When Gen. George Washington made his victory lap of Long Island in April 1790, he sounded almost like any annoyed commuter today.

“Uneven ground and none of it of the first quality,” he wrote in his journal, “but intermixed in places with pebble stone.” He complained that “the weather was so dull & at times Rainy that we lost much of the pleasures of the ride.”

But overall, Washington took it in stride. For one thing, his country was at peace. He started his tour in New Utrecht, dining “at the house of a Mr. Barre…the man was obliging but little else recommended it.”

The next day he watered his horses in Hempstead before stopping for dinner at the Zebulon Ketcham house in Copiague and spending the night at Squire Isaac Thompson’s home, Sagtikos Manor, in West Bay Shore. The next morning, Washington “halted awhile” at Samuel Green’s place in West Sayville before dining at Hart’s Tavern in Patchogue. He headed to Setauket the next day and spent the night at a “tolerably” decent tavern owned by Austin Roe, who had played a key role in his Revolutionary War intelligence network known as the Culper Spy Ring.

Setting out early the following morning, he fed his horses at “a decent house” owned by “Widow Blydenburgh” in Smithtown before dining at “a tolerably good” house owned by “a Widow Platt” in Huntington and stopping for the night in Oyster Bay at Daniel Young’s homestead.

For his last day on Long Island Washington got up at 6 a.m., and later had breakfast in Roslyn at Hendrick Onderdonk’s spread, getting a tour of his grist and paper mills (making a sheet by hand, family legend has it). For dinner he stopped in Flushing before riding to Brooklyn, where he took the ferry back to Manhattan as the sun was setting. Not bad for a 58-year-old Virginia gentleman who’d become president the year before.

And what a far cry from those anxious days the general had faced in July 1776, when things looked a lot more dire—and crossing the East River was a dangerous move in the face of enemy fire.

Back then, Washington could do nothing to stop Vice Admiral Richard “Black Dick” Howe from sailing the British war fleet into the Lower Hudson and anchoring off Staten Island, where his brother, Lord William Howe, amassed some 32,000 soldiers. Facing them from Brooklyn Heights were some 4,000 “rebel” troops commanded by Nathanael Greene, whom Washington considered his best units. On paper the Americans numbered 20,000 men but most of them were sick, poorly trained and badly equipped.

On Aug. 22, Admiral Howe ferried his brother’s troops across the Narrows to Long Island. Greene was so ill that Washington had to replace him right before the battle. He put New Hampshire’s John Sullivan in charge first, but Sullivan didn’t prove up to the task so Washington appointed Connecticut’s Israel Putnam, who hardly knew the terrain. Greene, whose legacy today is Fort Greene in Brooklyn, had known the lay of the land very well, since he had been furiously building fortifications between Red Hook and Wallabout Bay, the future home of the Brooklyn Naval Yard.

Putnam’s ignorance of Brooklyn proved costly indeed. There were four passes to defend but he protected only three, and so with help from local Tories—and Queens was full of them—the British moved their troops through the Jamaica Pass on the night of Aug. 26, roughly close to where the Jackie Robinson Parkway runs into Jamaica Avenue today.

When dawn came, the Americans were quickly outflanked. “Our men fought with more than Roman virtue,” wrote an American soldier later, but the rout was a disaster. Washington would have lost his army had it not been for Mordecai Gist’s 250 Marylanders, who valiantly held the line in the Gowanus marsh, prompting the general, who was watching from afar to turn to Putnam and say, “Good God, what brave fellows I must this day lose.”

As historians have written since, just when all hope looked lost for the Americans, the wind changed in the Battle of Long Island, preventing Admiral Howe from sailing up the East River and wreaking havoc. Instead, under cover of night and fog, Washington was able to evacuate 9,000 men and material before the British knew they were gone.

Not that Washington was in the clear. There would be the harsh winter at Valley Forge, the demoralizing defeat at the Brandywine River in Chad’s Ford, Penn., when yet again, Tory sympathizers were able to lead the British army to a crossing that Washington didn’t know about, and many other arduous battles.

But somehow he always came through. His horse was shot out from under him three times in the French and Indian War and later in the same conflict he even found himself caught in the crossfire of his own troops as dusk was falling and he was yelling, “Cease fire!” at the top of his lungs. So Washington never lost faith that he’d find a way to prevail.

Behind Enemy Lines

With his enemy firmly ensconced in New York, Washington craved reliable intelligence so he could know what they were up to. In September 1776, Nathan Hale, who had volunteered to spy for the cause, was caught in Huntington. Before the British hung him in Manhattan, the 21-year-old American uttered his famous last words: “I only regret that I have but one life to lose for my country.”

In mid-1778, Washington assigned Benjamin Tallmadge, a young Long Island cavalry officer from Setauket, the difficult task of creating a spy ring. Tallmadge entrusted Abraham Woodhull, a farmer whom he’d known since childhood, and Caleb Brewster, who commanded whaleboats that harassed British and Tory shipping on the Sound. Tallmadge used the code name “John Bolton,” Woodhull adopted the name “Samuel Culper.”

Besides aliases, Washington’s covert network used dead drops, invisible ink, secret signals and relayed coded messages published in newspapers about British activities in occupied New York City.

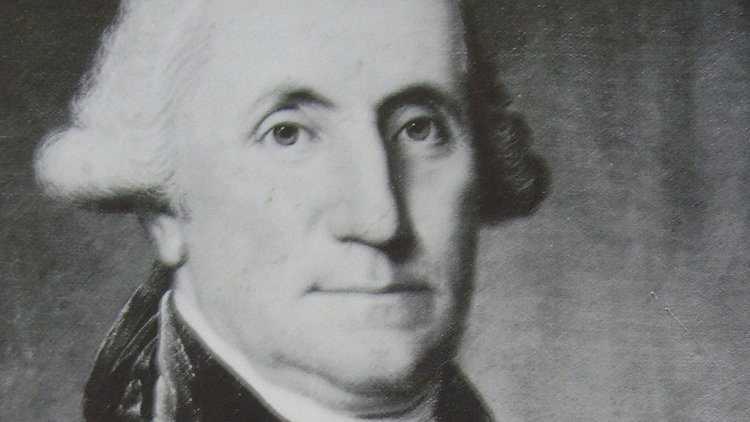

For more than a century the identity of “Samuel Culper Jr.” remained a mystery—Washington didn’t even know some of his top spies’ identities—until Long Island historian Morton Pennypacker matched “Culper Jr.’s” letters to Washington with the handwriting of an obscure Oyster Bay merchant named Robert Townsend. He announced his discovery at a meeting of the New York State Historical Society on Sept. 27, 1930.

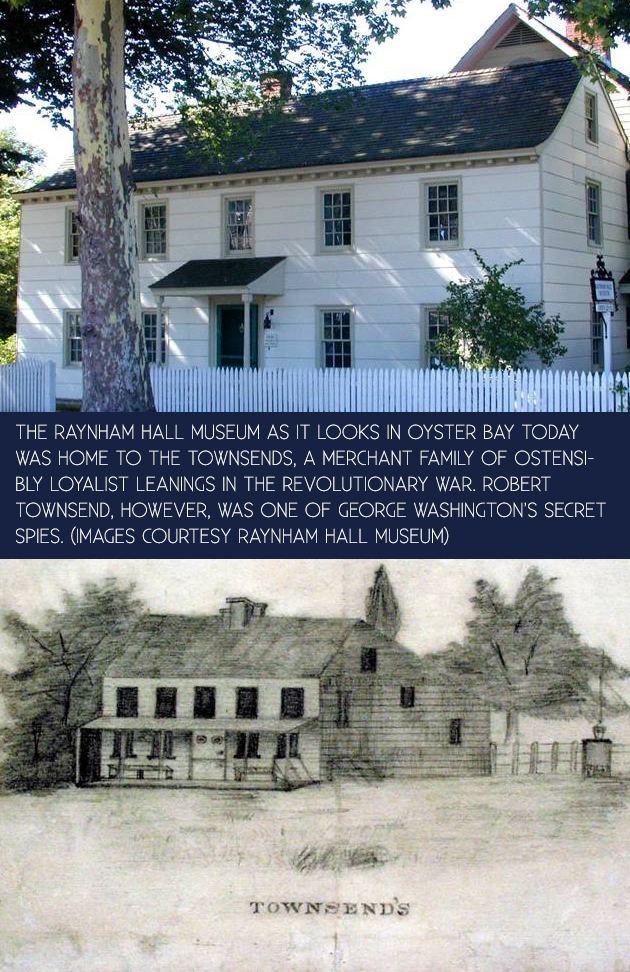

Townsend had taken his greatest secret to his grave in 1838. But his historic house remains today: Raynham Hall Museum in Oyster Bay. Townsend led his double life while British officers occupied his home. It still “has a very strong presence in the paranormal community as one of the most haunted houses in Long Island,” says a museum official.

Certainly something intense was happening in that very crowded house when Townsend was alive. A British colonel staying there was courting Townsend’s sister while he was still engaged to a woman back in England.

Townsend was “an extremely complex man,” observes Alexander Rose, author of Washington’s Spies, a book about the Culper Ring that AMC is turning into a pilot for a potential dramatic series. “His immediate family were Loyalist, and so it must have been very difficult for him to break with them and spy for Washington. His reasons were partly religious, partly patriotic, partly self-interested, and partly because he was annoyed about the practical aspects of British military occupation.”

Washington never knew that Townsend was the man who frequented the coffeehouses and saloons in Manhattan in his disguise as a Tory merchant working for his father’s Oyster Bay business and overheard British officers discussing their war plans.

But the general certainly valued the information the Culper Ring brought him as he later wrote to Tallmadge in two letters now in Stony Brook University’s prized collection of special archives. Currently, The Three Village Historical Society has an exhibit devoted to the spy ring.

Every time people visit the Montauk Lighthouse they can also thank George Washington’s foresight, because he pressed Congress to appropriate the money for it in 1793 but never saw it completed.

As we honor America’s independence this July, let’s not forget Washington’s orders to his troops in New York, supposedly delivered before the Battle of Long Island began, when he spelled out in no uncertain terms what was at stake:

“The fate of unborn millions will now depend, under God, on the courage and conduct of this army. Our cruel and unrelenting enemy leaves us only the choice of a brave resistance, or the most abject submission. We have, therefore, to resolve to conquer, or to die…. Liberty, property, life, and honor are all at stake; upon your courage and conduct rest the hopes of our bleeding and insulted country. Our wives, children, and parents expect safety from us alone, and they have every reason to believe that Heaven will crown with success so just a cause.”

The general trusted that Providence would smile on him, as it had so many times before, and though the outcome he sought in 1776 took many years to achieve, he was lucky it did—as we are today.