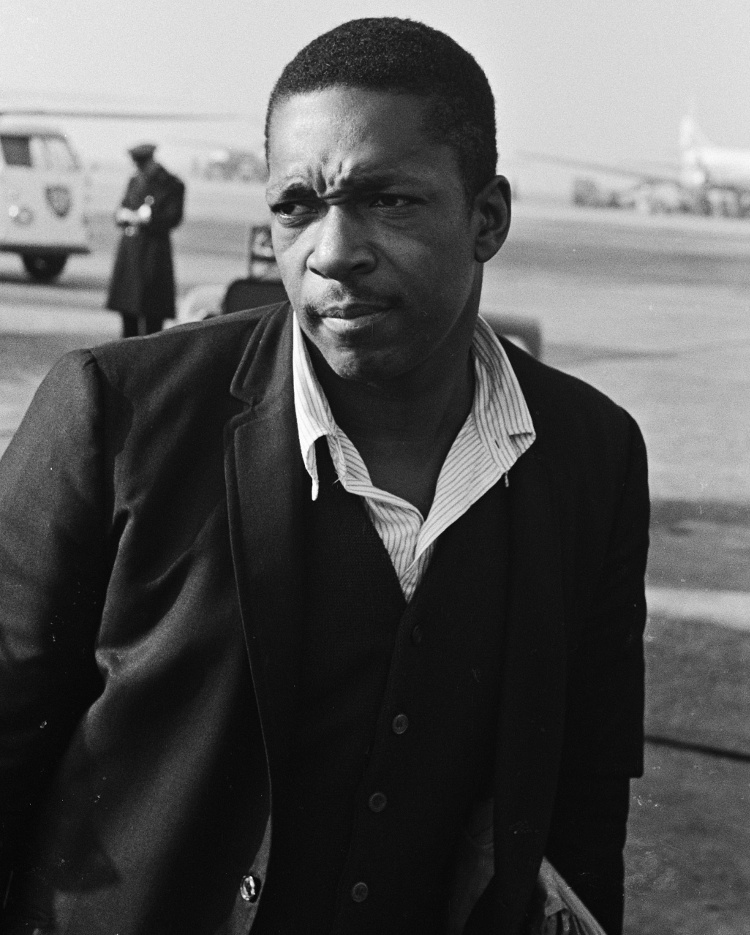

Like a truly innovative, modern jazz composition, the John Coltrane home in Dix Hills—where the greatest American saxophonist created A Love Supreme—is also a work in progress.

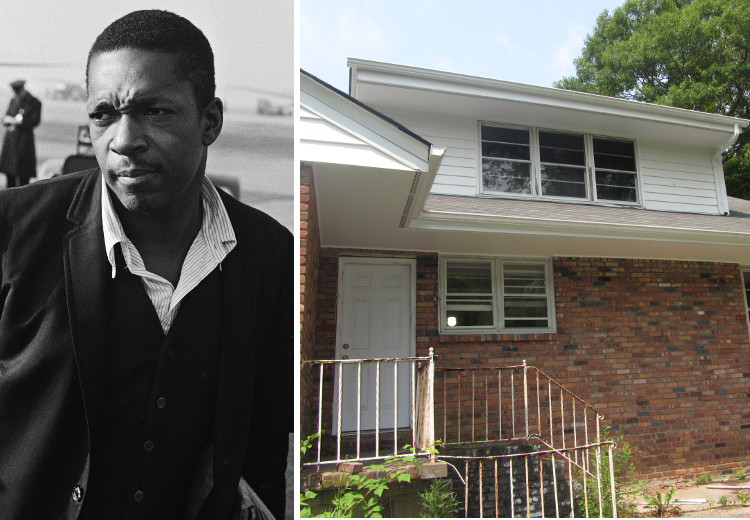

But ever since the National Trust for Historic Preservation named his modest 1952-ranch-style house to its 2011 list of America’s 11 Most Endangered Historic Places, progress has indeed been made. Today, the house now has a new roof, new siding and new soffits. Yet so much more remains to be done before his legacy can be rightfully preserved there.

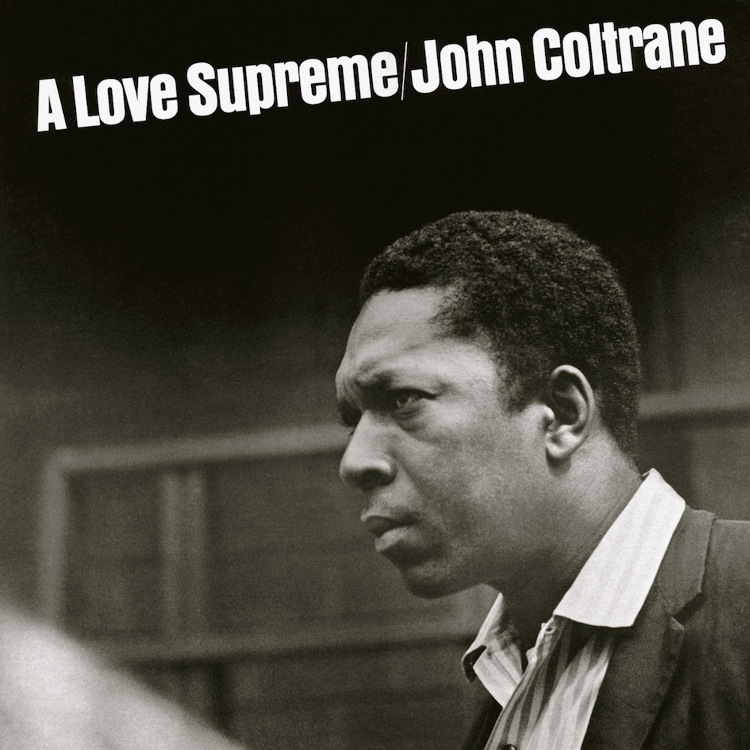

With that goal in mind, this Sunday will be Coltrane Day at Heckscher Park in downtown Huntington when the Town of Huntington, The Huntington Arts Council and The Coltrane Home in Dix Hills present a full day of music workshops, jams, concerts and an evening performance featuring Ravi Coltrane, who spent his first years as an infant growing up in his parents’ house on Candlewood Path. The event is being hailed as a celebration of the 50th anniversary of the release of the iconic album, A Love Supreme, as well as honoring the 50th anniversary of the ongoing Huntington Summer Arts Festival.

“Nothing brings people together like music, and we can’t think of a better way to celebrate this monumental work than by inviting music lovers and musicians of all ages and backgrounds to come together, listen, play and just have fun,” said Ron Stein, president of The Friends of the Coltrane Home in Dix Hills, a 501c3 tax-exempt group dedicated to restoring, interpreting and preserving the house and grounds where John and Alice Coltrane, an innovative jazz pianist and harpist, lived and raised their family. The event will also mark the launch of the Coltrane Legacy Education Project, a new music education program designed by Alice Coltrane, who died in 2007.

“One of the goals of the home was to inspire people of all ages and backgrounds to participate in the making of music,” Stein told the Press. “For her, it wasn’t about learning how incredible and influential John Coltrane was. It’s about getting people engaged in the process of making music.”

That this suburban one-and-a-half story brick home where Coltrane composed his iconic masterpiece still stands is “almost miraculous,” according to Stein. Coltrane died of liver cancer at Huntington Hospital in 1967 and was buried at Pinelawn Cemetery in Farmingdale. Alice Coltrane sold the house and moved to California in 1972. In 2003, Steven Fulgoni, a new resident to Dix Hills and an avid jazz enthusiast, was in Huntington Town Hall researching the Coltrane property when he realized that it had recently been sold to a developer who planned to raze the home and subdivide the lot.

Through his efforts, soon augmented with support from Coltrane’s family and celebrated musicians like Carlos Santana and Herbie Hancock, an alarm went out to the local community and jazz fans around the world responded. The demolition was stopped in 2004, and Huntington town bought the property for $975,000 in 2005, according to news reports, and declared the site a town park. But there were no public funds to do much more than that.

“When we discovered the house and took it over, it had been abandoned for two years,” said Stein, who gave this reporter a rare look inside, where a total gut-rehabilitation is in full swing, with walls torn out, no plumbing, and lots of gaping holes that need to be filled. “The bones of the house are actually in surprisingly good shape.”

General contractors, architects and electricians have been donating their time to the tune of almost $200,000, according to published reports. So far the nonprofit group has received $38,310 from New York and $5,000 from the National Trust, as well as thousands more from benefits in Manhattan and elsewhere. The entire project may run more than $2 million, Stein told the Press, and his group hopes to snare more matching funds from grants and donations. But first they have to come up with their own funds to match.

“We’re really gearing up to raise money in a very big way these next six months,” Stein said. “They’re going to be very important.”

In March, an architecture and historic preservation team of students from Columbia University was onsite conducting research to help the home become a living museum. The garage where Coltrane kept his Jaguar XKE—his one indulgence, Stein said—will be converted to a temporary visitors’ center. What happened to that car is unclear. At the moment, the garage is far from finished.

In the basement where the Coltranes were building a studio, the mold looked like “a coral reef,” Stein recalled when he first went down there. The hope is not only to restore the studio—the ledge where Coltrane rested his saxophone in an archival photo looks just like it once did—but make it fully functioning so new music can be recorded there again. On the first floor in the family room, the grand piano is long gone, but some of the architectural touches, like the special paneling, remain.

But more amazingly, the original purple carpets are still in the master bedroom as well as the yellow, red and orange carpeting in the large meditation room—the colors of the chakras, according to Alice Coltrane, who had become a devoted follower of Eastern philosophy and religion.

The upstairs room where Coltrane channeled the material for his breakthrough album in the summer of 1964 still has the original floral print wallpaper. But the view from the window has certainly changed, because now it’s just an acre or more of overgrown woods tangled with vines. Once the renovation is completed, it should look out over the Alice Coltrane Memorial Garden, which will have paths and flower beds.

“We’re going to make that one of the high points,” said Stein.

As Alice Coltrane recalled, one day her husband came downstairs from this upstairs room “like Moses coming down from the mountain,” holding the musical manuscript in his hands. According to Ben Ratliff, a jazz critic for The New York Times, the complete outline for this new suite was formally prepared unlike any other previous Coltrane composition, and it showed his thoughts: “Make ending attempt to reach transcendent level with orchestra…rising harmonies to a level of blissful stability…last chord to sound like final chord of Alabama.”

Then he got to work with his group of musicians until he was ready to go into the studio in Manhattan. Recorded in one day, Dec. 9, 1964, A Love Supreme is “not just another cusp in a series of cusps,” Ratliff writes, “but the fulcrum of his career, setting the outline for understanding both his past and future work.”

“Throughout his life,” writes Branford Marsalis, a jazz superstar, in his introduction to a biography John Coltrane: A Sound Supreme, “Coltrane was so engaged in the creative process that his growth as a musician closely paralleled his own personal and spiritual development. For this reason, there is an emotional depth to Coltrane’s music, an almost unearthly quality to his tone, that can leave the listener stunned, if not thoroughly seduced and moved in extraordinary ways.”

In the near future, that’s the effect the Friends of the Coltrane Home hope to recreate in the suburbs of Suffolk County.

“Look, we know when we get this house rebuilt it is part shrine, part museum,” Stein said. “Musicians who are Coltrane disciples are going to be traveling from around the world to come to this location and experience the site. And that’s why making the outside landscape as beautiful as possible is a big part of it.”

In fact, that homage has already happened.

“We discovered a musician who had hitch-hiked all the way up from Florida who was sitting outside with a saxophone playing up to the house,” Stein said. “We get that.”

The all-day music festival at Heckscher Park, 164 Main St. (aka Rt. 25A), in Huntington, kicks off on Sunday, July 5, at 11 a.m. and runs until 5 p.m. There will be music impro and percussion classes led by Shenole Latimer, Terry Greene II, Jerry Liggon and Napoleon Revels-Bey, plus workshops led by Funk Filharmonik’s saxman John Scarpulla and percussionist Steve Finkelstein; rap/hip-hop by Clifton Torres; electronic music by Mikah Feldman-Stein; and blues jams led by Willie Steel. Bangalore Breakdown, led by Premik Russell Tubbs on sax and Uli Geissendoerfer on keyboards, take the stage at 12:30 p.m. Mala Waldron, a talented vocalist and keyboardist, hits the stage with her quartet at 3 p.m. Her well-known dad, Mal Waldron, had played piano with Coltrane early on. At 7:30 p.m. the Ravi Coltrane Quartet starts its evening performance with a discussion about A Love Supreme.