Strada, village beat the state in highest court

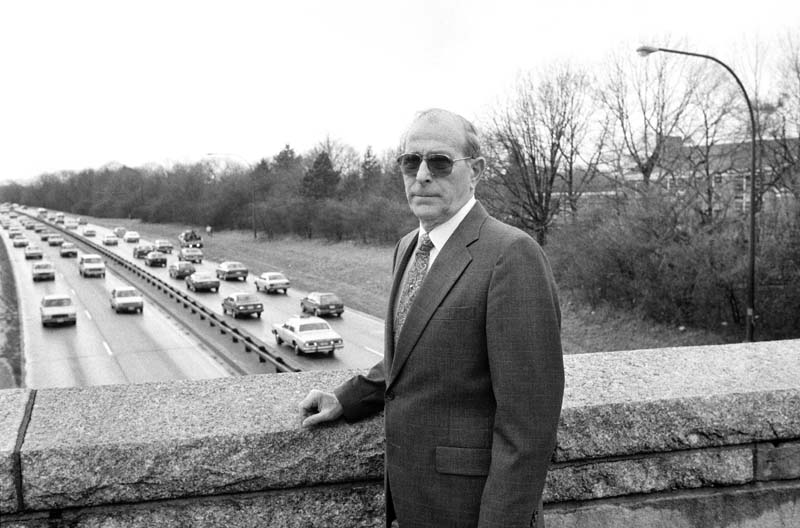

In the late 1980s, Village of Westbury Mayor Ernest Strada found himself under intense, at times unrelenting, pressure.

The unions were against him. So was the powerful Long Island Association. Politicians, even fellow Republicans, begged him to relent. Letters poured into his office urging him to change his mind.

But he stood his ground. The law was the law—and he had the village’s interests to protect.

It all centered on one of the largest infrastructure projects Long Island had seen in decades.

The intersection of the Northern Parkway and Meadowbrook Parkway at the Westbury-Carle Place border had long been recognized as inadequate and dangerous. One report noted that up to 180 accidents per year took place there.

In 1983, voters passed the $1.25 billion Rebuild New York Bond, and a portion was secured for Long Island projects. In 1986, the New York State Department of Transportation (NYSDOT) unveiled a $61 million plan to reconstruct the troublesome interchange and a further $135 million to expand the Northern State to up to four lanes in each direction from the interchange to the Wantagh State Parkway.

All of this construction took place within the borders of Westbury.

NYSDOT felt there was no need for a full environmental impact statement (EIS), even though the plan would cause disruptions on local Westbury roads, impact five schools and even called for the modification of five bridges and elimination of two overpasses (at Fulton Avenue and Hicks Lane).

All this would have caused havoc, Strada said in a recent interview at the Westbury home he has shared with his wife of 65 years, Mary Ann.

In a February 1989 newspaper article Strada said, “While we recognize the need [for the interchange reconstruction] because of the congestion in this area and the high incidence of accidents, we have no idea what might happen to our air quality or ground water supply.”

As early as February 1987, the mayor expressed concern at the lack of a comprehensive EIS that covered both the interchange and road widening. In his mind, it was a violation of the State Environmental Quality Review Act (SEQRA). The Act, according to a state website, “requires all state and local government agencies to consider environmental impacts equally with social and economic factors during discretionary decision-making. This means these agencies must assess the environmental significance of all actions they have discretion to approve, fund or directly undertake.”

“In essence, they segmented the project,” Strada said. “Instead of measuring the overall impact of the total project, they measured just what impact would occur by the portion they were building.”

Construction on the interchange began in the summer of 1987. In December, the village brought legal action against NYSDOT. In June, 1988, New York State Supreme Court Judge Albert S. Robbins ruled in favor of the state agency.

Strada dismissed this ruling as a political decision.

“After losing in the Supreme Court, the village board felt strongly, as I did, and they supported my recommendation to appeal. And of course, when we won at the appellate level, the state was pretty surprised,” Strada said.

The village challenged the ruling at the next judicial level, the Appellate Division. It sided with the village in January 1989, and ordered an environmental review covering both the interchange and the widening.

Strada gave credit to the village’s attorney in this judicial fight, Steve Gordon.

“Steve at one point in his career had helped develop the regulations for SEQRA, so he was very familiar with the intent of the law and how it could be interpreted or should have been interpreted,” Strada said. “When we engaged him, we felt comfortable that he could be successful in fighting the case.”

The ultimate victory for Strada and the village came in the state’s highest judicial body, the Court of Appeals. NYSDOT had appealed the lower court ruling, and on Dec. 19, 1989, the top judges voted 7-0 that the department was violating SEQRA.

What put Strada on the hot seat was that the Court of Appeals also halted work on the interchange pending the completion of a cumulative EIS. According to published reports, the project was about two-thirds done at the time of the injunction,

In a January 1990 profile in The New York Times, Strada called this period “very tough” and “very hectic.” The article continued, “In his sparse office, furnished with just a desk and lamp, he had been bombarded with letters, most written on corporate stationery, condemning his action and urging a quick settlement with the Transportation Department.”

In a talk at the Westbury Memorial Public Library he gave earlier this year, Strada recalled, “We stopped the project dead in its tracks. I felt a lot of pressure all around. People were out of work and it was around Christmas. I was getting calls from powerful, influential people.”

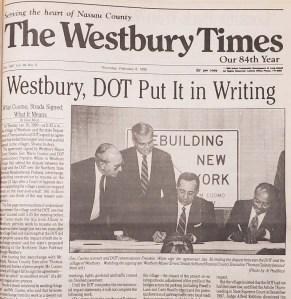

After further negotiations with the state, and the reported intervention of Governor Mario Cuomo, the two sides reached an agreement.

But while up at Albany to hammer out the final terms of the memorandum of understanding, Strada took Gordon out of the room and told him he wanted the state to pay for the legal bills incurred by the village, or he would not sign the agreement.

“They had violated their own law, and I knew how much we had spent,” Strada said, stating that he told the lawyer, “Before we settle, they’re going to have to give us every penny back.”

He continued, “When the state negotiators [were told of our demand], they were aghast.

One stood up and said, ‘If we pay that, we’ll be creating a precedent.’ Our attorney looked at him in the eye, pointed to me and said, ‘Gentlemen, this mayor is ready to set a precedent.’”

Strada showed a visitor the photocopy of a check from the state to the village for $167,751.91.

The state representatives relented and Governor Cuomo came to the Westbury Town Hall on a late January day in 1990 to sign the memorandum of agreement that would allow work to resume on the interchange.

It also gave Westbury what it wanted, according to the former mayor: “We had to get as much out of them as we could [in the agreement], having to do with things like aesthetics and the sound wall. And of course, we would not agree to the removal of the bridges,” he said. “And we got them to agree to limit widening to three lanes and not four in each direction—with no opportunity for four in the future.”

Strada had been joined at the library “Mayors’ Talk” by current Mayor Peter Cavallaro, who told the assembled, “There is a great picture at village hall of Ernie sitting besides Mario Cuomo, who had to come down from Albany to sign an agreement agreeing to modify the way {NYSDOT] was doing the project. And this was only because Ernie stood up to a very powerful governor, who some people thought was going to be president, to make sure our community was protected.”

Cavallaro added, “Among the plans, it called for eliminating the Hicks [Lane] bridge. It was preserved. And that would not have happened if Ernie hadn’t taken on a powerful governor. The lesson is that a mayor must do the best for the residents, and not curry favor with elected officials.”

“The Hicks family was very happy that we saved their bridge,” Strada said of the clan whose nursery has been a fixture in the village since the 19th century.

Asked about the governor’s mood at the signing ceremony, Strada described him as “cordial.”

He observed, “Cuomo was not happy with what we did. It had to be some sort of embarrassment for the state to be charged with being guilty of breaking their own laws, of violating the law that they promulgated.”

The two politicians later tangled when Cuomo appeared at the New York State Conference of Mayors, of which Strada was president (and in which he still represents the village). The mayor criticized the governor for passing costly mandates and leaving villages stuck paying for them without any financial support. It remains a perennial problem and a familiar lament for municipal leaders.

Recalling the governor’s reaction, Strada said, “He didn’t like me telling him ‘It’s fine for you to make the laws but we have to pay for them.’ He was a pretty arrogant guy.”

But for one day in January, 1990, the two could pose and smile for the cameras, each getting what they wanted.

Strada, in published reports, was thankful for the support shown by village residents in his time of tribulation. He remains convinced of the rightness of the cause.

“There was no way we could permit it,” he said in an interview. “[The project] was within the confines and the jurisdiction of the village. So they ultimately had to acquiesce if they wanted to get it done.”