Most Long Islanders have never visited the Hofstra University campus. Only a modest percentage of parents send their children to college there. Hofstra has been in the news lately, not for academic achievement by its faculty members or students, but over its Thomas Jefferson statue.

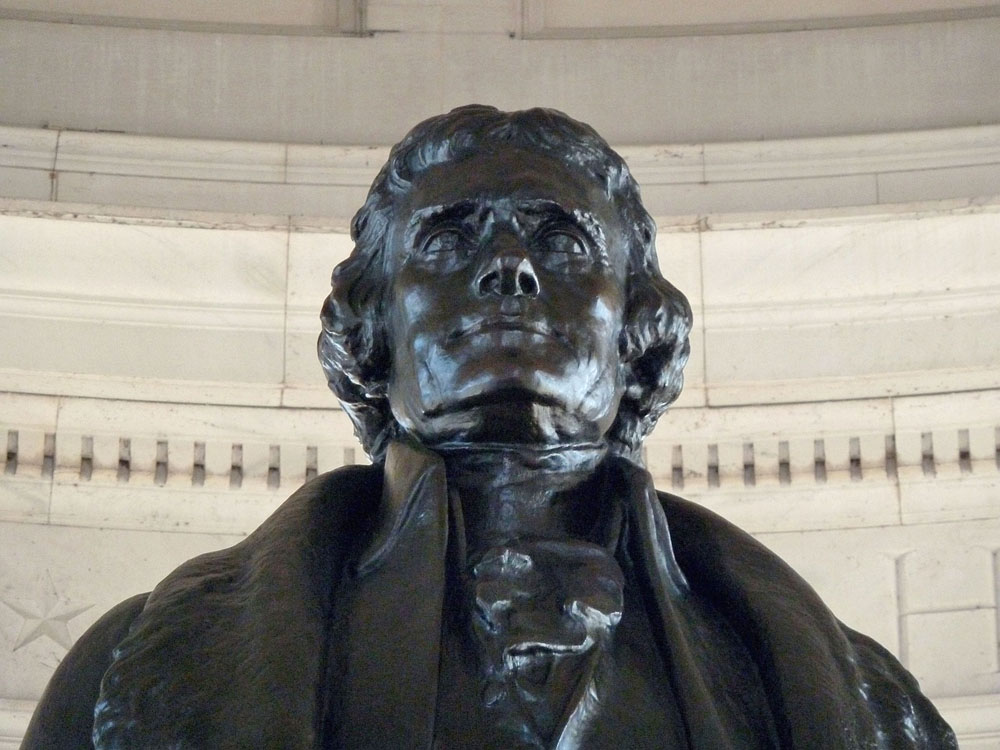

Why would anyone erect a statue to Thomas Jefferson? There was a time when millions of New Yorkers, living in a multi-faith metropolis, placed great value in their ability to practice religious freedom. And who, may we ask, is the founder of religious freedom in the United States? In the 1920s, Gov. Al Smith, the first Roman Catholic to win a presidential nomination, declared a “Thomas Jefferson Week” in the New York City public school system. Another New York icon, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, spoke glowingly of Jefferson at the 1943 dedication to the famous memorial to the man in Washington, DC, all at a time when the very idea of religious freedom in an age of Hitler and Stalin was in danger of being stuffed out.

All of this was decades, if not a century, ago. The rising generation, at least according to surveys, is heavily irreligious, if not atheistic. Freedom of religion may not matter, because religion itself may not matter. For his detractors, Jefferson’s slave-owning past supersedes everything else the man did. Americans have forgotten the Revolutionary War. What if the colonials had lost? Well, the young Thomas Jefferson, not to mention Washington, Adams and Franklin, et. all, would have found themselves hanging from an oak tree. This, too, once mattered greatly to Americans. Meanwhile, today’s Democratic Party has done away with its Jefferson-Jackson Day dinners.

Hofstra advertises itself as an institution of higher learning. Concerning Thomas Jefferson, all roads lead to Dumas Malone’s Pulitzer Prize-winning multi-volume history of the man. Here is Jefferson as a man in full: What shaped his thinking, what drove him to action, plus his transformation from a polemicist to statesman to chief executive, to, finally, father of the Virginia dynasty in early American politics.

Is there is anyone at Hofstra’s History Department who has at least dipped into some of Malone’s magnum opus (we’ve only read two volumes ourselves)? To administrators, faculty members and students alike, we say enough is enough: If you’ve read Malone and still dislike Jefferson, we can agree to disagree. If you haven’t read at least a portion of Jefferson’s major biographer, then you have forfeited your right to form an opinion on Thomas Jefferson.