Many people hope to leave their mark on the world, but most people’s legacy is not as permanent as a tattoo

Irving Roth’s legacy has been tattooed on others…literally.

It began several months ago when Roth was scheduled to speak for Christians United for Israel (CUFI) in Phoenix. CUFI Western Regional Coordinator Randy Neal greeted Roth at the airport to drive him to his hotel. It seemed like any other trip for Roth.

Born on Sept. 2, 1929, in Kosice, Czechoslovakia, Roth lived a happy childhood, going to school, playing with friends, enjoying soccer. As Hitler rose to power and World War II broke out, Roth’s life changed dramatically. His family moved to Hungary, but the situation only worsened. While Roth survived Auschwitz and Buchenwald, he lost his brother, grandparents and other relatives.

After the liberation, Roth returned to his hometown in Czechoslovakia and found his parents, who survived being hidden by righteous gentiles, waiting for him. In 1947, Roth and his parents moved to Brooklyn, where Roth completed high school and eventually earned a degree in electrical engineering.

Since retiring, Roth travels every two or three weeks to speak about his experience in the Holocaust and teach others the lessons of history. CUFI is an organization for which Roth speaks often, and after staffing an organized group trip to Poland together in 2009, Roth and the Christian leader Neal had become close friends. Neal was so moved by Roth’s story and the way he conveyed it that he asked Roth to speak at CUFI events. And so, after six years of partnering with CUFI, Roth had no reason to

Since retiring, Roth travels every two or three weeks to speak about his experience in the Holocaust and teach others the lessons of history. CUFI is an organization for which Roth speaks often, and after staffing an organized group trip to Poland together in 2009, Roth and the Christian leader Neal had become close friends. Neal was so moved by Roth’s story and the way he conveyed it that he asked Roth to speak at CUFI events. And so, after six years of partnering with CUFI, Roth had no reason to

think this day in Phoenix would have been unlike any other, until Neal asked him a question that

he had never expected to hear.

“We were in the car coming from the airport and going to the hotel, and he said to me, ‘Irving, I have a question. I would like to have your number tattooed on my arm. Exactly the same number. Exactly the same place. Would you object?’” Roth recalls. “That afternoon, we went to a tattoo parlor.”

While this may seem impulsive, it’s the farthest thing from it.

While this may seem impulsive, it’s the farthest thing from it.

“This is done with great reverence, not something to take lightly,” Neal explains over the phone, emotion rising in his voice. “His story would not be forgotten on my watch.” Neal has thus become the “surrogate survivor” of Roth, the A-10491 tattoo serving as a physical manifestation of the immense impact Roth has had on this man’s life.

Roth began a program called Adopt a Survivor in 1998, after participating in March of the Living with high school students. Through the Adopt a Survivor program, students are partnered with Holocaust survivors whose stories they learn and can carry on after the survivor passes away. This program was inspired by the idea that understanding a person’s experience in the Holocaust is more than facts and figures.

Returning to Auschwitz in 1998 with the March of the Living trip, Roth realized that he didn’t want the students to think of his grandfather as an “image of a corpse turning green from Zyclone B gas” but as a human being, devoted to his family, his faith and his morals. By adopting a survivor, younger people can become what Roth calls “surrogate survivors” so that the stories can live on even when the survivors don’t. In this sense, Neal really is a surrogate survivor.

“It was a very moving experience,” Neal says. It even brought the tattoo artist to tears, evoking memories of his own grandfather’s tales from World War II.

A few months after this incredible day in Phoenix, Roth was sitting in his office at Temple Judea of Manhasset when he received a call from Neal. He was in Portland on a CUFI tour of the northwest and on the phone with him were Pastor Aaron Taylor and a former radicalized Muslim, who wished to remain unnamed. They’d seen Neal’s tattoo and wanted Roth’s permission and blessing to do the same. Roth approved.

“There are four people in this world who have this number,” Roth says. One Jewish Holocaust survivor, two Christians and a former radicalized Muslim.

“There are four people in this world who have this number,” Roth says. One Jewish Holocaust survivor, two Christians and a former radicalized Muslim.

“We’re doing this for the day when our grandkids ask, ‘What does that mean?,’” Neal says. “We’re not trying to start a trend; there is a deep sense of commitment. If there is ever a day when bad people want to know where we stand with the Jewish people, we just wear a T-shirt.”

Neal explains that these three men aren’t trying to spread a fad; these tattoos hold great significance for them and they don’t want to belittle it by drawing attention to it. Yet the story is so inspirational and compelling that it may very well take on a life of its own, and others may soon follow suit.

Still, Roth’s legacy transcends far beyond these physical manifestations to all of the minds he reaches through his professional speaking and work at the Holocaust Center of Temple Judea of Manhasset.

When Roth arrived in the United States in 1947, he was ready to speak about his experience in the Holocaust, but he found that people weren’t interested in listening. His uncle, who Roth remembers fondly as a wonderful man, had been living in Brooklyn during the war and held a stubborn stance, often saying, “What happened in Europe was evil. Let it sink into the Atlantic Ocean. This is a new life.”

Even at Midwood, where Roth attended high school in Brooklyn, when the student newspaper featured him, the editor focused mainly on the sheepskin coat that Roth was forbidden to wear after a 1939 law in Czechoslovakia prohibited Jews from wearing luxury items rather than on the experiences of the Holocaust.

“What’s very fascinating is what stuck in the editor’s mind, the fact that I had to give up my sheepskin jacket because I was a Jew,” Roth says. “Because the idea that six million Jews were murdered didn’t really penetrate. He couldn’t relate to it.”

When his two sons were growing up, they began asking their father questions, wondering why he had a number tattooed on his arm. Little by little, Roth recounted the story to his children—the memories of his childhood, getting kicked out of school for being a Jew, his father losing his business, the concentration camps and losing his brother. With four grandchildren and a great-grandchild, Roth continues to share his story with them.

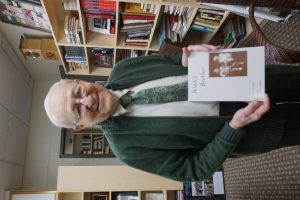

It wasn’t until Roth retired from a 40-year engineering career that he began professionally speaking about his story. Now, Roth speaks to thousands of people each year, with audiences ranging from children to adults and includes Jews as well as people who had never even heard of the word Holocaust. He wrote his memoir, Bondi’s Brother, helped edit Adopt a Survivor: An Antidote to Holocaust Amnesia and is currently working on a third book about an alternative approach to teaching Torah that better relates to youth.

It wasn’t until Roth retired from a 40-year engineering career that he began professionally speaking about his story. Now, Roth speaks to thousands of people each year, with audiences ranging from children to adults and includes Jews as well as people who had never even heard of the word Holocaust. He wrote his memoir, Bondi’s Brother, helped edit Adopt a Survivor: An Antidote to Holocaust Amnesia and is currently working on a third book about an alternative approach to teaching Torah that better relates to youth.

Executive Director of the Holocaust Center at Temple Judea of Manhasset since 1998, Roth has brought survivors, speakers, concerts and artwork to the Holocaust center, which is the only one of its kind built by a single synagogue in the United States. Roth has received numerous awards including the Spirit of Anne Frank Outstanding Citizen Award, as well as city keys to Lake Charles, LA, and Findlay, OH.

When Roth speaks about the Holocaust, he doesn’t simply share his story; he works to relate the events of 70 years ago to today’s world, “so that the Holocaust becomes not an abstraction but an event that happened to a real person to whom they can relate,” he says. “And people haven’t changed really. Jealousy, love, hatred, relationships still exist. Technology has changed, but we as humans…not really.”