ZZ Top frontman rocks with guitar-driven solo album

Blues may have its roots deep in the last century, but if there’s anyone qualified to drag it kicking and screaming into the current millennium, it’s Billy Gibbons. While most music fans know the ZZ Top founding member for his hirsute appearance and the string of videos his band had in heavy rotation on MTV during its heyday, the man has first and foremost been a fierce advocate for the aforementioned genre. As someone who has worshipped at the musical shrines of Jimmy Reed, Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf, Gibbons walks the walk, no more so than on his second solo outing, the recently released The Big Bad Blues. What started out as a group of friends knocking around in a studio in the Houston native’s hometown turned into an 11-song platter dedicated to a number of his musical heroes along with a spate of originals.

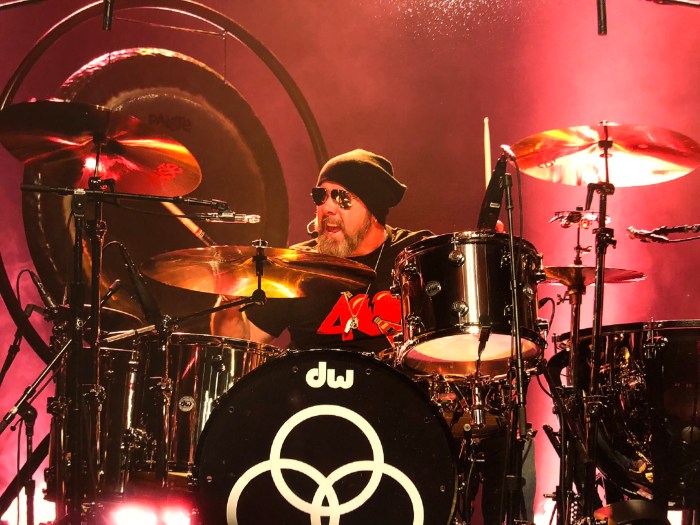

“I had booked some sessions at our studio down in Texas known as Foam Box Recordings. And our two engineers, Mr. Joe Hardy and G.L. ‘G-Mane’ Moon, were all set up and ready to rock. Coincidentally, Greg Morrow, our fearless drummer from way back, was passing through town. So Hardy grabbed a bass guitar, and I grabbed a six-string, and Mr. Morrow stepped in,” Gibbons explained. “Of course, wanting to be the continual interpreters playing this thing we call blues, we started off with the usual run-down of our favorites—Jimmy Reed, Howlin’ Wolf and of course, Muddy Waters and Bo Diddley in the mix. After a couple of days, we were having such a good time that Mr. Hardy asked if I wanted him to play back what we had been doing. I asked him what he was talking about, and he said he’d had the tape machine running. We were rather satisfied with what we started, and who should show up but James Harmon, a famous harmonica player from California way. He added his little spice to the mix and off and running we go. That stimulated me to pick up pencil and paper and try my hand at writing some blues-inspired numbers. I think it’s going to work out nicely, and at the present time, I’m satisfied.”

Anyone familiar with Gibbons’ raspy growl and equally greasy-sounding riffing will find plenty to sup on here.

Gibbons originals like “That What She Said,” a slow-rolling number punctuated by Harmon’s harp fills and the composer’s fretting and the snappier shuffle “Hollywood 151” fit in well alongside the album’s handful of covers. Highlights include the Waters warhorse “Rollin’ And Tumblin’” turned into a percolating stomper and two Diddley nuggets—the straightforward strut “Bring It To Jerome” and “Crackin’ Up,” a quirky number reminiscent of Mickey and Sylvia’s 1956 hit “Love Is Strange.” Dipping into the canon of the man born Ellas McDaniel was an opportunity Gibbons couldn’t resist.

“I’ve always been fascinated by the early work from Bo Diddley. Initially, his studio work was the original trio, which was Bo on guitar, Clifton James on drums and of course, Jerome Green on maracas, and that was it. There was no bass guitar and the sound was—you’re not missing anything. Those were always fascinating,” Gibbons said. “Of course, the other track, ‘Crackin’ Up,’ has been covered a number of times. But it’s that wacky, inside-out, upside down guitar figure that starts the song off. I’ve marveled at that short stab at an intro. Keith Richards and I were speaking about this at length, and he agreed that one introduction was mystifying. We were determined to make it work. It took over a week to try and iron it out, but we feel a great sense of accomplishment. This was something that I never felt would be repeated. Long story short, we’re happy with all of it.”

On the road, Gibbons promises that fans will be getting quite a dose of the blues, including a number of more obscure gems that the sexagenarian rocker plans to dust off for the masses.

“We’re going to stir it up. What did not make the record was a handful of other blues covers that deserve some light of the day. I’ve got to hand it to everybody that showed up at the studio. What was impressive was that everything was steered towards some obscure numbers that are rarely heard, which intrigued all of us that were in the studio,” he said.

“Having tiptoed through the deep cuts, I thought, ‘Gee whiz, it’s one thing to present your best shot at emulating what the originators invented from the way-back. But why not highlight some of the interesting tracks that rarely get heard?’ Unless you’re an aficionado that spends 24-7 digging deep, there’s a lot of good stuff that’s waiting to be unveiled. So that’s our plan.”

As someone whose mother got the ball rolling by bringing Gibbons and his sister to an Elvis Presley concert when the future Rock and Roll Hall of Famer was five years old (“I thought, ‘I like that.’ Who didn’t? Everybody was liking that.”), the pursuit of getting his own guitar came to fruition nine days after his 13th birthday, when his father gifted Gibbons with an electric guitar and an amp.

“From the time I saw Elvis and B.B. King, I don’t think there was a day that went by when I didn’t badger my folks about a set of drums or a guitar. Sure enough, on Christmas Day, my dad unveiled a guitar. Then he pulled out a little Fender amplifier. It was this tiny, radio-looking thing,” he recalled. “So my sister and I raced back into my room and she started saying, ‘Let’s hear it, let’s hear it.’ I think the first lick that I had tackled was the introduction to Ray Charles, ‘What’d I Say’ and before the lights went out, I had the Jimmy Reed figure. We called it the ‘dunta, dunta.’ She said, ‘Play that dunta-dunta.’”

What followed has been quite the musical journey driven by his time in ZZ Top. Among his most memorable experiences was not only opening for Jimi Hendrix as a member of his pre-Top band The Moving Sidewalks, but having the audacity to include “Foxy Lady” and “Purple Haze” in the set. (“I kind of glanced over at the shadows, and he was standing at the side of the stage and he had his arms folded. When we made our escape, he grabbed me and he said, ‘I like you. You’ve got a lot of nerve.’”) More recently, it was touring with John Fogerty and collaborating with the Creedence Clearwater Revival founding member on a new song called “Holy Grail.” (“We wrote a song together and we just had a great time. Once it was buttoned up, he said, ‘You know we’re going to have to play this together.’ I said, ‘That’s fine by me.’”) A longtime collector of African art, Gibbons’ fascination can be traced to the respect he has for honoring musical and cultural tradition.

“Back to 1990, we started the sessions that wound up coming out as the release Rhythmeen. I bumped into an African art dealer and picked up a little statue,” he said. “He asked what I was going to do with it, and I said I was going to put it in the doorway of the recording studio in such a way that we have to turn sideways to enter the room. And in so doing, this would not be something on a shelf. It would actually be functionary. It will remind us of what we’re supposed to do—go back to the roots.”