Norfolk, Va., he has a plaque on the wall that says, ‘If you don’t go to war to win, you don’t go.’ As far as I’m concerned we lost the Korean War, the Vietnam War and the one we’ve got here. We’re not gaining anything.”

Brothers In Arms

When the octogenarian pulls out a weathered brown photo album, the military stripes and medals plastered on the cover are the first things that grab your attention. Among his keepsakes are a unit commendation Patton awarded to the 95th Infantry for capturing a Germany fortress in the southern French city of Metz and his Combat Infantry badge. Numerous photos shot at various locales ranging from Indiana’s Camp Atterbury to New Alresford, England and parts of Germany are sprinkled throughout. Upon hearing laudatory comments and questions as to what he’s told his family about his wartime exploits, DeMartino responds with the unabashed modesty that characterizes many of his generation who served. “I don’t talk about it much. I was no hero. I just did what I was supposed to do.”

Once he filed his final round of discharge papers in 1970, DeMartino settled his family in his wife’s hometown of Floral Park, where his civilian life found him working as an air conditioning parts manager in Flushing until his early 1980s retirement. Through it all, he’s maintained a relationship with the military over the four-plus decades following his discharge. Nowadays, he maintains a schedule impressive for someone half his age, never mind someone in their mid-80s. Twice a week he heads out to his office in the Northport Veterans Administration Hospital where he helps out veterans with benefits-related paperwork. In addition, DeMartino is the past commander and current chaplain of Albertson VFW Post 5253, is the hospital chairman for the county at the VFW and serves in the U.S. Volunteers, a veterans group that provides escorts and aids in ceremonies for veterans funerals. All this doesn’t even include the two monthly Saturday bingo games he helps out with over at the St. Alban’s Veterans Administration Hospital.

DeMartino’s support of the military is such that when the United States invaded the Caribbean island nation of Grenada in 1983, he attempted to re-enlist, only to be turned away. “I thought about going back in, but they wouldn’t take me,” he recalled with a laugh. “The body might not be worth it, but the mind is still there, [even if] I might not be able to run five miles a day anymore. I guess it’s the uniform that brings me back.” When you ask whether there’s a generation gap between younger veterans who may have served in recent campaigns in Afghanistan or Iraq, DeMartino smiles, insisting that time served is the only bridge he and these ex-servicemen and women need. “I think of them like they’re my children out there. I’d like to be with them. It never leaves you. Some guys it does, but to me it doesn’t for as long as I’ve been out, which is 40 years. If they let me go back in tomorrow, I’d go.”