Little Unqua is one of the most interesting of the Jones/Floyd-Jones mansions. The Native American word “Unqua” means “far away,” and it was so named  because it was the most easterly of the family’s mansions. It was little only because it was smaller than the larger Unqua mansion that stood facing today’s John Burns Park.

because it was the most easterly of the family’s mansions. It was little only because it was smaller than the larger Unqua mansion that stood facing today’s John Burns Park.

Little Unqua was built in 1861 by Edward Floyd-Jones, who was a New York State Senator and Queens County Supervisor, marching to the same political drum as his first cousins David Richard, a Lieutenant Governor, and Elbert, a New York State Assemblyman. Edward built both Unqua and Little Unqua and lived in both at various times. In 1867, his daughter Louise was born and inherited the mansion and property when she married Conde Thorn in 1889. Her husband died in 1944 and she remained on her estate until her death in 1961. Toward the end of her life, Louise became the center of a multi-faceted discussion concerning her property.

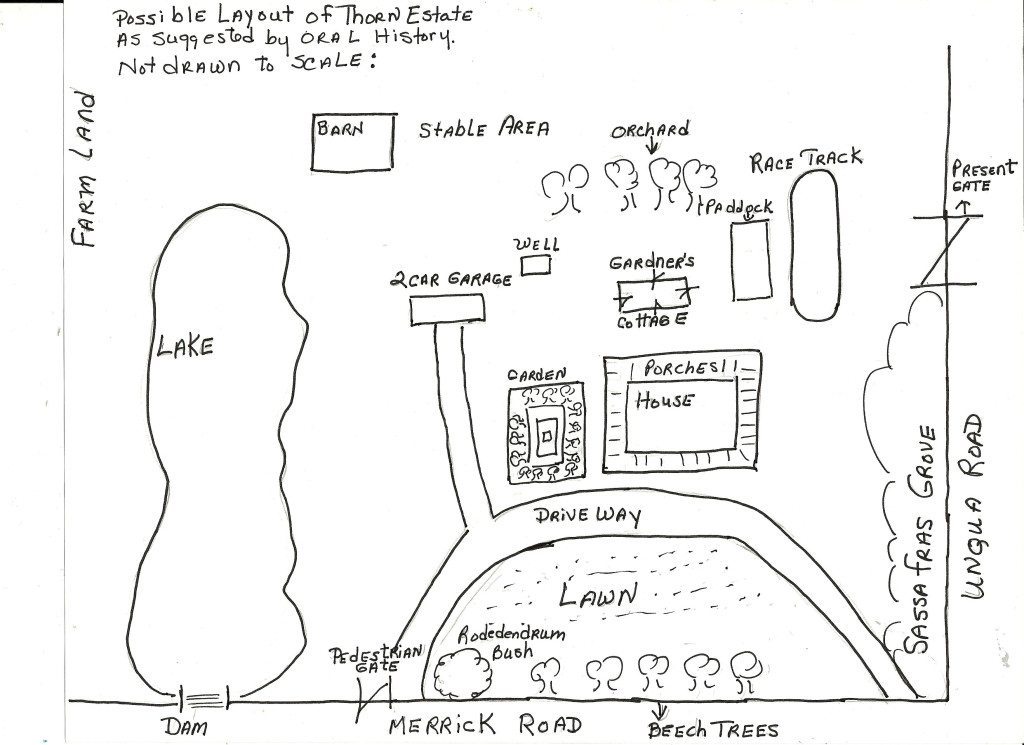

We don’t have detailed information about most of Massapequa’s mansions, but we know quite a bit about Little Unqua, thanks to the efforts of former Historical Society Trustee Barbara Fisher, who interviewed John Nolan, who had worked on the estate as a teenager. He described the house as large, with two sets of porches, one over the other, painted a grayish blue, not as pretentious as some of the older mansions that had existed in the Massapequas. The building faced Merrick Road just west of Unqua Road. There was a circular driveway in front that led in from the Unqua-Merrick corner and exited to the west near Unqua Lake. To the right of the house was a formal garden with cedar trees and a variety of flowers and plants. Nolan indicated there was a gardener’s cottage behind the house and a garage to the west. A barn and a stable were situated at the northwest, near the lake. A paddock with horses was located toward the rear of the property, and a riding track was maintained at the northeast corner. Nolan worked there in 1957, when Louise was 90 years old. He remembered that she was mentally sharp but fragile, and was cared for by her gardener and her daughter, who apparently managed the estate.

What Nolan did not mention—probably because he was too young to appreciate the issue—was the maelstrom that swirled around this prime piece of real estate in the late 1950s. The Massapequas were developing rapidly and every bit of empty space was being filled or repurposed. Several suitors were after Little Unqua; the Board of Education wanted to build a school on the northeast part of the property; the Chamber of Commerce was lobbying for a hospital on the site; the Nassau Shores Garden Club felt it was an ideal location for an art museum and cultural center; several real estate developers submitted plans for either private houses, an apartment complex or a shopping center. All of these proposals were appropriate on their face, but the interested parties had to contend with Louise’s occupancy of Little Unqua. She had expressed her disdain at the development of the Massapequas and felt a park of some sort should replace her estate, but only after her death.

Into this difficult situation stepped another notable woman, Marjorie Rankin Post. Born in New Jersey in 1895, she moved with her family to the Massapequas in the early 20th century. Her father was appointed postmaster and she succeeded him in 1922, becoming Massapequa’s first female postmistress. She subsequently became involved in operating an insurance company, and worked as an ambulance driver in World War II, ferrying wounded soldiers from the Brooklyn Navy Yard to Mitchel Field for treatment. She later became active in local politics and was appointed to a vacant seat on the Town of Oyster Bay’s Council in 1957, and became its first councilwoman. Post knew Louise from her activities in the Massapequas, and sided with her in her wish to change Little Unqua into a park. Her lobbying paid off after Louise’s death in 1961, because Oyster Bay’s Town Council voted to purchase the 42-acre property for $893,000. Subsequent votes approved spending $2.5 million to tear down Little Unqua and construct a park based on the recently-completed Plainview-Bethpage Community Park: three swimming pools, handball and tennis courts, picnic grounds, playgrounds and ample parking.

Upon its completion in 1965, the park was named for Marjorie Post, despite her objections. It seems a worthy memorial to a woman whose efforts have had a positive and continuing impact on her community.

George Kirchmann is a trustee of the Historical Society of the Massapequas. His email address is gvkirch@optonline.net.