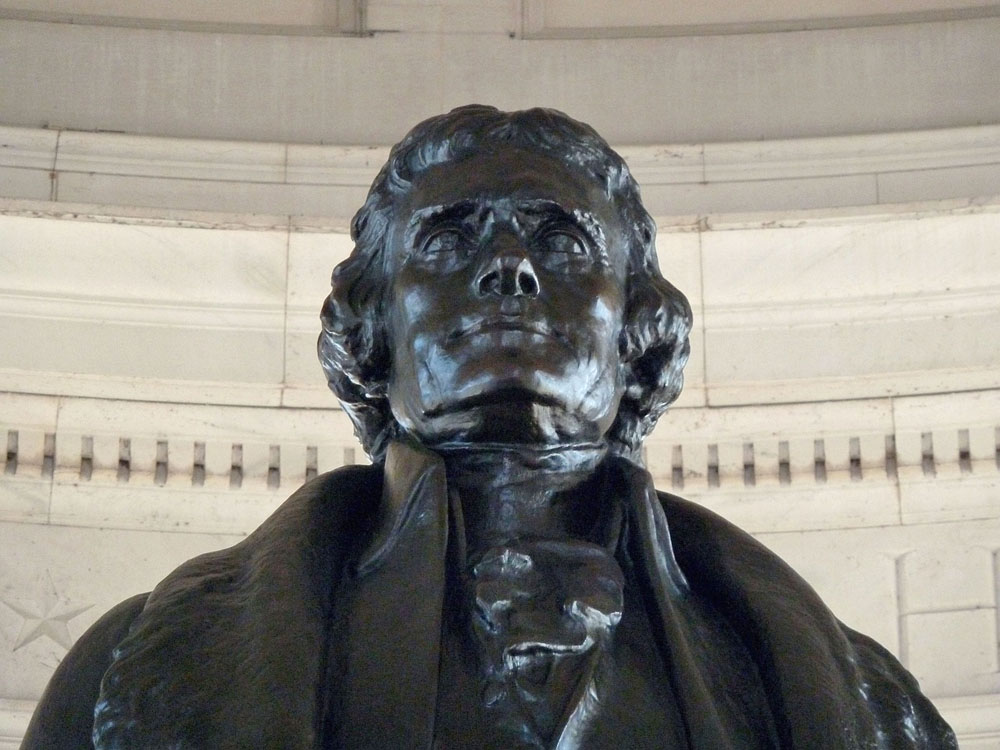

Debates over statues of historical figures are once again in the news. This time students at Hofstra University are at odds over the presence of a statue of Thomas Jefferson in the university’s student center.

Those supporting the removal of the Jefferson statue argue that it is unacceptable for the university to celebrate a figure who held slaves and who regarded African Americans as intellectually inferior to whites. To gain support for their position, they have launched an online petition calling for the statue’s banishment from campus.

Others insist that, his blind spots on race notwithstanding, Jefferson is too important to the fabric of America to have his statue cast aside. Pointing to his support for the abolition of slavery, they’ve started their own petition, one calling for the university to keep the statue on campus.

Who can dispute Jefferson’s place in our history? No matter where one stands politically, it’s inconceivable to think that someone who played such an integral role in the creation of the American landscape could—or should—be deleted from memory.

But there’s a difference between recognizing an individual’s importance and turning him or her into an icon of unqualified veneration. At the height of the Christopher Columbus statue controversy last year, many defenders of the man “who sailed the ocean blue” naively insisted that Columbus’s story requires no scrutiny or reassessment.

In fact, it does—as does Jefferson’s. Like so many who have shaped America, both reflect the prejudices of their times.

But rather than simply kick statues of Jefferson, Columbus and other “flawed” figures to the curb, schools and municipalities would be wise to contextualize their subjects’ lives, acknowledging their contributions, highlighting their complexities and contradictions, and providing unsanitized history lessons in the process.

Such an approach has been taken elsewhere.

The city of Richmond, Virginia, for example, has not removed statues of Confederate generals (an indisputable part of that city’s history) but instead erected more statues, including one of Abraham Lincoln, another of the African American students whose demands for a better education gave traction to the Brown v. Board of Education case, and—maybe most important of all—a 15-foot bronze sculpture of two enslaved African Americans embracing near the site of Richmond’s former slave market.

In Boston, the city’s Irish Famine Memorial details the experience of those who fled Ireland’s potato famine in the 19th century only to encounter deprivation and prejudice in America. Though the immigrants’ story, presented in a series of panels, includes text noting Boston’s initial neglect of this vulnerable population, many in the city have praised the memorial for its unflinching honesty.

Could Hofstra—or any other college or community—provide a balanced account of Jefferson’s life, including his contributions and shortcomings, alongside his likeness? Could the treatment acknowledge different points of view about Jefferson’s words and actions?

I would hope so. Imagine a statue of Jefferson accompanied by some straightforward text about his life and times. Viewers could learn, for example, about his vision for America, epitomized by his contributions to the Declaration of Independence and his still influential Notes on the State of Virginia.

They also could learn about his devotion to learning, a commitment reflected in his founding of the University of Virginia, one of the country’s premier universities.

But viewers of Jefferson’s statue should not be spared his less admirable traits—his denigration of the character of African Americans (whom he likened to simple and happy children) and his unwillingness to free his slaves—all, ironically, while advocating the abolition of slavery.

Such aspects of Jefferson’s life shouldn’t be glossed over in the interest of sentimentality.

Like everyone else who contributed to the making of America (including others whose statutes are now threatened with removal), Jefferson matters. He deserves his place in history, perhaps even on our campuses or our town squares.

But the least educators and elected officials can do is tell the truth about him, including the shameful aspects. We’re past clichés and half-truths. And silence just isn’t an option.

—Richard Conway

Richard Conway is the faculty adviser of The Vignette, Nassau Community College’s student newspaper.