Just a week after the “What’s In My Water?” report came out from New York Public Research Group (NYPIRG), the Port Washington Water District (PWWD) held a community informational presentation, followed by a question and answer session on June 5.

The “What’s In My Water” report compiled data from multiple government records sources about local public groundwater from 2013 to 2016.

The report identified potential threats to drinking water quality given their location and nature for the area, including Chez Valet Cleaners (state superfund site: an inactive hazardous waste disposal site that poses a significant threat to public health or the environment), the former Thypin Steel Plant (brownfields: a property with the presence or potential presence of a hazardous substance, pollutant or contaminant), Plaza Cleaners (state superfund), the former Munsey Cleaners (state superfund) and the Port Washington Landfill (state superfund and federal superfund: an area that has been contaminated with hazardous material deemed eligible for cleanup by the EPA due to the harmful effects these chemicals can have on human health) on West Shore Road.

The regulated contaminant violations list included about 20 different contaminants—including 1,1-Dichloroethylene, Bromomethane, Carbon tetrachloride, Coliform (TCR)—with 124 violations, with most being monitoring and reporting violations and one maximum contaminant level violation. The report has 453 samples of unregulated contaminants, including 1,4-dioxane, chlorate, strontium, vanadium and 1,2,3-trichloropropane.

However, this data was tested on groundwater, which is raw, untreated water that exists within Long Island’s aquifer system, not drinking water, which is groundwater treated to meet local, state and federal guidelines and is then pumped into the distribution system and into customer homes.

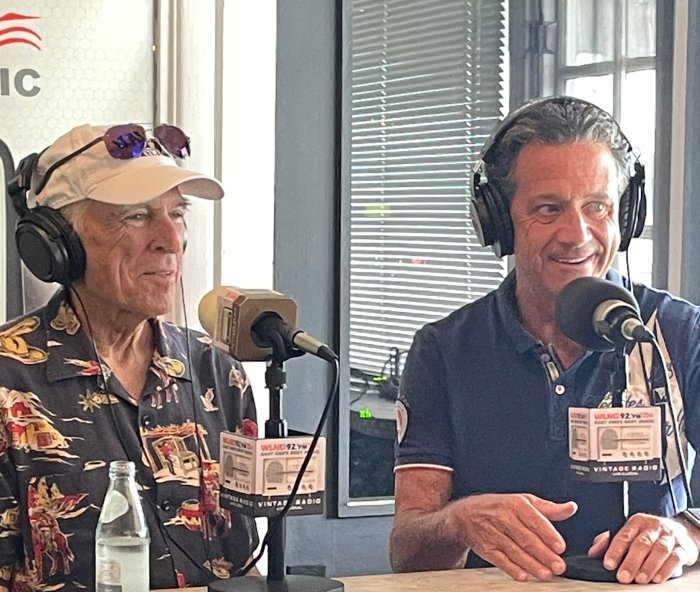

Superintendent Paul Granger explained to the community how the treatment process works to turn the groundwater into drinking water.

“What we have on Long Island is an EPA designated sole source aquifer that serves Nassau and Suffolk counties,” said Granger. “Three million people live on our aquifer. We work, we live, we play. We did a lot of manufacturing, so unfortunately, whatever you do on top makes its way into the ground. You drill a well into the aquifer, you put a pump in the well. Pumps we maintain put out 1 to 2 million gallons per day. We use electric motors to draw the water out and it goes into another facility, where we test the water, treat the water in order to meet all state, local and federal regulations. It is a very intensive, expensive process.”

Once the water is treated, it is further tested to make sure the treatment works and then goes into either the distribution system to homes or becomes stored in storage tanks.

“The quality of Long Island’s drinking water has been a prominent topic of conversation recently,” said PWWD Commissioner David Brackett, who has been a Port resident for 57 years. “While it is true that our sole source aquifer faces significant challenges, the Port Washington Water District has remained vigilant, remaining ahead of the curve to ensure the quality of our community’s drinking water.”

The three PWWD commissioners, Brackett, Mindy Germain and Peter Meyer, along with Granger, explained the Port community faces many water challenges, including increasing demands for water and its relationship with the salt/fresh water barrier, increasing presence of regulated and unregulated contaminants in the groundwater and the cost and timeline for infrastructure upgrades.

In order to combat saltwater intrusion, the district representatives explained the only measure to protect at-risk wells is reducing the amount of water pumped, meaning water conservation is the answer. The district has a plan, which includes the Be Smart and Green, Save 15 campaign, among other conservation efforts, to reduce peak season water quantity demand by 15 percent by 2020-21. The district also utilizes distribution system modeling, which allows the district to analyze pressures and flows through the district for uses like optimizing system controls (tank level, pump on or off), analyzing fire flows for new developments of ISO requirements and determining water age.

The district’s annual 2018 Water Quality Report shows that the district is not in violation regarding any regulated contaminants tested in the treated, drinking water. These tested contaminants include microbiological (coliform), inorganic (arsenic, chloride), nitrates, radioactive (uranium), lead, copper and more.

Regarding volatile organic compounds (VOC), like gasoline, diesel fuel or paints, the district currently utilizes air strippers and granulated activated carbon to remove VOCs.

“Three years ago, it was about 144 contaminants. Now, we have probably over 160. I predict this year we’ll probably exceed spending $160,000 for analytical tests,” said Granger.

He explained the plant operators are all certified by the health department and while the district tests the water, the water is also sent to a New York State EPA certified laboratory.

“The health department who is our partner, even though we test the water, you have the health department come in unannounced to check distribution systems or well sites,” Granger said.

The PWWD participates in the Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule 4 (UCMR4), a U.S. EPA water quality sampling program, which monitors unregulated, but emerging contaminants in drinking water.

“It keeps us proactive,” said Granger. “As science advances, we can detect different compounds research finds and detect them at very low levels. Remember, one part per trillion is one second in 32,000 years and one part per billion is one second in 32 years. A lot of these emerging compounds are synthetic in nature, can occur naturally and have demonstrated a potential effect on the environment and health.”

Perfluorinated compounds (PFAS) are no longer an issue for the community. 1,4-Dioxane, which comes from industrial spills and plumes, is on the list of contaminants the PWWD is testing for as part of the program.

“The problem with 1,4-Dioxane is that it’s very difficult to remove,” said Granger. “You cannot use your typical treatment methods of air stripping or carbon. The science is still under development. You have to use a treatment method called Advanced Oxidation, which uses UV light and some sort of oxidizer, which is highly technical in terms of how you break the contaminant down. There is currently one AOP system approved by the health department. But it is important we move judiciously, but in a methodical fashion because you don’t want to invest in that treatment, spending millions of dollars. We want to spend our money wisely. The board is moving at a good speed to commence the pilot studies to get the data, so we make wise investments. The health department will come out with the maximum contaminant level. The drinking water quality council recommended one part per billion with regard to 1,4-Dioxane.”

However, Granger said the district is not waiting on the issue; the district has been monitoring the data, so the district has made operational changes.

“We took the wells where we’ve seen 1,4-Dioxane at elevated levels, we’ve put them in a lag position or we’ve turned them off in some cases,” said Granger. “When peak pumping comes up, we may need to use additional water, but we’ve made operational changes where we keep the distributed water less than one part per billion.”

What did you think of this article? Share your thoughts with me by email at cclaus@antonmediagroup.com.