In one week in September, soon after we commemorated the 14th anniversary of the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attack on our country, there were three widely publicized stories that revealed the ugliness of post-9/11 America.

At a town hall meeting in New Hampshire, Republican campaign front-runner Donald Trump was questioned by a man who said, “We’ve got a problem in this country; it’s called Muslims. You know our current president is one. You know he’s not even an American.” Obviously, the questioner felt comfortable asking this question of Mr. Trump, whose rhetoric about immigrants has been, to put it mildly, less than kind.

(Photo courtesy of Ali Goldstein/NBC)

Mr. Trump tried to laugh it off. But instead of correcting the audience member’s false assertion about President Obama or challenging his bigoted smear of Muslims, he just let it stand.

Shortly thereafter, Dr. Ben Carson, running close behind Mr. Trump in the campaign, asserted on Meet the Press that he would not be comfortable with a Muslim as President of the United States.

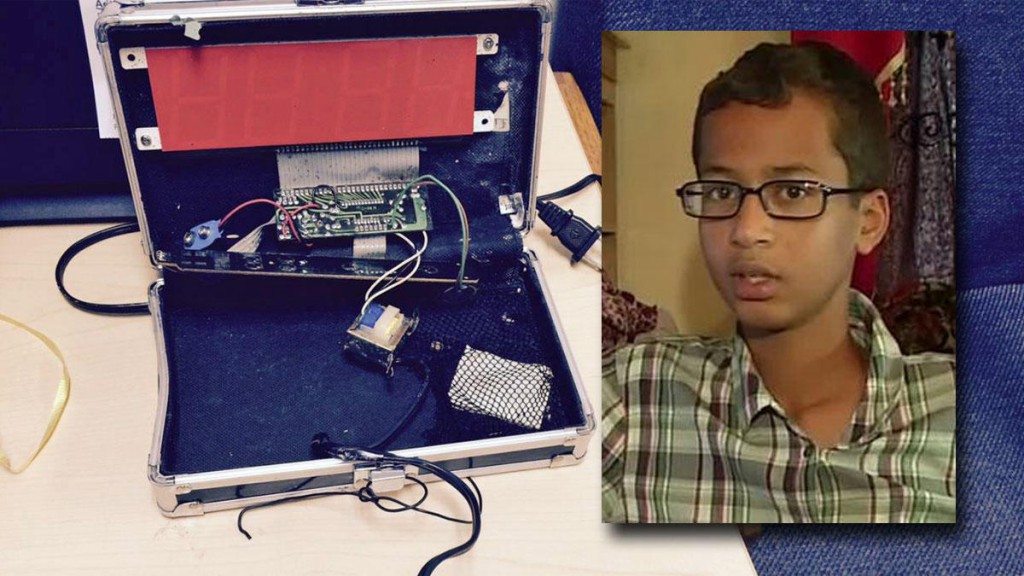

Just prior to these ugly interchanges, Ahmed Mohamed, a Muslim boy living in Irving, TX, was arrested for bringing a homemade clock to school. A teacher who thought it was a bomb reported Ahmed, a ninth grader, to the police, who then arrested him.

President Obama invited Ahmed to the White House, telling him, “Cool clock, Ahmed. Want to bring it to the White House? We should inspire more kids like you to like science. It’s what makes America great.”

Although these stories were well-publicized, they represent only the tip of the iceberg in post-9/11 America. In recent years I had an encounter that is probably more typical than you’d expect.

During a roundtable group forum on immigration and youth held at North Shore Child & Family Guidance Center’s Roslyn Heights headquarters, a 12-year-old boy named Muhammad, who was listening intently to others tell personal stories about leaving their homelands and struggling to fit in after arriving in the U.S., decided to speak up.

With a trembling voice, Muhammad revealed that there were kids in school who taunted him. “They’ve been calling me ‘terrorist’ for years because of my name.” Muhammad is an Arabic name that means praiseworthy. But, instead of feeling proud, Muhammad felt like an outcast.

Muhammad sat slumped in his chair and spoke softly and guardedly, but clearly and eloquently, and he was heard. By the end of the day he had received so much support from the group for having the courage to speak out that he was beaming.

Muhammad sat slumped in his chair and spoke softly and guardedly, but clearly and eloquently, and he was heard. By the end of the day he had received so much support from the group for having the courage to speak out that he was beaming.

During the lunch break I approached him to ask him how he was doing. He said, “Everybody is telling me that I talk good. I didn’t know that I could talk so good. Nobody ever told me that before.” Muhammad left the meeting feeling praiseworthy, a feeling befitting his name—a name he was given at birth that he should feel proud to have.

Sadly, stories of racism and hatred against Muslims are not rare—not surprising given the recent example of Ahmed Mohamed’s arrest for his innocent work on a school project. I recall that shortly after 9/11 one Muslim mother who came to us for help revealed that she dyed her children’s hair to a lighter color so that they wouldn’t be viewed as “kin of terrorists.” Those are the lengths that one mother felt were necessary to protect her children and they display a sad commentary on our culture.

As we remember the thousands who were lost on 9/11, along with other acts of terrorism, we should not lose sight of the fact that profiling people of Middle Eastern descent as terrorists or as sympathetic to terrorists must be confronted. Such widespread profiling is detrimental and devastating to thousands of innocent children and their families, many of whom were not even born until after Sept. 11, 2001. It’s time to let our voices be heard and, unlike Mr. Trump, take a stand against bias when we hear it.

Andrew Malekoff is the executive director of North Shore Child & Family Guidance Center, which provides comprehensive mental health services for children from birth through 24 and their families. To find out more, visit www.northshorechildguidance.org.