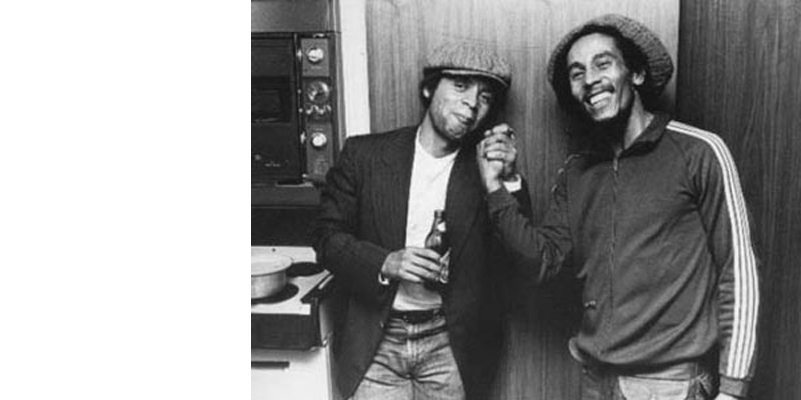

(Photo by Danny Clinch)

Mayor David Dinkins once referred to New York City and its various ethnicities as being a gorgeous mosaic. It’s a term that can be unerringly applied to singer-songwriter Garland Jeffreys and the modest but no less impressive canon that he’s recorded in the past four plus decades. It’s a description he readily embraces.

“I’m a rocker for sure, but I also have this other kind of jazz vocal style and it probably has something to do with my multiracial nature,” he says with a laugh. “It’s inherent in all my various styles. It’s like I want it all.”

Born in Brooklyn’s Sheepshead Bay 1944 to a teen mom of biracial descent, Jeffreys was exposed to the music of Duke Ellington and Count Basie, with doo-wop, R&B and early rock and roll eventually shaping his tastes. And while most casual music fans might scratch their heads with unfamiliarity regarding his recorded work, save for a flirtation with mainstream success via heavy early ’80s airplay of his riff-heavy cover of the ? and the Mysterians smash “96 Tears,” Jeffreys is part of a class of urban singer-songwriters whose heyday fell between 1977 and 1982. During this era that spanned the CBGBs explosion and the advent of MTV, a coterie of artists that included Graham Parker, Ian Hunter, David Johansen, Elliott Murphy, Lou Reed and Rockpile’s Nick Lowe and Dave Edmunds were pumping out guitar-driven gems that were embraced by both new wave and what would eventually become classic rock radio. But of all these performers, Jeffreys drew from a larger palette of influences that included heavy doses of reggae.

“I discovered reggae in the late 1960s from a guy that used to give out towels in the YMCA, which was then on 23rd Street. I’d go to the gym almost every day and I heard this guy playing some music out of a small box and I asked him what it was. He said it was the Heptones,” Jeffreys recalled. “He turned me onto a couple of artists. I found it perfect for me in terms of my songwriting. It was simple enough. I realized that this was really perfect for me or at least I thought it was. So I started writing songs around it and I realized that this was music that I was beginning to love.”

It’s all part of a global outlook he adopted dating back to his time matriculating as an art history major at Syracuse University in the early 1960s, where he became friends with fellow musicians Reed and Felix Cavaliere. That academic experience, coupled with a 1963 stint living overseas in Italy as a student, broadened his appreciation for different cultures significantly.

“When I went to Italy, suddenly I’m living in Florence. I was just 19,” he explained. “It was just remarkable how I’d walk down the street and see Dentenudo Cellinni’s Perseus, facsimiles of David in different places that were identical; terra cotta sculpture in the street, the architecture and museums like the Ufizzi Gallery and those great, great places. For a guy from Brooklyn, there’s nothing remotely close to this in America.”

Fast forward to 1977, and Jeffreys has gone from being the frontman for Grinder’s Switch, a late ’60s outfit heavily influenced by The Band, to cutting a one-off Atlantic Records debut co-helmed by jazz producer Michael Cuscuna. Recorded with an impressive assemblage of seasoned sidemen, (see sidebar), this would become a habit the undefinable artist embraced going forward. Starting with his 1977’s Ghost Writer, the first of three A&M Records releases, Jeffreys became known for urban narratives that often touched on issues of race in the big city. His old muse reggae was used to great effectiveness on numbers like the title track and “I May Not Be Your Kind” and would later pop up on a cover of newfound friend Bob Marley’s “No Woman No Cry” as well as more recently on 2011’s “Roller Coaster Town.”

Following 1983’s Guts for Love, Jeffreys would only return to the recording studio two times until 2011. In 1991, he tied his fortunes to RCA Records for the classically underrated Don’t Call Me Buckwheat, a collection of songs that used doo-wop, rock, reggae to address racial issues the way Marvin Gaye used What’s Going On to touch on civil rights and the environment. The import-only 1997 follow-up Wildlife Dictionary addressed relations between the sexes and preceded a hiatus where the newly minted parent embraced being a father to daughter Savannah.

“I was a father late in life and knew I didn’t want to be an absentee father in the sense of being on the road or traveling,” he said shaking his head. “I just didn’t want to do that, at least in the first five or six years.”

Fast forward to 2015 and the only child of Garland and Claire Jeffreys is a well-adjusted student thriving at Wesleyan University. With her old enough to be popping up on stage with dad in recent years, her pop has ramped up his recording efforts, releasing The King of In Between in 2011 and its 2013 follow-up Truth Serum . The work of a man who was obviously stopping to take stock of his life, it’s been a triumphant return for Garland Jeffreys that’s led to a whirlwind of touring that will take him to the West Coast, the South, Europe and a first-ever jaunt over to Australia. And as busy as he is recording a yet untitled project, for Jeffreys, it’s good to be back.

“[Recording my latest albums] has been a dream experience,” he admitted with a broad grin. “They rank up there with the Ghost Writer experience, because it was so easy in the end because everything had been prepared. It’s been a while since I made real records for worldwide release and now I’m working on songs for another one.”

Garland Jeffreys will be appearing on July 25 at Glen Cove’s Page One Restaurant. For more information, please call 516-676-2800 or visit www.myfathersplace.com. Jeffreys will also be appearing on Aug. 6 at Amagansett’s Stephen Talkhouse. For more information, call 631-267-3117. or visit www.stephentalkhouse.com.