In times of loss, mourners often hear the same phrase of sentiment shared by those consoling them in their grief:

“I know what you’re going through.”

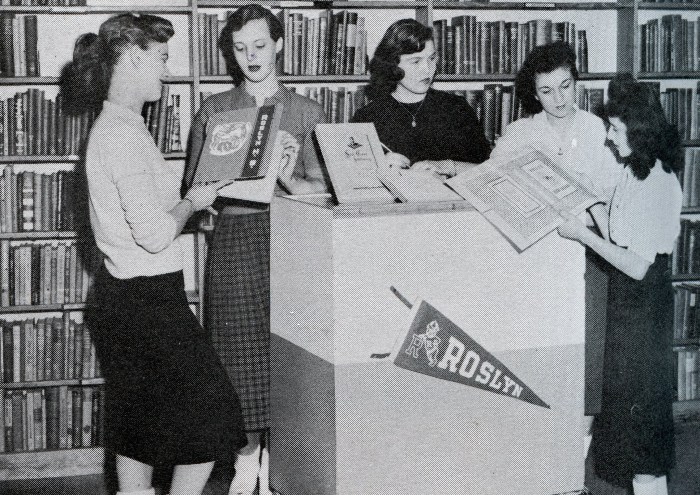

But for teenagers like Charlie Dubofsky and Sydney Hassenbein, both 16, the grief they experienced in the loss of their family members was something their peers overwhelmingly did not understand.

“They don’t know what it’s like,” Dubofsky said.

Within just three months of each other, the two teenagers experienced sudden and life-changing grief that most people so early in life don’t endure.

In February of 2023, Charlie Dubofsky’s dad, Ned Dubofsky, died. He was 54.

Three months later, Sydney Hassenbein’s younger brother, Drew Hassenbein, died when the car he was in was struck by an alleged drunk driver. He was 14.

But through their grief, the two girls came together and received the empathetic understanding they couldn’t necessarily receive from their peers.

“When I heard about Drew and the accident, I immediately reached out to her and so did my sister,” Dubofsky said. “We both just wanted to lend her an open ear and help her and be a support system for her.”

In their unification, the two girls had an idea: to establish a grief support group for other teenagers like themselves who are seeking understanding and support among their peers.

With an idea to bring to the community, the two girls reached out to the Sid Jacobson Jewish Community Center to partner on the support group.

In doing so they established The HERO Project, which stands for honoring their heroes, empathizing with others, remembering special times shared and living onward for their heroes.

“It’s almost like a big hug,” Dubofsky said about the HERO project gathering.

In partnership with the two teens are two licensed clinical social workers Amanda Foglietta and Taylor Graf.

Foglietta described her role in the HERO Project as supporting and guiding Dubofsky and Hassenbein, allowing the teens to take the reins in leading.

Dubofsky and Hassenbein lead every group meeting, preparing in advance a topic to discuss and a presentation to provide. Joining them as well are Foglietta and Graf.

Topics include talking about the meaning of grief, music and new beginnings.

Each meeting is an open and safe space for the teens, Hassenbein said, with an established protocol that everything discussed is confidential. The social workers are also present during the meetings for participants who may need additional support.

Teens coming to the meetings can bring friends, which Foglietta said helps them feel more comfortable in attending.

A typical meeting starts with attendees talking about how they feel at the moment, followed by a presentation on the prepared topic and group activities and discussions. At the end, Sydney Hassenbein said they will again ask how attendees are feeling after the meeting activities.

“It’s so nice to people who suffered something so tragic but look at how they’re moving forward,” Dubofsky said.

To aid participants who may not be comfortable sharing their thoughts out loud, the group offers an anonymous, online submission for them to write about how they feel.

And for those who aren’t comfortable talking at all, Dubofsky said they are welcome to just listen.

But each meeting looks a little different, and the girls have aspirations to continue diversifying their meetings with additions like meditations and guest speakers.

While the group helps teenagers working through grief, Charlie Dubofsky said it’s not always solemn.

“It’s just so nice to talk about a memory,” Dubofsky said. “It doesn’t always have to be so sad. You can laugh at something that’s funny or smile and reminisce on those happier times.”

In offering this support group, Hassenbein said it has helped their peers – and themselves – feel empowered.

“Talking about my dad, or just talking about grief and seeing how other people are struggling with that, it definitely shows how, one, you’re not alone – which is a big thing – and, two, I just think it’s like very nice to empathize with others,” Dubofsky said.

Not only does it help them and their peers process their grief, but it also helps keep their loved ones’ legacies alive.

“That was always something that my family said after the accident that all we can do now, all we have left is just to keep those memories alive, keep his legacy alive [and] just try to remember as much as possible,” Hassenbein said. “So talking about him during the group makes me feel good.”

Support groups like the HERO Project are rare, Foglietta said, praising the two girls for their impacts on the community with their support group.

“Some people have great support systems, some people don’t,” Foglietta said. “But being able to have someone who is going through it first-hand was very beneficial for them and that’s what they’re trying to do… They’re coming to the group and they’re leading with first-hand experience so they’re able to process what they’ve gone through and tap that knowledge onto other teens.”

Foglietta said that not working through grief has long-term effects on an individual, and especially affects children and teenagers whose brains are not fully developed.

“So not being able to have a safe place to process your grief is really detrimental later in life,” Foglietta said. “From that perspective, this group is making a huge impact.”

Hassenbein said reaching an underserved community was their purpose in establishing the HERO Project.

“There’s so many groups for adults but obviously your typical teenager you wouldn’t think would be experiencing this,” Hassenbein said. “That’s also why we came together because this is what the community is lacking.”

The word on the HERO Project has surpassed the Roslyn community, with participants traveling from as far as Huntington to attend. But the teens have even bigger aspirations, with goals to have their program help teens across the globe.